By Nazry Bahrawi

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

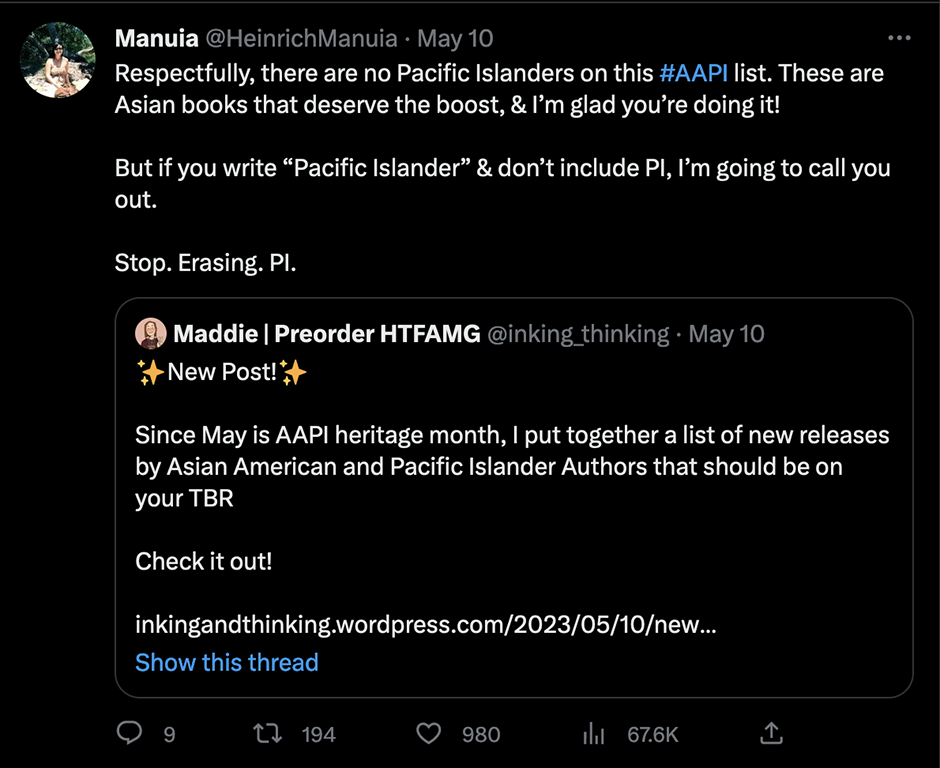

Twitter may have seen a mass exodus of critical voices protesting Elon Musk’s takeover of the platform, but if you value some of its thought-provoking, brazen takes, you might still chance upon a gem or two. This was my experience in early May as I stumbled across the tweet by researcher Manuia Heinrich Sue who holds a PhD in Pacific Studies from the Victoria University of Wellington about the Asian, Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month.

Sue’s spot-on observation speaks to the persistent problem of underrepresentation amidst increasing efforts to practice diversity, equity, and inclusion at workplaces and society in the United States. Put another way, we run the risk of glossing over certain communities despite our best intentions. For Sue, this has led her to perform a corrective measure on Twitter that draws attention to prose published by Pacific Islanders. What could be the equivalent response on AAPI underrepresentation for readers of the Northwest Asian Weekly?

Sue’s spot-on observation speaks to the persistent problem of underrepresentation amidst increasing efforts to practice diversity, equity, and inclusion at workplaces and society in the United States. Put another way, we run the risk of glossing over certain communities despite our best intentions. For Sue, this has led her to perform a corrective measure on Twitter that draws attention to prose published by Pacific Islanders. What could be the equivalent response on AAPI underrepresentation for readers of the Northwest Asian Weekly?

Words to worldviews

A good start would be to attempt to frame the issue as best as possible. Words, as some sociolinguists would tell you, have the power to shape worldviews. Superdiversity is the first term that springs to mind. Coined by the anthropologist, Steven Vertovec, this refers to the idea that multiple variables, such as nationalities and earnings, define a community alongside the traditional notion of race. It suggests that a seemingly coherent group, say, Asian Americans, can in fact be further divided into disparate sub-groups such as queer Filipino Americans, for instance.

Another relevant concept is the ultraminor. Literary scholars Bergur Rønne Morberg and David Damrosch made the nuanced point that the ultraminor must not just be defined by the relatively small size of a demographic, but also by its limited capacities and access to resources. In some American universities, students of East Asian descent are not considered ultraminor because they number more than their societal proportion—something that may have unfortunately fed into the ‘model minority’ myth of Asian Americans. This ignores the superdiversity of distinct Asian groups who live and work in the U.S.

Bearing these concepts in mind, we in Seattle can do better. Taking cue from Sue’s post, we can begin with getting to know the PI part of AAPI. A February report published by the Seattle Met Magazine lists only one such figure in their list of notable AAPI Seattleites—Joseph Kekuku, hailed as the inventor of the steel guitar. Kekuku had only made a pit stop here during the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909. Considering that King County is home to the eighth largest Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders community in the U.S., according to the Pacific Islander Association of Washington, it is surely the case that Kekuku is merely one of many notable Pacific Islanders.

We also need to take a closer look at our own super diverse Asian and Asian American categories where ultraminor communities exist. As a scholar of Southeast Asian cultures at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle, I can speak with greater confidence here by drawing your attention to two such groups.

Indonesian matters

The first are Indonesian Seattleites. Dimas Iqbal Romadhon, an Indonesian doctoral student reading anthropology at the UW, has been in Seattle for six years. Well plugged into the Indonesian groups here, he says that the diaspora migrated to the U.S. in several waves.

“There are people who moved here because of the 1965-66 anti-communist purge and 1998 anti-Chinese violence. However, most people I know are technocrats and engineers who were once employees of the Indonesian airplane manufacturing company, Industri Pesawat Terbang Nusantara, and now work for Boeing when the former was closed during the 1997 financial crisis. Most recently, the diaspora consists of the younger generation who came for the tech-industry boom in Seattle.”

Related to the first-wave migrants of the anti-communist purge, anthropologist Clark E. Cunningham pointed to two factors that facilitated it from 1965— the violence that ensued with the fall of Sukarno’s Old Order regime and legislation passed by Lyndon B. Johnson to ease the entry of Asians and other groups to the U.S. Indeed, Washington state recorded a total of 238 Indonesian individuals in the 1980 census, a number that nearly tripled to 653 in the 1990 census.

It also appears that these moves are defined by ethnicity with Indonesian Chinese forming the majority of those who migrated to flee political persecution. Meanwhile, the natives, or pribumi as they are known in Bahasa, make up the bulwark of those who came to seek greener pastures through their Boeing job switch. The fourth wave, it seems, comprises a mixture of both.

Among those who work for Boeing is Diah Darmawaty, founder of the Indonesian Diaspora Network Greater Seattle, who verified that there is indeed an Indonesian community of Boeing workers based in the northern cities of Mukilteo and Everett.

However, Darmawaty also points out that there are no Indonesian enclaves in Greater Seattle. What you might find, however, is a highly active Indonesian student association at UW that organizes the annual Keraton Festival, the largest Indonesian festival on the American West Coast. Last year saw more than 4,000 people participate in the event. You can also find a smattering of Indonesian eateries such as Indo Café on Aurora Avenue North, the roaming Bumbu Food Truck, and the now defunct Beetle Café at University Avenue.

Intriguingly, the majority-minority ethnic composition of Indonesians is reversed in the U.S. Where the pribumi account for some 95% of the population in Indonesia, they form only about 15% of the U.S. population, raising underexplored questions of why the latter had not migrated en masse—an enigma that I hope to fathom through my research. As a foil for comparison, we can look to Singapore, another Southeast Asian country. Most Singaporeans in Seattle are of Chinese descent, a feature that commensurate with the demography of their homeland.

According to the American Community Survey of 2019, there are about 2,000 Indonesians of varying ethnicities in Seattle, making our city one of the top 10 U.S. metropolitan areas with the greatest number of Indonesians.

Cham lives

Another ultraminor community deserving of greater attention are the Chams of Seattle. The Chams are an ethnic group in Cambodia and Vietnam whose members came to Seattle as refugees from the late 1970s to escape the Khmer Rouge genocide in Cambodia, as well as the Vietnam war.

In 1982, they had established the Cham Refugee Community (CRC) center in South Seattle by pooling their resources to purchase a small number of neighboring houses to build a mosque, as well as to carry out educational and social services. While no numbers have been officially reported, CRC President Asari Mohamath estimates that Seattle is home to around 2,000 individuals of Cham descent.

While they are considered stateless today, the Chams are descendants of a great kingdom known as Champa spanning the coastal areas of central and south Vietnam between the 2nd and 19th century. Sometime in the late 15th century, a war between Champa and the northern Vietnamese kingdom of Dai Viet saw the fall of some of the former’s territories, leading to a mass exodus. Some Chams immigrated westward to Cambodia as refugees while a higher number headed south to Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. A group even settled at the Chinese island of Hainan, forming a community that are today known as the Utsuls. Most Chams around the world are Muslims, though a segment of the Cham population in Vietnam are Hindus.

This superdiversity is reflected within the Cham community in Greater Seattle. Asari says that most Cham Seattleites hailed from south Vietnam, but points out that southwest Seattle is home to several Muslim Chams from central Vietnam whose members speak a different dialect. There is even a non-Muslim Cham community in Tacoma.

Contrary to the different phases of Indonesian migration into Seattle, the Chams mostly arrived in the early 1980s to escape political persecution, according to CRC Vice President Sarafine Appadolo, whose father had founded the CRC. Since then, he has not observed any major migratory waves save for occasional marriages and family members joining their kindred in Seattle. This means that the pioneer generation possesses vastly different experiences from the current generation. Is there then a generational gap?

One such gap lies in the command of the Cham language, says Appadolo. Born and raised in America, the younger generation are less proficient in their native tongue and may also hold differing views about Islam. Despite these, the Cham identity has not weakened. According to Mohamath, their sense of uniqueness as diasporic Southeast Asian Muslims with a strong history of a distinct past serves as a bridge between the generations. He adds, “The younger ones recognize the sacrifices made by the first generation.”

While close-knit, Seattle’s Chams have extended help to other refugee communities like the Rohingyas from Myanmar and the Somalis. Such relationships are fostered through the social services that they offer at CRC. Inspired by the conduct of Islam’s Prophet Muhammad to treat anyone who comes to one’s home as a special guest, Mohamath says that the Chams hope to become a societal pillar of south Seattle through their hospitality and good neighborly conduct. Indeed, Appadolo is excited to connect with more Seattleites in June through their grand event, the pasa malam (night market), celebrating all things Cham at their premises. Last year saw some 2,000 attendees and Appadolo reckons that more will join them this year.

This piece has only begun to peel the layers of the complex, sundry lives of Seattle’s ultraminorities. And so I come full circle to UW where my department, Asian Languages and Literature, is building a program on Southeast Asian cultures. At the moment, we offer language instructions in Bahasa Indonesia, Vietnamese, and most recently, Khmer as well as courses featuring literature and films produced not just by folks from the region but also their diasporic counterparts in America and elsewhere. Perhaps, sometime in the future, we could help younger Cham Seattleites master their mother tongue. For now, in the spirit of the AAPI Heritage Month, consider this an invitation for you to connect with us.

Nazry Bahrawi is assistant professor of Southeast Asian literature and culture at the University of Washington in Seattle. This is the first of a quarterly op-ed contribution by faculty, students, and affiliates from the Department of Asian Languages and Literature at UW.

Thank you for this enlightening report …