By Mahlon Meyer

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

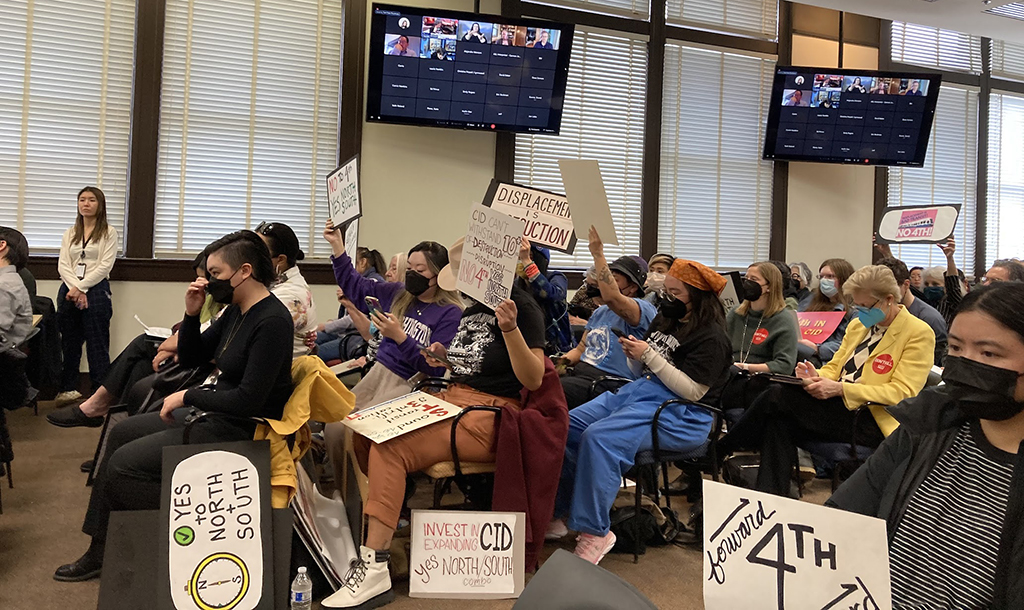

The Sound Transit board held an in-person and virtual meeting on hub station options for the CID community on March 23, 2023. (Photo by Assunta Ng)

The smell of cologne and sweat rose from the packed rows in the Sound Transit (ST) board meeting yesterday. All afternoon, it seemed, the battle raged between two sides—those for a station on Fourth Avenue and those for a station outside the community, north of the CID or north and south of the CID.

Public comments reached heights of emotionalism never seen before, from the very start.

A Cantonese speaker, who started the long string of comments going, appeared in a down coat and said he was beset by problems with his legs, so he would be unable to walk to a station not right on the rim of the neighborhood—on Fourth Avenue.

Following him, others warned of destruction, displacement, and devastation if a station was built on Fourth Avenue, including a business owner who said a decade or more of construction would bury the community forever.

But while this raged, while supporters of both sides spoke with passionate intensity, and burned with indignation or feelings of helplessness or outrage, another issue worked its way to the front.

Transparency issues

This was an issue of transparency that pervaded some of the public comments and seemed to magnify ongoing concerns of the community about responsiveness to their concerns.

During public comments, Brien Chow, chair of the outreach committee of the Chong Wa Benevolent Association and co-founder of Transit Equity for All (TEA), poured forth an overwhelming amount of figures he said he had obtained supporting Fourth Avenue. The numbers, which TEA later said were gathered with the help of Seattle Subway Foundation, included 5,153 signatures, 2,116 letters, and 1,359 letters that were directly from Chinatown.

But Chow was apparently aware that the night before the meeting, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell had come out in support of a north south option.

Speaking passionately, Chow said, “We represent over 44 businesses and organizations including family associations, tongs, and the chamber. In a democracy, it’s important to hear all the voices,” he said. “And in this case, the majority has clearly chosen the new station to be on Fourth Avenue.

But he added, “What kind of smokey backroom deal comes out of nowhere involving only the city, county, and sage?

On the other side of the room, supporters of options outside the CID waved white signs (Photo by Mahlon Meyer)

Puget Sound SAGE is a nonprofit that has been working with a longstanding activist group, the CID coalition, to promote the north south option, outside the CID.

But Chow’s concerns certainly seemed to be on the mind of Harrell, when at the close of the meeting, in summing up his decision to recommend the north south option, rather than an option on Fourth Avenue, Harrell said, pointedly, “There have been no back room deals.”

A closed-door session

This, however, was not entirely true, at least on the surface of things.

The meeting had been extended, in advance, by one hour. The usual marathon length, from 1:30 p.m. to 5 p.m., was to be extended to 6 pm. The reason given, at least by King County Executive Dow Constantine, at the outset, was to provide for “robust discussion” among board members.

But, as public comments ended, and there were still scores of people signed up to give them, Constantine made a surprise move and asked the public to vacate the Fisher Boardroom, where the meeting was being held.

After many in the audience began to rise, he seemed to reconsider, and then announced the board itself would leave the room for an “executive session,” elsewhere, that would last 30 minutes.

As Constantine stood up, an indescribable shriek went up from the rear of the boardroom that sounded like an expletive followed by “—your meeting!”

It turns out, a state law governing meetings by public bodies, entitled “the Open Meetings Act,” mandates that anyone calling an executive session must give a reason for it. Constantine’s office, queried about this issue, referred a reporter to ST. It was then relayed to his office that ST does not comment on the actions of board members. There was no further response.

The executive session lasted quite a bit longer than 30 minutes.

When the board returned, they voted, and the decision to select the north south station as the preferred alternative, while preserving further study of Fourth Avenue options, was enshrined.

Harrell: mitigating harm

In summing up his support for the north south option, Harrell was joining Constantine and Seattle City Councilmember Tammy Morales, who had earlier come out in favor of that option.

But Harrell made it personal.

As the first mayor of Asian American background, he said it was his concern for the damage that would almost certainly be wrought by a decade or more of construction overflowing into the neighborhood, which he called a gem.

“My own family has had small business in the community for 80 years and still does,” he said.

It was a statement that seemed to stand out among a long and sometimes technical discussion among board members who, at times, seemed to become bogged down in procedural matters about whether an amendment needed to be voted on first before it could be discussed.

King County Councilmember Joe McDermott, for instance, said he had been “caught off guard” at one point.

Discussion also ranged about the purported additional cost of a Fourth Avenue station, which was estimated at between $700 and $800 million.

Board members variously questioned the calculations that had arrived at this figure while others said, as a regional entity with taxpayers from outside of Seattle still waiting for the system to reach them, such a sum would never be approved.

Indeed, Constantine said he did not want to give supporters of Fourth Avenue “false hope,” even though Fourth Avenue was retained, at least as a prospect for further study.

Supporters for Fourth: mobility and transfers

Of the supporters of either side, they were more hewn to consistent points than in the past, bespeaking the maturing of coalition-building.

The seniors who support Fourth Avenue left right after they finished speaking. (Photo by Assunta Ng)

Supporters of Fourth Avenue returned again and again to the theme of having a transit hub that was closer for senior citizens and the mobility impaired. They also returned to the position that it would bring more people to the neighborhood, a point those on the other side contested, saying it would be just a “pass through.”

Finally, they talked about increased transfers and time needed to reach the airport or other parts of the city.

Supporters for north south: the dangers of construction

For those who supported the north south option, the theme was again the inevitable destruction that so many years of construction, street closures, dirt, trucks, and the unforeseen whims of contractors would bring.

They argued for the preservation of one of the last Chinatowns in the nation. And they returned again to principles of equity and the epitomization of communities of color by the CID.

When, after more than five hours, the board voted to pass the amendment selecting north south as the preferred alternative, those remaining, a cluster of young people in black t-shirts with ‘Chinatown International District’ on the back and in many cases wearing wool hats or bandanas over their heads, clapped and cheered.

The disappointed

The irony was that the single person who had, more or less, brought the dangers of ST’s planned expansion into the CID to the attention of the community was, at the end of a more than a year long process of intense organizing, researching, and advocating, disappointed by the final decision—she had wanted a transit hub on Fourth Avenue.

No one had done as much as Betty Lau, a co-founder of Transit Equity for All (TEA) to raise awareness. Lau read all 5,000 comments written into ST in the agency’s draft environmental impact ST’s fend for. She attended every initial series of meetings, with her co-founder Chow, the late Ruby Chow’s son.

Only later, as community awareness spread, did the movement start and spread—and ultimately fracture into two opposing camps.

Mahlon can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.

The new location is like putting lipstick on a pig.

I’d like to see the recording of this meeting. Where can this be found?

Could someone please share a link of the video recording of the meeting? I can’t find it.

Mayor Harrell made his remarks about deals in back rooms on his own w/o it being a response to anyone in particular. A re-watching of the recorded video will show that Brien Chow did not verbally make such a remark, but he did put it in writing in his speaking notes. He hit his one minute limit before he could read it. Therefore Chow’s unspoken remark was not why Mayor Harrell said his. I Just want to get the sequence right.

Mayor Harrell made his remarks about “backroom deals” on his own w/o it being a response to anyone in particular. A re-viewing of the recorded video will show that Brien Chow did not verbally make such a remark, but he did put it in writing in his speaking notes, but ran of time before he could say it aloud. I Just want to get the sequence right.