By Jeffrey Osborn

Northwest Asian Weekly

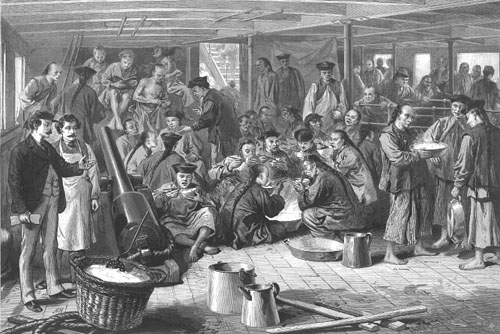

A sketch of Chinese men on board the steamship Alaska, bound for San Francisco. From "Views of Chinese,” published in Harper's Weekly on April 29, 1876. (Image from Bancroft Library)

Asian Americans haven’t always been welcome in the arena of United States politics.

As the nation has grown older, policies have changed and boundaries have shifted; and political fields have changed as well.

This has created opportunities for Asian Americans to enter the world of United States politics, but just what has the history of politics in the United States been for Asians?

Before the question can be answered, events that have shaped the Asian American population and possible politically motivating movements must be reviewed.

“Chinese, Gold Mining in California,” an illustration from the Roy D. Graves (1889-1971) pictorial collection (Image from The Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley)

1867 — With the exception of Hawaii, which wasn’t a United States territory until 1889, the first real influx of Asians to the United States was of Chinese who flooded into Northern California in an attempt to gain wealth during the California Gold Rush. By 1867, there were more than 50,000 Chinese reported as living in California. In comparison, the Census of 1860 put the population of California at a mere 379,994.

1868 — In 1868, the United States and China signed an agreement known as the Burlingame Treaty. This treaty was not only a sign of peace and friendship between the two nations, but also guaranteed Chinese the right to immigrate to America to fill the need for low-cost laborers in America.

1869 — In 1869, the 14th amendment to the Constitution ensured that every baby would be born with full American citizenship. An extremely positive sign not only for European immigrants but also Asian immigrants, as it ensured a future for their children.

The following decades would be met with political decisions that would crush the Chinese and growing Asian communities of the United States, and help shape political and social views for decades.

1878 — The first major political blow was in 1878 when a San Francisco circuit court ruled that Chinese were not eligible for naturalization, essentially ensuring that Chinese immigrants could never become citizens of the United States.

Growing unrest among California’s white working class was building. The white majority saw the influx of Chinese low cost-labor as a threat to their livelihood. Violence against Chinese in California increased, and a second major political blow was landed shortly after.

The Burlingame treaty, which was designed to inspire Chinese immigration, was modified to suspend Chinese immigration, often cutting off immigrants from their families who had intended on moving to be with their loved ones. This was because obtaining proper documentation to prove they were not arriving as laborers was very difficult. It was included in the modifications that it was the duty of the United States to retain the immigrants who had already arrived safely.

Editorial cartoon “A Skeleton in His Closet,” by L.M. Glackens, published in Puck magazine on Jan. 3, 1912. Uncle Sam holding paper “Protest against Russian exclusion of Jewish Americans” and looking in shock at Chinese skeleton labeled “American exclusion of Chinese” in closet.

1882 — The final major political assault on Chinese immigrants occurred in 1882. The Chinese Exclusion Act was passed. The act was specifically worded to prohibit “skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining.” This would not completely shut down Chinese immigration, but rather limit it to a very small number of scholars and wealthy business men. The original intent was that the act would last 10 years, allowing for tempers to calm, white miners to resume claim stakes, and for the local population to expand before allowing more Chinese into the region. The Chinese Exclusion Act stayed in effect until 1943.

1924 — Although there were small skirmishes between Caucasian and Asian communities, as well as many social injustices imposed upon Asian communities in the United States, it wasn’t until 1924 when another major Anti-Asian Act was passed. Known as the Immigration Act of 1924, it greatly reduced the number of immigrants allowed into the United States to what would be equal to 2 percent of the nation’s total population. For many East and South Asian countries, the maximum allowed was 0 percent of the United States population.

1933 — In 1933, facing similar problems similar to earlier problems of the larger Chinese population, Filipinos were ruled ineligible for citizenship. This ended up being a two pronged attack on the Filipino community, as it also barred Filipino’s from immigrating to America, severing American Filipino’s from their ancestral home.

1935 — In 1935, only two years after Filipinos were ruled ineligible for citizenship, the Tydings-McDuffle Act was passed, the primary purpose of which, from the Filipino viewpoint, was to allow the Philippines to self-govern and allow for independence of the islands. One portion of the act consisted of an agreement to consider all Filipinos aliens. This took away their legal right to work in the United States, but it was the groundwork for something that would be known as the Filipino Repatriation Act of 1935. This act allowed for free passage of Filipinos back to the Philippines funded by the United States. Upon arrival, they could re-enter the United States immigrant quota system if they wanted to return to the United States. The initial quota per year for Philippine citizens was set at 50. In 1940, the Filipino Repatriation Act of 1935 was declared unconstitutional, and the remaining Filipino’s were allowed to stay in the United States.

A young evacuee of Japanese ancestry waits with the family baggage before leaving by bus for an assembly center in the spring of 1942. (Photo from Department of the Interior, War Relocation Authority)

1941 — In 1941, the United States entered World War II after a surprise attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. These actions fed the flames of racial oppression against Japanese in the United States and led to Japanese internment camps in 1942. Restriction in the internment camps deepened Japanese resentment toward the United States government’s treatment of Japanese ancestors.

Dalip Singh Saund

1945 — After World War II, Asians began to enter the political spectrum with more than a hundred years of what many saw as unjust treatment and political abuse. The first major political office held by an Asian was that of California’s 29th Congressional District. The Congressman was Dalip Singh Saund, born in Punjab, India. He campaigned on the Democratic ticket. He also won re-election twice for the same office.

Daniel K. Inouye

1962 — Shortly after, in 1962, Daniel K. Inouye, born in Hawaii and of Japanese descent, was elected to the U.S. Senate. Inouye has won re-election eight times and continues to serve in the U.S. Senate.

1965 — In 1965, John Wing was elected mayor of Jonestown, Miss., becoming the first Chinese mayor in Mississippi.

Other acts helped to bring major changes to the political landscape in the mid- to late-20th century. An act known as the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was passed. This removed all former quotas on immigration based on nationality and instead focused on the skills and education of the applicants. This allowed for a larger number of Asians with employable skills to enter the country, rather than mostly laborers.

1974 — George R. Ariyoshi became the first Asian American governor when he was elected governor of Hawaii in 1974.

The trend continued throughout the decades with Asians filling every office, including Elaine Chao as Secretary of Labor, Gen. Eric Shinseki, the first Asian American U.S. Army Chief of Staff, and many others in every facet of government. Currently, there are dozens of Asians holding political offices in the United States.

1988 — As a sign of good will, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. This was an apology to Japanese Americans who were forced into internment camps during World War II. As a reparation to each victim, $20,000 was offered.

Political recognition is never an easy thing to obtain, and every heritage group has fought hard to be recognized in the United States and around the world. Asian Americans have earned the right to have their voice heard and as Asian political clout increases, there’s no doubt the nation will hear it.

Jeffrey Osborn can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.