By Carolyn Bick

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

Come next year, the University of Washington (UW) may no longer teach Khmer, the Cambodian language. The university is considering cutting the hard-won language program in the wake of federal funding cuts and budget shortfalls.

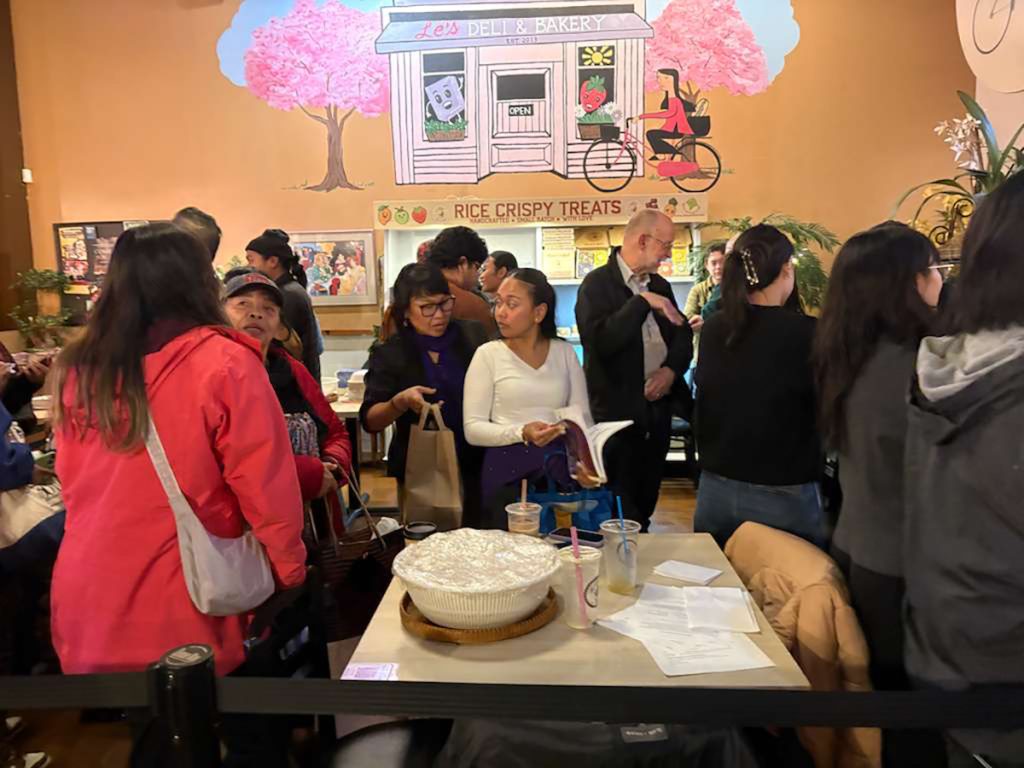

Participants at the event comprising community members, students and faculty at UW. (Courtesy of Nazry Bahwari)

But if it does, advocates say that the university would be doing itself, students, faculty, and the wider Cambodian community a grave disservice, particularly because Washington has, percentage-wise, the third-largest Cambodian American population in the entire United States.

Recently, the federal Department of Education canceled funding awards to all national resource centers, including the university’s Center for Southeast Asia & its Diasporas. The center supports students learning Khmer, Burmese, and Thai, and lost its entire $500,000 federal award, taking student fellowships and language instructors’ positions along with it.

Compounding this is the massive budget shortfall both the state and the university are facing. The UW already instituted a hiring freeze in March 2025, and many programs have frozen graduate admissions.

Now, the university is considering cutting the Khmer language program once again.

UW alumni of Cambodian descent Andrew Hollister (left) and Sambath Eat (right) officiating the event. Andrew works at the Khmer Community of Seattle-King County and Sambath at Cambodian American Community Council of Washington. (Courtesy of Nazry Bahwari)

“The fact that the UW has this program at all is due to tireless efforts from so many people,” Khmer language program alumnus Andrew Hollister said. “If it disappears, it’s not likely to come back.”

In the early 2010s, thanks to vocal advocacy led by the Khmer Students Association and the greater Cambodian community, the university started offering Khmer language courses. It only recently incorporated those courses into a formal program. The university is just one of seven throughout the country that teaches students to read, write, and speak Khmer.

This isn’t the first time the university considered cutting the program. In 2017, the UW considered eliminating the language offering, but ultimately decided against it.

Hollister was born in Cambodia to a white father and Cambodian mother. He spent his first few years of life in Cambodia, growing up with his mother’s family and learning to speak both English and Khmer. But when he and his parents moved to Seattle in 2001, his family mostly lived outside the Cambodian community and the young Hollister no longer spoke the language.

Following a second trip to Cambodia after college, Hollister discovered a desire to reconnect with the culture and relearn the language, so he could communicate with his elder relatives. He enrolled in the University of Wisconsin’s Southeast Asian Studies Summer Institute for a Khmer language intensive for two summers, before deciding to get a master’s degree in the language. After careful deliberation, he chose to study at the UW.

Two generations of Khmer language instructors at UW, retired lecturer Luoth Yin (left) and current lecturer Nielson S. Hul, at the event. (Courtesy of Nazry Bahwari)

“The real deciding factor was the Khmer language program,” Hollister said of his choice. “Out of the other schools I considered, only one other had an established, in-person Khmer language course. UW’s program had another major draw for me—the recently-retired Khmer professor Luoth Yin. He had a reputation as a respected Khmer teacher and writer for decades, including teaching my dad back in the ‘90s.”

Washington state has the country’s third-largest Cambodian population—so, said Nazry Bahrawi, an assistant professor with the Department of Asian Languages and Literature, “it should come as no surprise that the Khmer language courses have garnered strong interest from the Cambodian American community here in Seattle-Tacoma.”

Bahrawi was one of the academics at the university who successfully collaborated to find a permanent home for a Khmer language program at the UW. He said that the introductory course alone has had a steady 14–20 students for each class from 2021–2024. This is typical for languages that are less commonly taught, he said, which demonstrates a strong interest.

But beyond enrollment statistics, there are much more important reasons for the university to keep the program, said Jenna Grant. Grant is an associate professor of anthropology and the university’s expert on Cambodia, receiving a Fulbright scholarship to lecture and research from 2022–2023.

“Given that Washington state has the third-largest population of Khmer Americans in the United States, the Khmer language is part of its public mission,” Grant said. “Second, UW is poised to be a center of excellence in Khmer and Cambodian studies for the region and the country. Currently, there are only seven institutions of higher education in the U.S. where one can learn to read, write, and speak Khmer at all levels. With the federal cuts to Title VI language and area studies funding, we expect soon-retiring professors at two of these institutions will not be replaced.”

Lastly, she said, the UW has the expertise, both in its faculty and in its active Khmer Student Association and community, which has strong ties to the university.

“Having a third Southeast Asian language, in addition to Vietnamese and Indonesian, is crucial to the growth of the Southeast Asian program at the Department of Asian Languages and Literature,” Bahwari added. “It means that the department can now begin to visualize a coherent and cohesive offering such as the possible existence of a united Southeast Asian minor and major tracks.”

He also pointed out that retaining the Khmer language program would strengthen the university’s overall case for another tenure hire on mainland Southeast Asian cultural studies, noting that Cambodia leads Southeast Asia in producing critically acclaimed films.

For Hollister, the issue is multilayered—personal and individual, and broad and communal.

Though the language class was “a comparatively small” part of his experience at the university, “it shaped almost every aspect of my time there—my coursework, my research, my community involvement.”

“And, of course, with my personal stakes in learning Khmer, the program had profound impacts on me outside of academia,” Hollister said. “During my fieldwork, I gained many new friends, found a new love for the city where I was born, and spent a lot of time with my family, connecting with elders who have since passed away. None of these experiences would have been possible without the UW Khmer program and through them, I’ve forged my own relationship with Cambodia and Khmer culture.”

The program also provides a distinct tie to the wider Cambodian community and continues to strengthen cultural relationships, allowing young Cambodians to reconnect with their heritage and their elders, Hollister said. It also creates community leaders, he said.

“Many of those involved in community organizing and nonprofit work—myself included—have received Khmer language training at the UW and, in some cases, been involved with Cambodia studies in their academic training,” Hollister said. “The UW Khmer language program is in a crisis right now, alongside the country and, really, the world. With all of the funding cuts and budget crises at the federal, state, and local levels, our small program and community is at serious risk of slipping through the cracks yet again.”

Leave a Reply