By Carolyn Bick

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

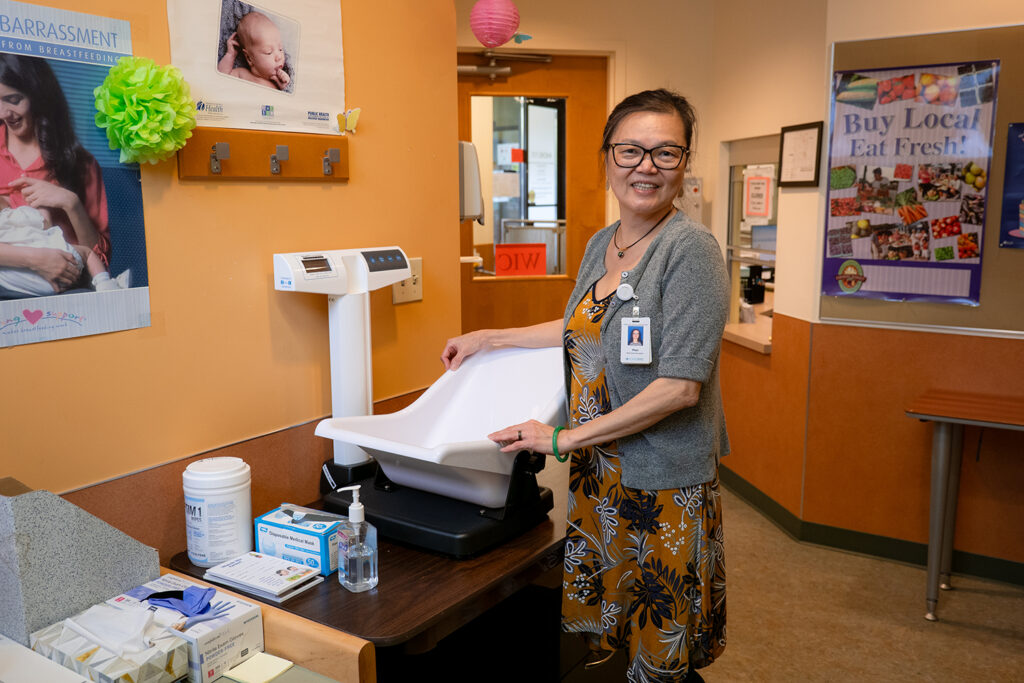

Phan Truong, Nutrition Assistant at ICHS Holly Park Medical & Dental clinic, shows the baby weighing scale in the Women, Infants & Children (WIC) office on the ground floor of ICHS’ clinic in the Othello, Seattle neighborhood. (Courtesy of ICHS)

Across the country, people who rely on the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program for food, breastfeeding support, nutrition education, and healthcare referrals are poised to lose those benefits by the end of the month, thanks to a federal shutdown that began on Oct. 1.

The program was set to expire midway through the month, if Congress still hadn’t passed funding bills that would reopen the government. At the eleventh hour, the Trump administration extended funding for the program through the end of October. The fight centers around Republicans’ refusal to remove language that would sharply cut Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act, leaving upwards of 15 million people across the country without health insurance.

On Oct. 6, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell and King County Executive Shannon announced that, through a County and City partnership with Safeway, if the federal shutdown continues and WIC benefits do run out, they would provide a one-time food and infant formula vouchers to the county’s WIC clients. These benefits will expire on Dec. 31.

But that measure is, as Braddock put it in the news release, merely a “band-aid, not a solution.” WIC recipients are hardly out of the woods.

And for King County’s thousands of Asians and Native Hawai’ian and Pacific Islanders who rely on WIC, this could spell disaster.

At International Community Health Services (ICHS), 850 patients the center serves throughout King County use WIC, and are in danger of losing benefits.

Jade East (Courtesy of ICHS)

ICHS Chief Operations Officer Jade East said that, through WIC, ICHS provides “lactation or breastfeeding support, nutrition counseling, free formula, baby foods, and EBT cards to help participants purchase eligible whole foods … that support the nutritional needs of infants, young children, and mothers.”

“Recently, due to the federal government shutdown, the WIC program stopped providing

interpretive services,” East said. “However, ICHS patients can still access care in their native language thanks to ICHS’s interpretative services contracts, and with support from our multilingual staff.”

East also said that, in an attempt to be prepared for a shutdown lasting longer than the end of the month, when WIC benefits will expire nationwide, ICHS is actively connecting with different community partners that can help WIC participants.

“At ICHS, we can still provide nutritional guidance, parenting support, and breastfeeding support at our clinical care centers and via telehealth, even if WIC is eliminated,” East explained. “However, the formula and food WIC participants count on may not be something

we can provide long-term at ICHS. … We are engaging with food banks and charities to ensure today’s WIC participants receive the nutrition they need.”

Karia Wong

Karia Wong, the family resource center director at the Chinese Information and Service Center, said that approximately 250 CISC clients rely on WIC. She said that many the center serves are worried about the increasingly unaffordable cost of food—especially if they care for young children.

“In recent years, the cost of everyday items like eggs has jumped a lot. What used to be an affordable grocery item has now become increasingly unaffordable for many families,” Wong said. “For those living on limited or unstable incomes, every dollar counts. Without the support of the WIC program, families may be forced to make difficult choices between buying nutritious food to support their children’s health or covering other essential living expenses. What once were small, routine decisions have now become a relatively more difficult call to make.”

While CISC doesn’t directly provide WIC services, it will continue to work with funders like the Washington State Department of Children, Youth, and Families and United Way to help support its clients with things like diapers, grocery cards, and gas cards.

Wong also said that the center “will continue working with government and community partners to connect families to essential needs and join in advocacy efforts to request increased support.”

“Our staff are well informed about a range of local and regional resources that can help fill gaps in food access and essential needs,” Wong said. This includes connecting people in need with local food banks, the City of Seattle’s FreshBucks program, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), also known as the Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) program. CISC also helps families use the SNAP Market Match Program to encourage them to buy fresh fruit, vegetables, and other healthy foods at farmers markets.

“Beyond food access,” Wong continued, “CISC plans to leverage resources of its early learning programs that includes the Bilingual Preschool, Child Care Health Consultation (CCHC), ParentChild+, and Universal Developmental Screening/Help Me Grow, to strengthen preventive health efforts.”

The center will continue to collaborate with service providers offering health education and referrals, and help support enrollment in health insurance plans.

Both Wong and East emphasized that running out of WIC funds means that some people quite literally will not be able to feed babies, leading to severe health complications both for babies and parents.

“Without continued breastfeeding/chestfeeding support, both babies and mothers face greater health risks, including weaker immune systems and higher susceptibility to illness,” Wong said.

The WIC program also helps prevent this by allowing people to access regular health screenings for themselves and the children they care for, Wong and East said. This reduces the likelihood of infant mortality, drives down healthcare costs in the long run, and promotes health equity, East said.

But a disruption in WIC services will also mean a delay or prevention in necessary health screenings for both children and caregivers. This means that physicians could miss certain health conditions that can have compounding negative impacts.

“If WIC funding is reduced, these preventive benefits weaken, and the healthcare system may

face a surge in avoidable medical issues, especially among infants and young children,” East said, underscoring the grave danger to children.

He also said that medical centers could see an increase in patients with conditions that are preventable via nutrition education, and that this increase would strain medical centers’ already limited resources. The loss of WIC may also mean that families may delay or forego necessary care, leading to worse health effects down the line.

“Reduced funding would not only affect the health of individuals, but also amplify public health disparities, creating a ripple effect that burdens emergency services, Medicaid, and community health programs,” East said. “In short, cutting WIC funding risks reversing progress made in maternal and child health while placing greater pressure on the healthcare system as a whole.”