By Carolyn Bick

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

As a young student, researcher and educator Jenn Nguyen both witnessed and felt the pressure of the “model minority” myth that weighed so heavily on both her and her fellow Asian and Asian American classmates. She’s carried those experiences with her ever since—and it’s part of what inspires her work as a researcher and educator.

“These pressures not only shaped academic performance in school but also impacted wellbeing, mental health, and identity,” Nguyen told the Northwest Asian Weekly. “What really motivated me was seeing how systemic inequities were showing up for [Asian and Asian American] youth with data invisibility, limited culturally sustaining support, and policies built on broad pan-Asian identities, and how these identities shape [Asian and Asian American] mental health.”

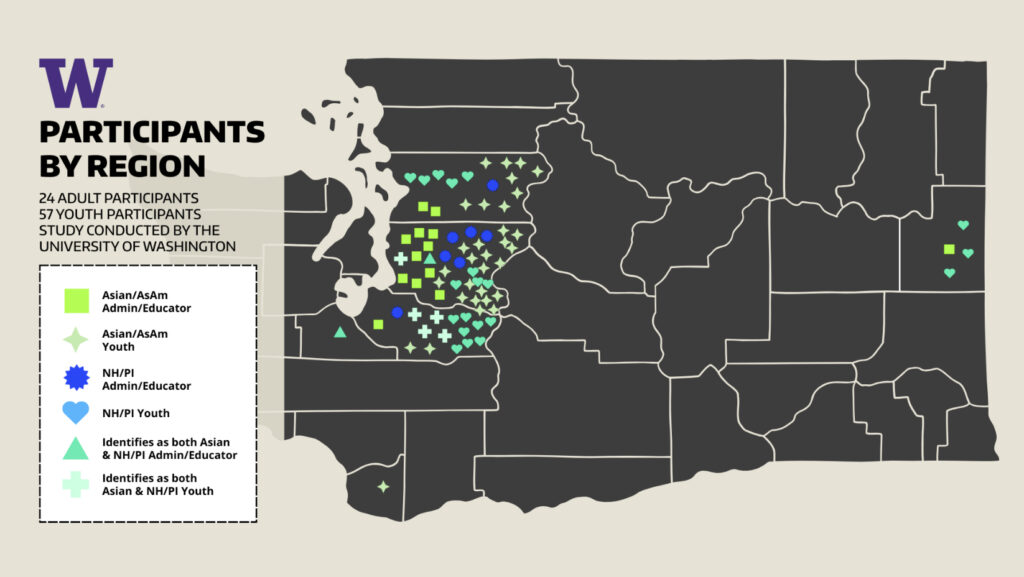

Nguyen, alongside fellow University of Washington School of Social Work researchers Max Halvorson and Santino Camacho, recently presented the fruits of a two-year study regarding Washington’s Asian and Asian American (As/AsAm) and Native Hawai’ian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) students at an Asian Pacific Directors Coalition (APDC) meeting.

The study, commissioned by the Educational Opportunity Gap Oversight and Accountability Committee, not only examined different facets of life for these students, but recognized the many differences inherent in the many cultures, races, and ethnicities so often lumped together as one monolithic mass under the AANHPI umbrella. This kind of grouping, as the researchers’ data showed, misses important variances amongst individual cultures that correspond not only to greater struggles in school, but serious mental health challenges that differ amongst different groups.

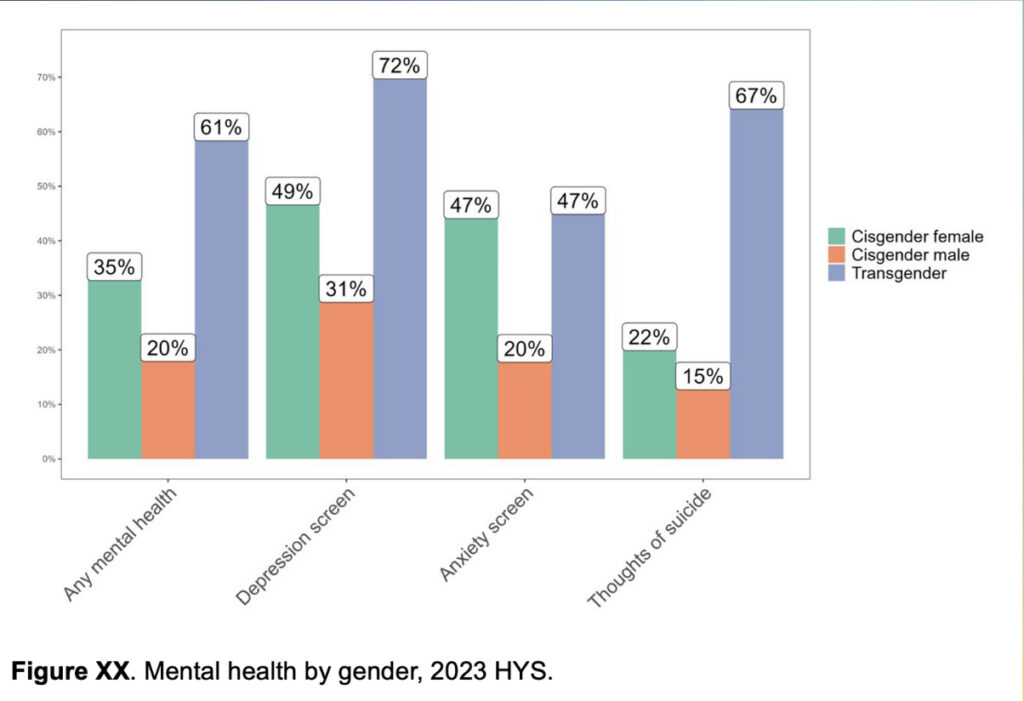

“I don’t think it’s surprising that LGBTQ+ students experience mental health challenges given bullying and a lack of acceptance across the board, but the numbers are striking, with LGBTQ+ students nearly twice as likely or more to experience anxiety, depression, and thoughts of suicide,” Halvorson told the Northwest Asian Weekly.

The researchers discovered several important, overlapping factors when it came to students’ mental wellbeing and struggles in school.

Notably, students who were part of the LGBTQ+ community—particularly transgender students from NHPI cultures, which have significantly more gender diversity than current white cultures—and those with disabilities reported both higher rates of bullying and race-based discrimination in school and alarmingly high rates of mental health challenges.

The researchers found that cultural responsiveness both supported students’ mental health and, therefore, their ability to learn. Because the researchers also looked at cultural nuance, they discovered that students from different cultures required different approaches to learning that did not either punish them for their cultures and histories or force them to choose between keeping up with schoolwork and honoring their heritage and traditions.

The researchers also found that having educators in the classroom who came from the same cultures as the students was important, and that these educators couldn’t necessarily just come from any group under the usual AANHPI umbrella.

In order to further this aim, the researchers recommended that educators and legislators recognize these differences, and build supportive frameworks that mirrored important cultural structures.

The stats

Nguyen told the Northwest Asian Weekly that she was both surprised and not surprised, when the data she, Halvorson, and Camacho collected revealed how prevalent mental health challenges were among the students they interviewed. This was true “even among students who outwardly appear to be thriving academically,” she said.

“The … data revealed that many As/AsAm students are reporting high rates of mental health changes, and there are variations when disaggregated by different ethnic groups,” she said. “This challenges the dominant narrative that academic ‘success’ equals wellbeing.”

Nguyen said that this has changed her perspective regarding how she views educational outcomes. They can’t be viewed “in isolation from mental health,” and that schools still often focus only on grade point averages “without recognizing and addressing the internalized stress and isolation that students carry.”

And the numbers don’t lie.

The researchers found that 40% of NHPI students reported feeling depressed for two weeks or more during the past year. Of these same students, just under 20% reported having suicidal thoughts. These are the highest rates amongst all racial groups.

Of these students, Chamorro, Marshallese, and what the researchers termed as “Other NHPI (combined)” students reported the highest rates of depression and suicidal ideation in this time period. NHPI students with disabilities or who were multiracial had higher rates of any mental health condition, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

Notably, suicidal ideation rates among transgender NHPI students were alarmingly high, at 67%, compared with all NHPI students (17%). Rates of depression amongst transgender NHPI students stood at 72%, double that of their cisgender NHPI student peers. NHPI girls reported more mental health problems than boys.

Amongst As/AsAm students, 26% reported feeling depressed, at some point, and 27% reported feeling anxious. They also shared separate challenges than their NHPI peers.

“I think growing up as a first-gen American and with Asian parents that don’t know English too well, and I don’t know Vietnamese that well, I think it’s kind of hard for me to communicate my emotions to my parents as a kid,” one Vietnamese student shared with researchers. “So, I think that’s kind of stuck with me. And that’s kind of why it’s hard for me to open up to people.”

Among As/AsAm students with disabilities, the rates of mental health challenges were often more than twice that of their peers without disabilities.

Like their transgender NHPI peers, transgender As/AsAm students reported alarmingly high rates of mental health challenges, including suicidal ideation (41%), depression (56%), and anxiety (47%).

Other queer-identifying As/AsAm students also reported significantly high rates of mental health challenges.

Lack of visibility

“In working with clients of color,” Halvorson told the Northwest Asian Weekly, “I have found that even when youth are able to find success in some areas, the feeling of not belonging can really weigh on them.”

Research has shown that a big part of student success and mental wellbeing is feeling as though they belong by seeing themselves reflected in every aspect of life, from the classroom to the legislature.

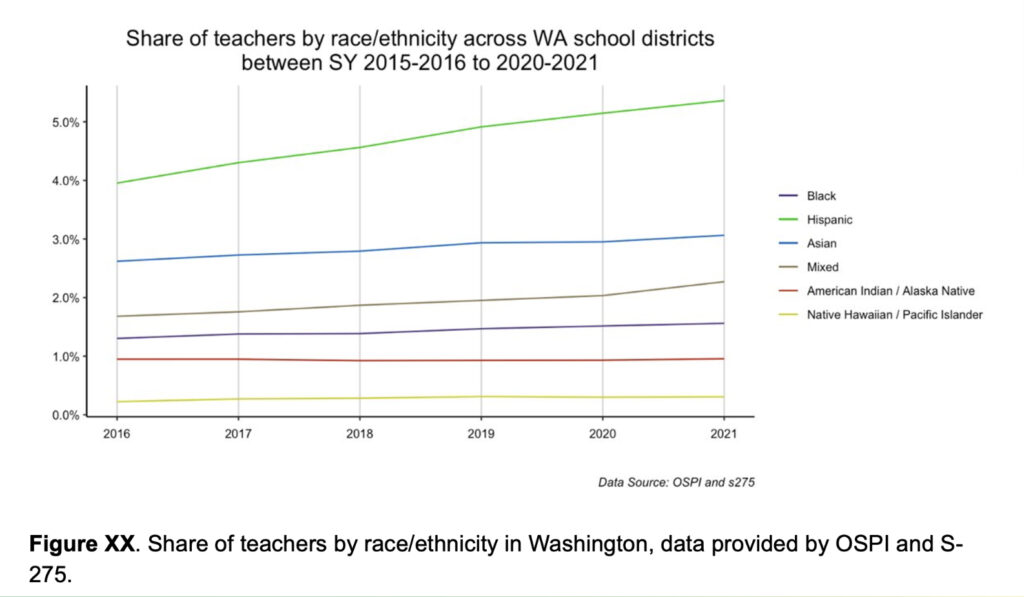

But in Washington, less than 1% of teachers identify as NHPI.

Camacho pointed out that this is often lower than the student populations of those same cultures, so “chances are, students aren’t seeing them represented to the degree that they are seeing themselves.”

“We have been teachers for thousands of years,” one NHPI educator told researchers. “We have storytelling skills, oral skills. We navigated through oceans and that’s a big one. … I really want our students to believe that about themselves, that they are capable of a wide variety of careers and skills and trade so that we can see more of them there.”

The situation for As/AsAm individuals is much the same, Nguyen shared. As/AsAm educators make up about 3% of Washington’s workforce. But this doesn’t mean that these educators are actually reflective of the As/AsAm students who are in their classrooms.

“We actually don’t know which ethnicities these Asian teachers are,” Nguyen explained. “It actually is important to also know who in our teacher workforce identifies as Asian, because, if there are schools that have predominantly Vietnamese students, but their teacher may not be Vietnamese, there might still be a ethnic disconnection that may be occurring.”

While “we really want to continue to retain and support Asian American teachers,” it’s equally important, Nguyen said, to address that students need to see educators from the same cultures as themselves, not just the same cultural umbrella.

“We really want to recruit diversity within the Asian diaspora,” Nguyen told APDC meeting attendees.

Bullying and intersectional identities

The researchers found that NHPI students had more mental health concerns, and reported being bullied at comparable rates—25%—to other students of major ethnic and racial groups. Of those who had been bullied, 24% said it was because of their race.

“I think maybe unsurprisingly, if we look at mental health and bullying data among people with these intersectional identities that we mentioned earlier, we see pretty dramatic differences,” Halvorson said, during the APDC meeting. “Students who are saying that they have some disability that they live with are much more likely to report mental health problems and bullying.”

Halvorson said that “we see pretty dramatic differences in mental health” amongst queer and transgender Pacific Islander students. For instance, compared with their cisgender peers, trans NHPI students “are experiencing by far the highest rates of mental health problems.”

“And I’ll also say that this is true if we just look at sexual identities,” Halvorson continued. “Queer, lesbian, gay, bisexual students who are not trans are also experiencing much higher rates of mental health problems.”

Camacho said that NHPI students said that they felt as though the culture and histories of every other racial group was represented in their schools, but that theirs were not.

An important part of these cultures are diverse gender identities that have their own names—but these identities are not widely understood or talked about at all in educational spaces, which exacerbates bullying and alienation. But when these students see themselves reflected in educators and cultural groups, and find their identities celebrated, the story is different, Camacho said.

“We found that QTPI (queer and trans Pacific Islander) students found belonging and support within NHPI cultural groups and with QTPI educators,” Camacho said. “These educators really helped to promote QDPI students’ overall sense of safety, wellbeing, and cultural identity development at schools—and really, at the center of this is a celebration of indigeneity … [that] helps to empower these spaces for NHPI students and also, in turn, QTPI students.”

Camacho spoke about one educator, who said that “[w]hen I hear a young Sāmoan fa‘afafine declare themselves out loud as a fa‘afafine versus non-binary or trans … it’s a cultural celebration because we’re empowering ourselves through our cultural identities.”

As/AsAm students also reported high rates of bullying, due to overlapping factors, including race, disability, and gender or sexuality.

As/AsAm students with disabilities reported a high rate of bullying and unfair treatment, too, with 51% reporting that they were treated unfairly because of their race. LGBTQ+ As/AsAm students also reported high rates of bullying, again with many reporting that they were treated unfairly because of their race.

Multiracial As/AsAm students also reported a higher prevalence of bullying than those of one race.

Indigenous frameworks to support NHPI students

Halvorson grew up in a multiracial family in Hawai’i himself. His personal experiences and struggles within the education system are why he developed an interest in education and working with young people, and decided to pursue a career in child clinical psychology.

Too often, Halvorson told the Northwest Asian Weekly, “we often address [identity development] formally, instead focusing on diagnoses and treatments.”

For instance, educators had expressed concern over NHPI students’ truancy rates. These students have an average of 36.7 unexcused absences per year, a significantly higher amount than the overall student population average of 23.8 absences per year.

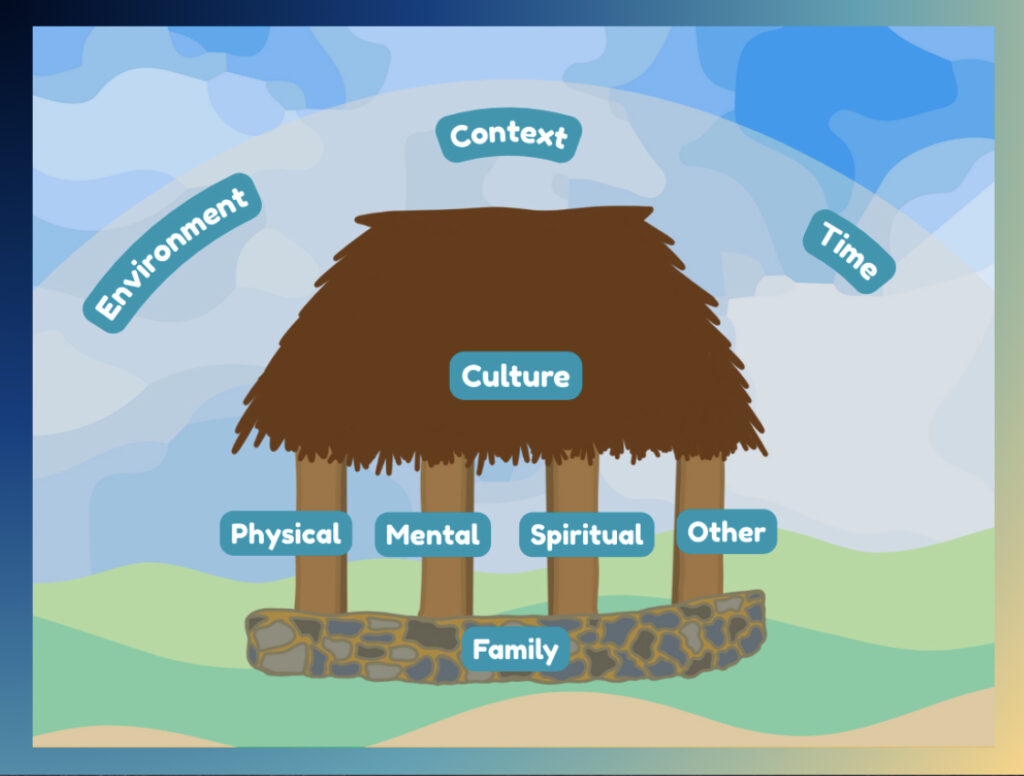

During the APDC meeting, Camacho highlighted the Indigenous Connectedness Model and the Fono Fale’ Model for Pasifika Health. The Indigenous Connectedness Model lists Relational (Well)Being as its core. From there, stem environmental, community, intergenerational, and family connectedness. The Fono Fale’ model shows a fale, or a house, with Family as its foundation. It is from these frameworks that educators and legislators can work to approach the needs of NHPI students.

Fonofale Model of Health by Fuimaono Karl Pulotu-Endemann.

During the presentation to APDC, Camacho shared a story about a student who, under the current structure of education, would be counted as truant and neglecting to focus on their studies, which is one of the stereotypes attached to NHPI students.

But this wasn’t the case, particularly when approached through the frameworks outlined above.

The student came from a Chuukese family. Someone in their immediate family had just died.

“And so when the family member died…their family was the one that hosted everybody for like a month … so they missed a lot of school during that month and then when they left, Mom kept the girls home for another three days to clean the house,” an educator told researchers. “And all the teacher is saying is, ‘Well, they don’t come to school and I emailed home and I never heard anything.’ … Well, you didn’t hear anything because they were mourning for a month.”

Camacho said that deaths, funerals, and grief periods are sacred moments in NHPI cultures. Mourning and grief periods and ceremonies can often last up to a month. But because of a combination of a lack of trust from students, a lack of understanding from teachers and in a broader cultural context, and sometimes language barriers, “there’s often conflict that arises between students and teachers.”

“We had one student even share with us that his grandma had passed away around the time that we had interviewed him,” Camacho said. “He said that he didn’t want to share it with his teacher, because he didn’t feel comfortable sharing this really private matter in his family with his teacher.”

Moreover, Camacho said, there are gaps in current school policy when it comes to culturally responsive accommodations for extended grief periods, “and from talking to educators and talking to NHPI educators who went through the school system and who are teaching in the school system now, they noted that really it’s up to the school and the principal on how to handle these cases, case by case.”

Allowing students to properly grieve and uphold their traditions around death and mourning is an integral part of caring for their mental health, and bolsters the idea of working to support these students through the Indigenous Interconnectedness Model and the Fono Fale’ model.

A sense of belonging for Asian and Asian American students

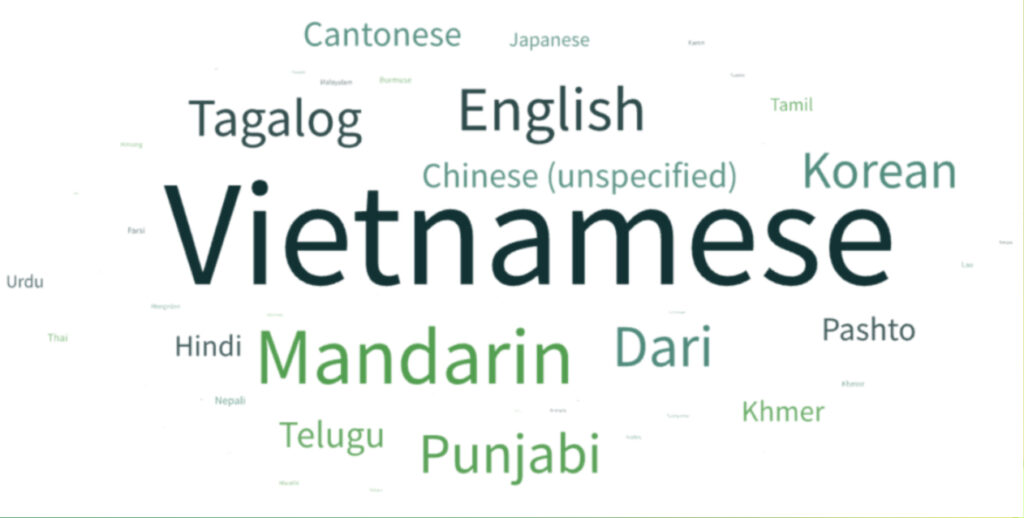

Many of Washington’s As/AsAm students are part of a diaspora spanning between 48–51 countries. But current prevailing thought groups them all under one umbrella without any cultural nuance.

This leads to things like the “model minority” myth, Nguyen explained, and furthers the assumption that all Asians and Asian Americans are a monolith, thereby erasing any cultural or historical context amongst individual peoples. These monolithic perspectives miss “unique migration tales across sub-ethnic groups that allow Asian youth to be seen.”

“When we think about identity development and cultural needs for Asian and Asian American youth, we really want to understand and understand the diaspora,” Nguyen told APDC meeting attendees. “A narrative from a Cambodian community or youth is going to be very, very different than a Chinese youth.”

Though As/AsAm students have marginally more representation within educational systems and other institutions, it’s still piecemeal, Nguyen said. For instance, in 2022, Seattle Public Schools launched a Filipinx American History class, but this doesn’t mean that Filipinx students experience culturally responsive engagement in all realms of school life.

There is also a distinct lack of access to dual language programming that would allow As/AsAm students to connect with their still-living relatives and diasporic heritage.

“Sometimes I can’t really talk to my grandparents,” one Vietnamese student told researchers. “I wish I learned more Vietnamese so I could understand what they’re saying. It’s like a part of me is missing.”

Another student shared the feeling that they don’t belong anywhere—like they weren’t “Asian enough” and they weren’t “white enough.”

“I’m Asian when people want me to be, but then I’m White when people want me to be,” the student, who is Taiwanese and white, said.

Promoting mental wellbeing

In order to combat the staggering statistics surrounding students’ mental health, researchers highlighted several steps educators and legislators can take:

- Washington public schools should continue to invest in the school mental health workforce, and particularly in recruiting and training a diverse mental health workforce that includes NHPI representation.

- Schools should provide regular opportunities for engagement between NHPI communities and school communities. Language services can make these events productive and transformative.

- Community- and educator-driven efforts to include culture in curriculum should receive support and recognition, including granting course credit via Mastery-Based Learning for participation in culturally-based educational activities.

They also noted several organizations serving NHPIs. These included the Mana Youth Program, the Marshallese Language and Culture Program in a school in Eastern Washington, and programming in Enumclaw that advanced Native American culture.

Halvorson encouraged anyone who was surprised at the team’s findings to consider the broader historical context of how Asians, Asian Americans, Native Hawai’ians, and Pacific Islanders came to become part of America.

“Colonization, annexation, separation from homelands, and refugee stories are not uncommon for many of our community members,” Halvorson said. “We believe in the ability of youth to find success despite starting under challenging circumstances; however, pretending they have no influence on student wellbeing and achievement does them a disservice.”

Nguyen agreed with Halvorson that colonization plays a big role in shaping As/AsAm and NHPI student experience. She also pointed to the importance of data that approached As/AsAm and NHPI students as belonging to individual cultures. Schools should use that data to support their students, she said, and that “there should be an emphasis on the importance of collaborating with community organizations to serve as a bridge between schools and communities.”