By Carolyn Bick

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

Courtesy of Art Love Legacies, LLC

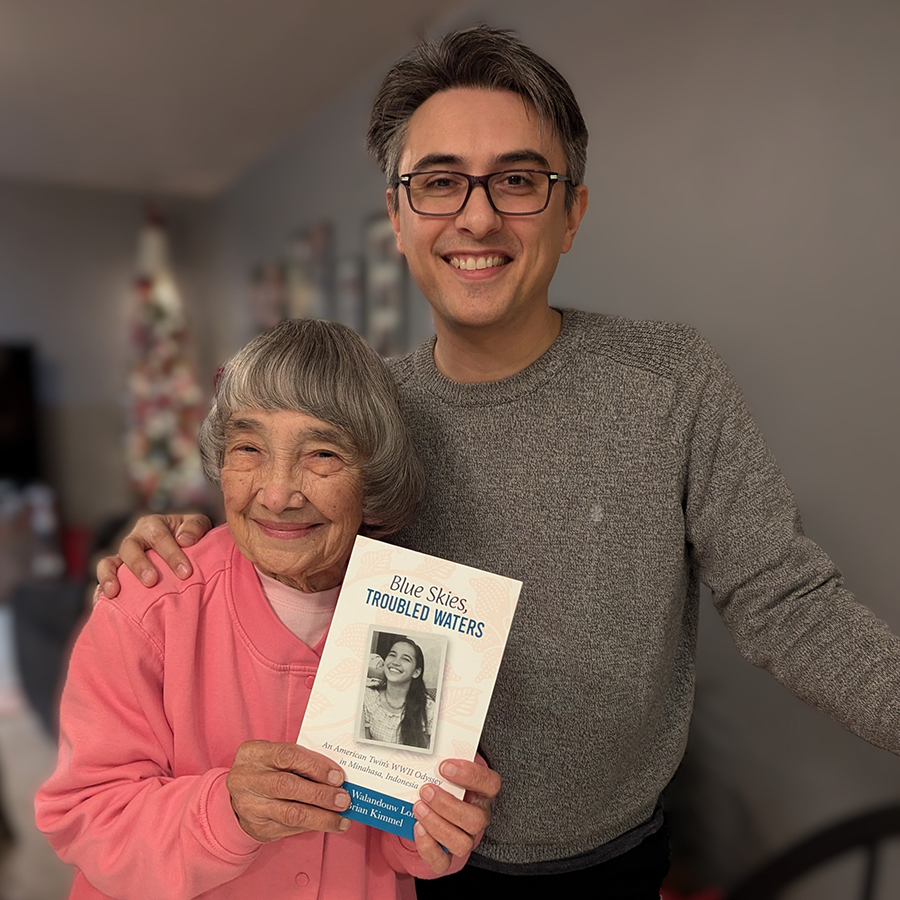

“This book is a reintroduction to this cultural historical World War Two (WWII) memoir penned by my Grandma, Martha Walandouw Lohn,” Brian Kimmel’s note to readers of “Blue Skies, Troubled Waters” begins. “Were she to meet you, she’d say, ‘Call me Grandma, too.’ That’s just who Martha Walandouw Lohn is—everybody’s Grandma.”

“Blue Skies, Troubled Waters” is the third iteration of the memoirs of Indonesian American and occupation and war survivor Martha Walandouw Lohn. Kimmel is her grandson.

Walandouw Lohn wrote the first version by hand, and, with help from her family’s friend and sponsor, published it in 1966. Years later, Walandouw Lohn shortened and rewrote the second version herself— but the third iteration was a complete surprise, a two-year-in-the-making gift from Kimmel, who presented the book to the 91-year-old Walandouw Lohn on her birthday, around Christmastime in 2024.

The book’s introduction opens with Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) agents knocking on Walandouw Lohn’s family’s door in the early hours of the morning, intent on deporting the entire family, based on her father’s lack of proper documentation—even though their mother was a naturalized citizen, and Walandouw Lohn and her twin sister were born in New Jersey. This happened in 1940, 16 years after Congress officially enacted the Immigration Act of 1924. The act included the Asian Exclusion Act and the National Origins Act, both of which severely limited immigration and entirely prevented Asian immigrants from becoming U.S. citizens.

But, given the current political climate and the federal government’s decision to target immigrants—many of them Asian, including Asian green card holders—the 1940 scene that Walandouw Lohn describes could have very well been from 2025. The scenes that follow are ones where Walandouw Lohn said she “prays to God” never happens in the United States.

Courtesy of Art Love Legacies, LLC

The Northwest Asian Weekly spoke with Walandouw Lohn and Kimmel about the newest version of the book, and why it’s such an important piece of history that speaks to these times.

Northwest Asian Weekly

You two co-authored this book, which makes it a multi-generational storytelling project, and I wanted to ask you what it was like to write it together. Did it bring you closer, and did you learn things about each other that you didn’t know before?

Martha Walandouw Lohn

Well, I wrote the other book, and Brian surprised me when he rewrote it. And I was so surprised, and it was so neat. He did it better than I did, because he could explain it better than I could.

The sentences are better. And then at the back, he explained [the Indonesian words] better, because I had a few Indonesian words in there, and I didn’t translate it—like a village, kampung. So things like that.

NWAW

This book is the third iteration of your memoir, right? What was the first one like?

Walandouw Lohn

That was written a long time ago, but it was a little bit more complicated. My sponsor helped me, and the title was, “Where Now Is My Garden.” I thought the title was wrong, too, but I didn’t want to say anything, because she was helping me. But that one was more—too much religion in it. … You still could read it, at the library in Seattle, I think, but you cannot take it out. You have to read it there.

Well, you know, it was a nice book, but everything … went like it says that “God is this” and “God is that,” and I know people don’t like to read that too much. Shirley (my sponsor) was very religious, so I had to rely on her. I didn’t dare say anything. … I didn’t want to hurt her feelings.

I was brought up very religious, we were from the Salvation Army.

I love every religion. If I see a church and I hear them singing, I will walk right in. It doesn’t matter to me, religion is, there’s only one God, so I don’t think religion has a difference with anything.

I believe in God, really, I relied on Him, that’s what kept us alive in the wartime.

NWAW

What was your second book like?

Walandouw Lohn

It’s almost the same, except a lot of things I took out. I made it shorter.

In Indonesia, where we live, on New Year’s evening, everybody goes out and they look at the blue sky. There’s a great big lake there, Lake Tondano, and in the morning, they go over there and look at the lake, and if it’s turbulent, then they say it’s a bad year.

That’s why it was titled “Blue Skies, Troubled Water.” We saw the water was troubled … and sure enough, that’s when the Japanese landed there [during WWII].

I talk a lot about the war. I don’t forget. You know, I was 9 years old, and a child doesn’t forget anything. You remember. It stays with you forever. So, Brian was a big help, and I just love the book that he wrote. I like it better than mine.

NWAW

Have you revisited your home village?

Walandouw Lohn

No. I have a twin sister, and she goes back every two years. She wanted to take me, but I couldn’t, because she didn’t see what I’d seen. She didn’t go through what I went through out there. And if I go to my farm—I couldn’t. I couldn’t go there, because I’ve seen things that bring back memories, and it hurts.

I never get over it. I still have nightmares, once in a while. But my sister lived with family up in the mountains. The Japanese didn’t take her, because she was sick. But I worked in the Japanese camp, so I’ve seen things that a child shouldn’t see.

With Brian, I could talk. You know, it’s easier, because he—I never talked with other people about it, but with Brian, I did. He’s easy to talk to and understands things, what I went through. It helps.

Courtesy of Art Love Legacies, LLC

NWAW

I understand that you also found solace in gardening.

Walandouw Lohn

Yes. I had a garden where we lived. And then when I came back, the whole garden was slashed down, and I was just screaming. And then I said, “Where is my garden?”

And then [the Japanese] had a cannon maybe about 100 feet away from my garden, and they cut down all my flowers and all my big roses and everything. They covered up the cannon with my garden. [Since then,] everywhere I go, I make a garden. … A garden is very precious to me. Flowers are precious to me.

NWAW

Do you have a favorite flower, or are roses your favorite flower?

Walandouw Lohn

The gardenia, because [during the war,] there was that little plane that flew down, and he always swooped down where I thought they could see me—so they swoop down, and I pick the gardenia, and I throw it up to him, and I always said, “This is for you. Get out of here before you get shot.”

So the gardenia became my favorite flower, and the other ones are roses. But I like every flower. I even like a weed that has a flower on. I love every flower.

NWAW

Brian, I was really curious why you chose to return the formatting to an English-language style, rather than an Indonesian one like in the second one that Martha wrote.

Brian Kimmel

When you publish a book, there are certain formatting standards that people understand, and so when you translate it to an e-book or something, it has to be in a format that works and that people will understand. So that’s the whole reasoning behind the formatting.

And nowadays in Indonesia, they also use the English-style formatting for modern trade paperbacks and other books. So the formatting is somewhat standardized, and that’s just the world we’re living in. And maybe 20 years from now, if that changes, then we could do a different kind of formatting than we would [now]. It’s mainly to have accessibility to readers.

NWAW

I also wanted to ask what it was like for you to surprise your grandma with the third iteration of her memoir.

Kimmel

Well, it was around Christmas time, and it was her 91st birthday, so just recently. We were doing all the research, and we worked with a cousin of ours and some other people. We were traveling the country, really, going to the libraries to not change the story but to back up the story with the research.

So she told the story, but then we had the pictures, and we had the documentation that would be able to verify it. And it was exactly the way she told it. So I thought that was just another way to engage with the story. To me, it was really a powerful gift.

We had some photographs, and we asked the family before gifting it to her which [book] cover might work. So it was a group project.

NWAW

When you were doing this, did you learn things about what your grandmother went through or your grandmother as a person that you didn’t really realize before that maybe hadn’t synthesized in your mind?

Kimmel

Yeah, absolutely. Not just the survival story, but also the story of her parents.

Usually, when I tell the story, it’s just a dramatic story of her father jumping ship and being deported. And just that in itself is just an amazing story, and that’s what starts the whole narrative that she wrote.

And then the piece about the Minahasin culture and the Manadonese culture that’s highlighted—you’ll see the annotated cultural context for the book and the story that highlights this particular culture in which the story is being told. And that’s also a valuable resource for people to get to know the story from the context.

NWAW

How long did this project take?

Two years.

[When I started,] I was going through a rough time in my life, and I really went to Grandma’s story in order to heal. And so it was her story of survival and our family’s story of survival that helped me in my own story. So that was really the bridge, my own healing.I don’t know that I would have discovered everything I did without going through her story. What I did was I went through every chapter, and then I wrote a response poem to each of the chapters or scenes in the book. And that’s how I made a personal connection with the story.

Because of her book, I had gone to visit the sites that are in the book, and I did go back to her childhood home. I did go to Indonesia once. It was very powerful. I cried through the whole thing. I was happy, and it was just wonderful.

And then coming home and sharing the photos with my grandma and grandpa was really wonderful. It was very healing.

NWAW

I wanted to ask you both why this book is particularly important now.

Kimmel

It’s a legacy work, and it’s a work that many people connect with. We didn’t know that immigration would be a hot topic now and that things would be occurring that highlight immigration and deportation.

It ended up to be a conversation piece, and whenever we go out and talk in the community, that’s always the topic that people want to talk about. And that occurred 70 years ago.

History repeats itself, and that’s one of the lessons of the story: If you tell the story, people in collective consciousness can remember it and recall it so that it doesn’t happen again. And I think that’s the resounding message when we talk to people, too.

Many of the people have a story about war, and that’s another thing that brings people together, is that we all have or know somebody who’s been to war or has lost someone in war or has some experience in going into the military or being a civilian during an occupation.

Walandouw Lohn

Well, it is important to—I hope, I pray to God that [what my family and I went through] will never happen in the United States. This is one story that people could read and understand what war is all about, but you cannot imagine it unless you have been in it. You have to be in it to understand what you go through and what you have to do. And I think this book is one book that they could read and think about—”What could happen? Could it happen here? Could it happen to you?”

You know, you never know.

My hardest part in the wartime was when they took my mama and papa away, I was only 10 years old. That was the hardest part.

My heart was broken. And then my happiest time was when I was able to get my mama and papa back to the United States. You have no idea.

I went crazy. It was 2 o’clock in the morning, and I got a call from my papa. And I said, “Papa, where are you?”

And he said—he turned around and asked somebody, ‘Where am I?” And they said, “SeaTac Airport.”

I said, “What, Papa?”

“We are in SeaTac Airport,” [he said.]

He didn’t say that they were coming. It was snowing. Then I woke up my husband, and I said, “Mama and Papa are at the airport.” So we got in the car, and then he was going slow. And I said, “Can’t you go any faster?”

He said, “If you get out of the car and push it, then I’ll go faster.” I’ll never forget. Oh, my God.

Oh, you have no idea how happy I was. And poor mama didn’t even have a coat on. Papa didn’t either. Good thing we had blankets in the car, so we wrapped them up and brought them home. That was my happiest day for the longest time. And they stayed with me for 12 years before they both passed away in my home.

I saw them after the war—we got together—but mama said, “I don’t ever think that we’ll be back in the United States.”

Every week, I went down to Seattle. We lived in Lynnwood. We went to Seattle, and I went and put in their name. I told the story of what we went through. This immigration man, he said, “They cannot immigrate here, but they could come on vacation.” But the thing is, we didn’t have the money then.

And then my uncle died in New Jersey, and my auntie called me. She said, “Marta, you know what? We borrowed money from your papa when you left for Indonesia.”

And I said, “How much is it?” She said, “Almost $2,000.”

I said, “Oh, dear God.” [Mama and Papa’s] ticket [to come to the United States] was $1,585. I never forgot that amount.

So she said, “I’ll send you the money.” And that’s how I got the ticket, and I sent it to Indonesia to the American embassy.

It took me two years to get them over, but I didn’t give up. I was determined to get Mama and Papa back to the United States, and that was my happiest day for my whole life.

I still think of them. I still do.

[It was] 1967 when they came back. You know, Ryan did a lot of research. He knows more than I do.……

I just pray to God that this war never happens here in the United States. That’s the only prayer that I have. Every day I think of that. I don’t think people here could take this.

I love this country. This is my country. That’s why I love the song, “God Bless America.”

There’s no country better than this country. We lived in Asia, and we lived in Holland. No, there’s no country better than here.