By Nina Huang

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

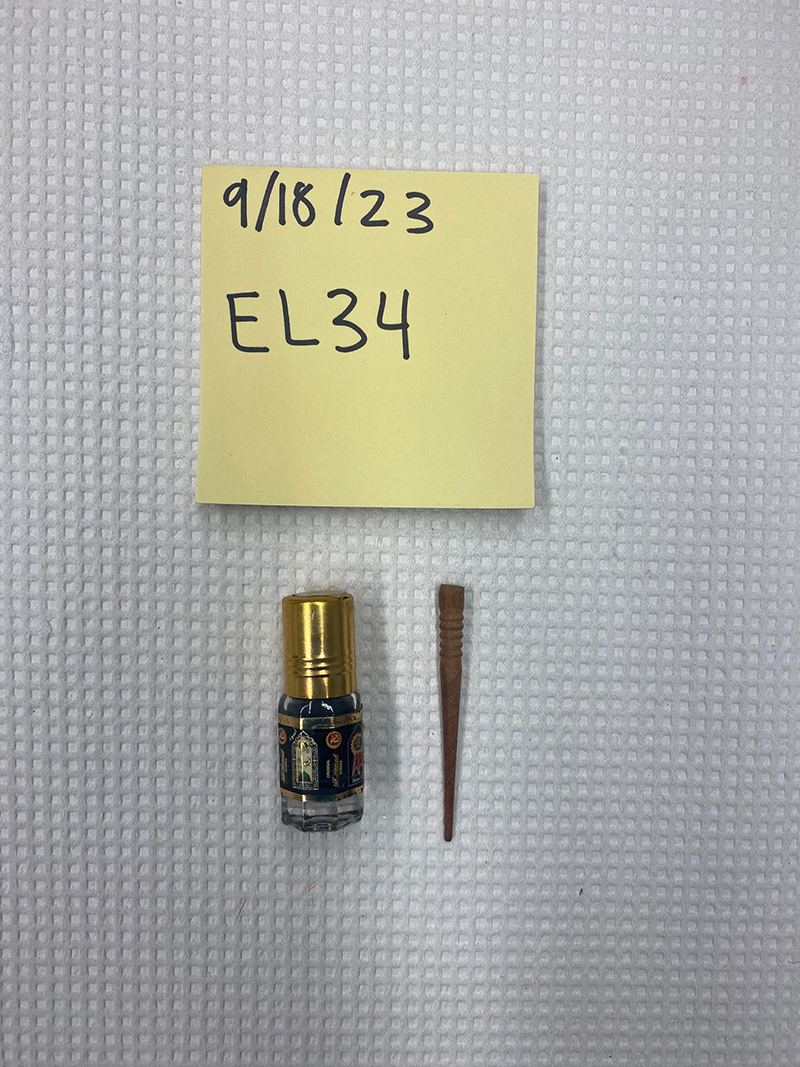

When Aesha Mokashi was a child growing up in Portland, Oregon, her grandparents would gently rim her eyes with a soft black powder—a tradition meant to protect from the evil eye.

Years later, as a graduate student at the University of Washington, Mokashi returned to that same practice—but this time as a Health & Environmental Investigator at Public Health – Seattle & King County uncovering its hidden dangers.

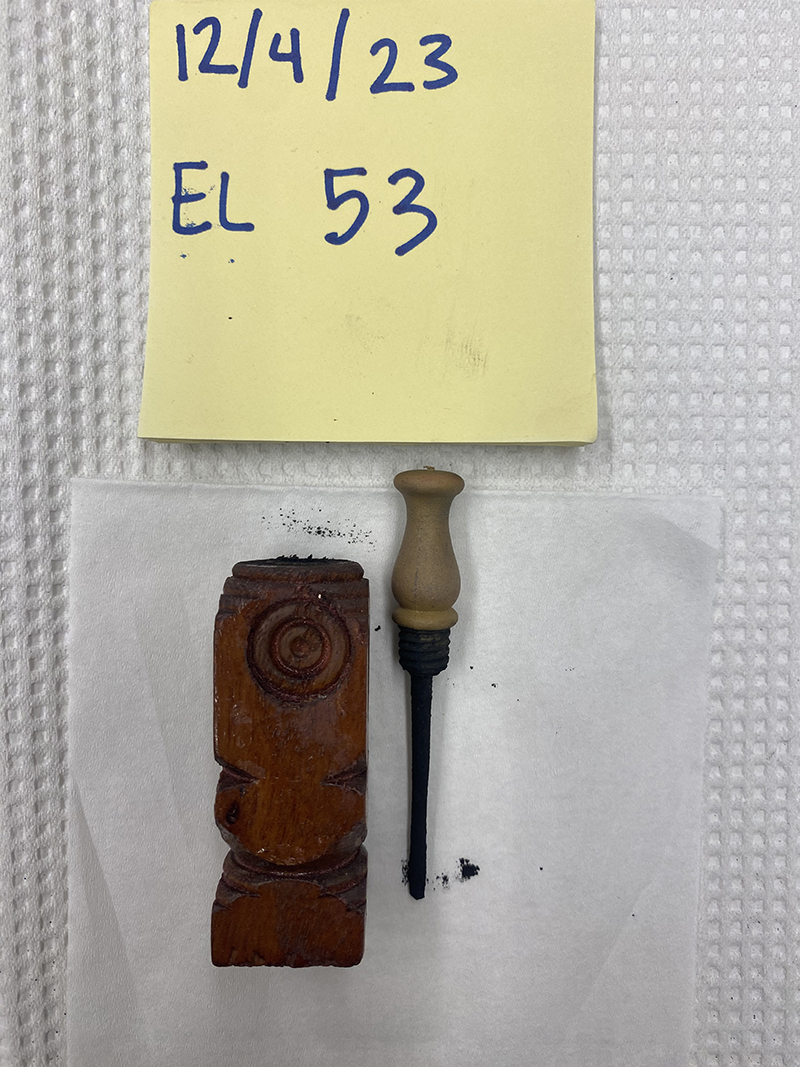

Now, Mokashi is the lead author of a recent study examining traditional eyeliners like kohl, surma, and kajal, commonly used in South Asian, Middle Eastern, and North African communities. These products, often thought to be natural and safe, can contain dangerously high levels of lead.

She has been working on this research with the Hazardous Waste Management Program in King County since she started as a graduate intern in February of 2023. Having grown up with Indian culture and traditions, this research is deeply personal for Mokashi.

“I grew up wearing traditional eyeliner and I still know people who wear these products,” she said.

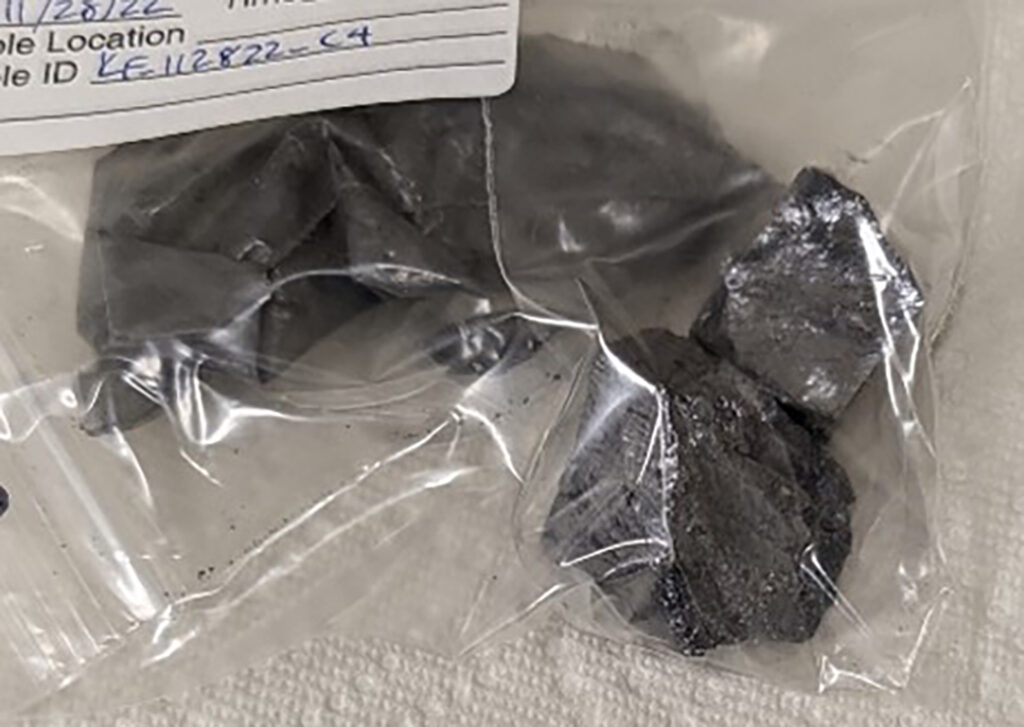

This topic was sparked by a public health mystery. Between 2018 and 2020, a wave of Afghan refugees arrived in Washington state, many of whom were found to have children with unusually high blood lead levels during routine health screenings. Mokashi’s team began investigating and discovered a pattern: families were applying traditional eyeliners to children’s eyes. Lab tests confirmed their suspicions—some samples contained up to 800 times the legal limit for lead in cosmetics.

They found that parents would apply the eyeliner to their kids and the team sent the makeup back for lab testing.

“Lead sulfide is the main culprit of why there’s so much lead in the eyeliners,” Mokashi said. “There’s this idea that because it’s from the earth, it’s safer. But lead is toxic—especially to young children.”

Working alongside Mokashi was Hena Parveen, a fellow South Asian public health practitioner, who supported the research and community engagement side of the study.

Raised in Saudi Arabia in a large Indian Muslim community, Parveen has her own deeply rooted memories of wearing kajal.

“My mom would put it on before my dad got home from work. I held on to that image,” she recalled. “After I got married, I wore it every day. It felt like a rite of passage.”

But since learning about the potential lead exposure, she’s changed her practices—and encouraged her family to do the same.

A dangerous tradition

Despite an FDA import ban on lead-based eyeliners, the products remain easily accessible in the United States. People bring them back from overseas and it’s readily available online through major retailers. Families often use them not just for beauty, but for cultural, spiritual, and even medicinal reasons. In many households, it’s common to see the eyeliner applied to children’s eyes as a way to beautify or ward off evil spirits.

Lead is a systemic toxicant. In children, it can cause neurodevelopmental delays, behavior problems, reduced IQ, and issues with bone and organ development. For pregnant women, it poses risks to both mother and fetus. Even more troubling: lead poisoning often has no symptoms.

“The only way to know is through a blood test,” Parveen said. “And by the time you’re eligible for treatment like chelation therapy, the levels are dangerously high.”

A community-led response

Rather than simply warn communities, Mokashi and her team prioritized a culturally respectful, community-led approach. They partnered with the Afghan Health Initiative, a grassroots organization run by Afghan immigrants in Washington. The group helped with everything from translation and community education to guiding families toward safer products and healthcare resources.

With the families agreeing to switch to an alternative, it led to a great collaboration between Afghan Health Initiative and King County.

“None of this work would have been possible without the support of the Afghan community,” Mokashi said.

“They helped us understand which products were being used, what they meant culturally, and how we could work together to promote safer alternatives,” she added.

Product testing events, workshops, and outreach efforts were all shaped by this partnership. Hena notes that the project was built on mutual trust.

Finding safer alternatives

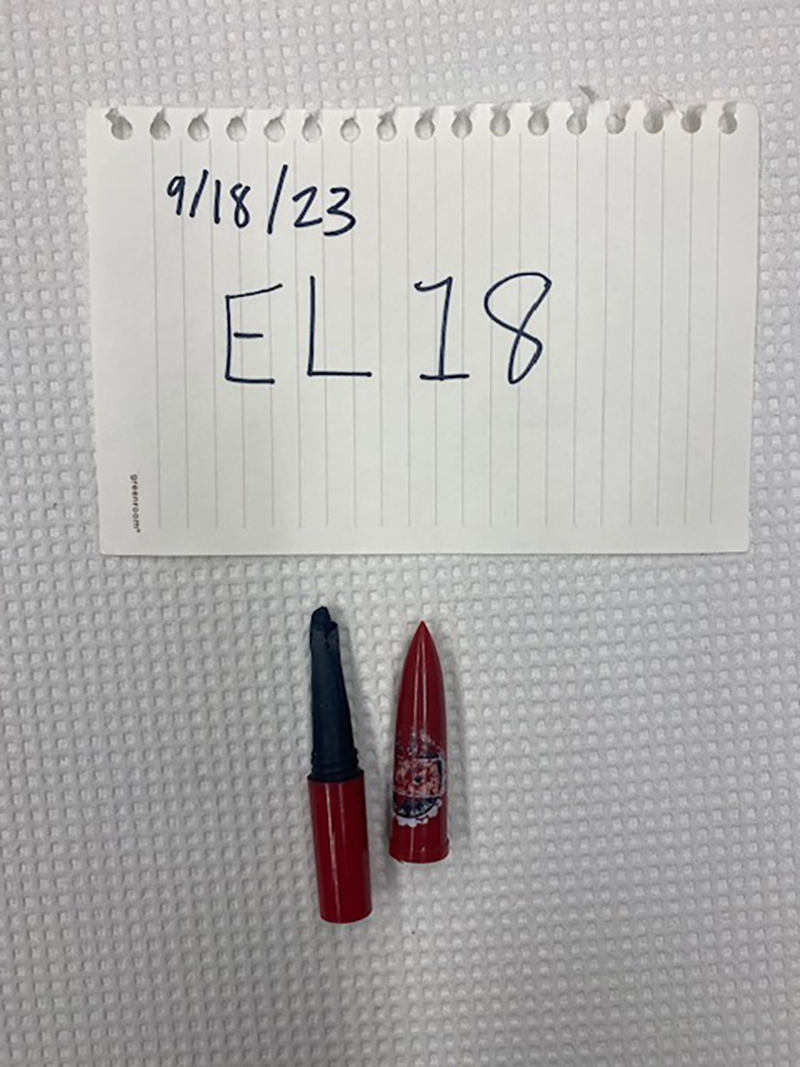

One of the key goals of the project is to offer practical, safer alternatives. Eyeliners regulated by the FDA or European Union generally contain negligible or no lead. Some families are now turning to these store-bought options, while others are rediscovering homemade methods that don’t rely on toxic ingredients.

“Back in the day, people would burn almonds and mix the soot with ghee to make eyeliner. Some traditional methods didn’t use harmful ingredients like lead, but that doesn’t always mean they’re safe. We’re here to help people understand the risks and choose safer options,” Parveen said.

For both Mokashi and Parveen, the work hits close to home—and it’s also urgent. As the team enters the next phase of their work, they’re focused on education and outreach.

“We’re developing education plans to implement next year. We want to honor people’s traditions while helping them make informed, safe choices,” she added.

To read Mokashi’s study, visit this page and to learn more about lead in eyeliner, visit this page.

Nina can be reached at newstips@nwasianweekly.com.