By Carolyn Bick

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

It’s been 10 years since Chinatown-International District (CID) activist and International District Emergency Center (IDEC) executive director Donnie Chin was shot and killed while on patrol in the CID—and for these same 10 years, the community has been asking for answers from the Seattle Police Department (SPD), which opened an investigation into Donnie’s death when it happened. Since then, there have been few updates, and no concrete answers.

SPD’s media unit sent the Northwest Asian Weekly a brief statement, stating that “[T]he investigation into the 2015 murder of Donnie Chin, a beloved Chinatown-International District community member, remains active and ongoing.”

“The Seattle Police Department Homicide Unit continues to investigate tips related to the case,” SPD continued. “Detective Rolf Norton fully reexamined the entire case last year and while no arrests have been made, the case, like all homicide cases, remains a top priority for the department.”

The Northwest Asian Weekly also reached out to several people who know Donnie personally. Though only a few were willing to go on record, those who did want to talk were eager to speak about who Donnie was as a person—friend, brother, community protector, mentor, and so much more—and the lasting impact he has had on their lives and the community at large.

Constance Chin-Magorty

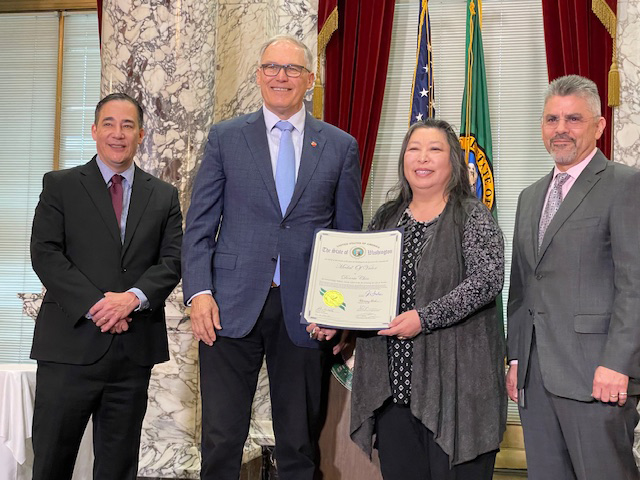

Constance Chin-Magorty (second from right) accepted the Medal of Valor award in 2024 on behalf of her late brother. Pictured with Washington State Supreme Court Justice Steven Gonzalez, Gov. Jay Inslee, and Washington Secretary of State Steve Hobbs.

Constance—who also goes by “Connie”—is Donnie’s younger sister. Chin-Magorty still runs the family store, Sun May, in Canton Alley. Ten years on, she still gets teary-eyed talking about her brother. She remembers a funny, dedicated kid who grew up to become a funny, dedicated adult, always focused on doing what was best for the community, and never once seeking the spotlight.

Growing up

He was a funny kid. We had a lot of fun. We were pretty close.

He was kind of a rough and tumble kid, so there was no way I could be a little princess, usually.

We were raised in community service. Our dad started the Chinatown Chamber of Commerce in 1963. He got the business people together to make Chinatown a better place, safer for our elders and families, and so we always helped out doing things in the community.

We have deep roots in the [CID]. We grew up in the [Central District], so just a few blocks up from Chinatown, and so we went to Bailey Gatzert grade school. We have a gift shop, which our grandfather started in 1911. So, we would walk down from grade school to the store to work at the store after school, and then kind of run the streets, get a break from working at the store, because mom would say, ‘Go and play,’ after a certain point. [Laughs]

We did work in the store, so we learned how to help people and take care of things and have responsibilities since we were little. That was just always a part of us. Dad always treated us like adults when we were little. Other people think it’s weird when I say that dad taught us to be independent, and he taught us to learn from the mistakes of others. I can remember him telling me that as a preschooler that I carried with me all these years.

He would say, ‘See what they’re doing? So you don’t need to do that, because you already know that that’s wrong,’ or ‘Look what happened to them.’

A lot of people like to learn the hard way, and we never did that because we already knew. You just see what other people do, so you don’t have to do that. That was just how we were raised. Mom taught us to be kind and to put others before ourselves, so we always knew that we were going to help people, and help them first, instead of doing something for [ourselves]. That was just normal to us.

[When IDEC started,] we would just hang out in the CID with some of the kids down there, like Dean Wong, who was [Donnie’s] best friend growing up.We would just see things happening in the community and then want to help. We would see like an elder looking through a dumpster for food, so then [Donnie] would save the little money that he had and go buy canned food to pass out [to people looking through trash cans].

[In IDEC,] I was a helper, I would say. I wasn’t into the medical thing like Donnie was, but I would help. Mainly, for the medical side, it was Donnie and Dean Wong. When we were little, you could see that people didn’t have food. So you could fix that by giving them food. As they grew older, and so did he, he could see they needed more than just food. They needed healthcare. Because if you’re sick, food might not help you. And if you’re injured, food’s not going to help you either. So, that’s why he learned first aid.IDEC and a legacy of community service

It was all just from the ground up. It’s not like they had an official training or anything back then—just learn what they (Donnie and Dean) could and teach other friends.

He would just get his friends to do it too, which is pretty funny thinking about now, because they’re still doing it. This was started in the ‘60s.

It’s just so funny. Since he was my brother, that was just normal because I did what he told me to do, because I was his sister. It’s funny that, in retrospect, people just did it.

One of the jokes is—our oldest volunteer, [Melvin], he’s 82 now, I think—after Donny was killed, there was a vigil. And the funny part was, when I was asking people about things, figuring out what to say that night, Melvin said when he volunteered, he didn’t realize that it was for life.

Because it’s true. When you sign up, and [Donnie] likes you, then you gotta come and help forever. That’s the reason you have to move away or to not come. And I’m not even kidding. You can ask any of them [in IDEC].

There was a Chinese school just a couple doors down from IDEC. Some kids grew up in the alley. When we were kids, both [their] parents usually had to work, so they would just lock the little kid in the apartment all day by themselves. But back then, it might have been what they did in order to pay the bills. So, you can see them in the window, under the window.

[Donnie] would talk to the parents and say, ‘Hey, you can bring them over here and come pick them up when you get home from work,’ and he’d watch them. When they got older, he taught them first aid, so they learned to give back to the community. He mentored generations of kids down there.A lot of the kids that started with us were mentored by Donnie. Two of the girls grew up across the alley from IDEC in a little storefront, and they both [are in the medical field] now, because they wanted to follow in his footsteps. One’s a nurse and the other one’s in medical school.

The kids are really his legacy. People ask what that is, but it’s really the kids, the teachers and counselors, all because they wanted to be like Donnie. He knew that they would do good things. There was no doubt about that.

She’s worked her way up into management things, but she was counseling and everything [with IDEC]. So he could see some of the kids already working in the community, before he passed.

IDEC wasn’t official, as far as [Donnie] was concerned—it wasn’t like a city organization or anything. People just learned who they were kind of from word of mouth. And, of course, he would make little posters and put those out.

Originally, so people could see them to know who they were to help them, [members of IDEC] would wear like these brightly colored or white jumpsuits, but with an Asian community pass on it or something. Then you can say, “Hey, there’s that guy who can help me.”

Eventually, it became the khaki uniforms that we wear now.

Medical work

I just always picture him as a blur running past carrying his first aid kit.

When we were still pretty young, he would say, “Oh, there’s a call across the street. So grab one of the bags.”

And so these bags had everything in them, because he never knew what he needed. [They were] these old suitcases that our family had and, I’m not kidding, it was like 40 pounds. And I’m 75 pounds, trying to drag this thing across the street.

It took me almost the whole time to get over there, you know, because he had one [suitcase]. I had to get the other one to help that person.

But just his dedication was really inspiring. Even as a kid, you could just see that he was truly dedicated and selfless to work for his community. It was pretty amazing, really. And when you’re a kid, that’s just normal.

This is before your stories of little kids doing great things now, which is so amazing. But this is all before like the internet—none of that existed. 911 didn’t even exist [in Seattle] back then

But they knew they could call Donnie and he would help them, because in the ‘60s, police and fire would be slow to respond. It’s an immigrant community. They don’t know if they speak English or not. [Police and fire] might come later or maybe not show up at all. And so that’s the gap that [Donnie] was filling.

It seemed that he had no desire for any sort of spotlight. He really just wanted to care, give back to the community, and help everybody else learn how to do that so that whenever he was gone, it could still keep happening. And he was funny.

Everyone knew who he was. If you didn’t know who he was, you knew that he helped your mom. He helped your friend. He helped your neighbor. He was a safe person that everybody could depend on. And they knew that.

Eventually, organizations would want to honor him, which he didn’t like. So, he would say, ‘I’m not going to come unless you make a donation.’

He would rather be working than get this award in front of people because he didn’t care about stuff like that. If they would make a donation to IDEC, so we could do more work and buy more supplies, [he would say,] “OK, I’ll come.”

He never thought it was about him. He just thought he was doing his job, taking care of the community.

He would be so surprised at people’s reaction to his passing and everything—“What are you doing? Stop doing that.”

Dr. Copass, who ran Harborview Hospital and Medic One for 35 years, was [Donnie’s] mentor. [Donnie] would hang around the Asian firefighters—there were just a few—but he would hang around them so that he could learn more.

And then he’d go up to Harborview Hospital, because that’s, you know, the main triage hospital for Washington state and see what he could just learn from being around it. Dr. Copass liked Donnie because he could see that he was but pure of heart. He was really interested in, “How can I learn to help people? What can you teach me, so that I can help more people?” And I think [Dr. Copass] liked that. He could see [Donnie’s] dedication even as a kid. Eventually they became friends.

Since Dr. Copass was Donnie’s mentor, he had Donnie train every paramedic class [beginning with] class 17, and now they’re like in the 50’s.

He would teach the class on how to work on the streets, which is entirely different from a sterile classroom environment. Or even if you do a mock trauma, you’re still out where it’s just you and it’s safe there. But on the streets, it’s different, because there’s just people walking around. Sometimes they’re in the way. Sometimes they’re dangerous. And you still have to work on that patient. So a totally different way of looking at things is what he taught them.

Donnie was really close to station 10, which is in the CID, and then station 6, which is in the Central District. And then, of course, headquarters because they all know him. When Donnie was killed, they wanted to do something to remember him. At the candlelight vigil, they came, [stations] 6 and 10 brought their fire trucks, and they did cross ladders. That’s usually only for a fallen firefighter.

Inside of station 10, they have a dragon that hangs in the big window, and that’s to represent Donnie still watching over the CID. It’s a giant thing that was actually a piece of art that was made to go outside and they’re all over the CID on telephone poles.

This one is more of a corkscrew, and he was made to go around a specific pole down by where Uwajimaya used to be, but in between the time it was designed and the time they were going to install it on the pole, there were way too many wires. You could not get [the dragon] on there, so he was just like a spare in storage.

So, he was available. The fire department wanted him for their big display windows, so the city came together, and the designer was still in town. He wanted to be a part of it and help make sure the dragon was all intact and help them install him in the fire department.

They also have a plaque inside the fire department. They make them for fallen firefighters. They made one for Donny. It was also an informational plaque to tell his little story. All that’s in station 10.

[Donnie] was like this little ghost that would just magically appear. That’s always the joke with the fire department. They were like, “How did he get there so fast?”They’d be in a truck or a car driving to [an emergency scene] from just a couple blocks away, yet Donnie was always there first. No matter where it was. And he still had to carry everything by hand because he never would drive a car or anything and go to the incident. He would just run, carrying his pack of stuff. That’s what he did all day—just ran around with a 40-pound suitcase.

Eventually he became more streamlined, because when you hear the call, then you know what kind of incident it is, and you know what to bring.

Remembering Donnie

Where other people would do it because it’s interesting or sounded like fun, they’re not going to stay in the CID to help after that.

He was funny without trying to be, which is one of my favorite things. He would just crack everybody up all the time and he didn’t even know he was funny.

He liked to try different kinds of foods—something that’s really different. If I would travel, I would always find something really different-tasting or-sounding for him to try.

When we were kids, one of our favorite things was having a float, because you can get it for not very much. A couple doors down [from where we grew up] was a soda fountain. And normally you would get, like, a coke and a vanilla ice cream. A typical float. But he would have an orange drink and chocolate ice cream, which is so disgusting to me!

But that was just him. His way of being playful was getting some weird flavor. So, I would go around the world and just bring back something weird that I think he might like.

He collected Coke memorabilia. He would ask his friends to bring back Coke bottles from around the world. We still have a collection in the store today.

He loved photography. When we were young, we always had a little brownie camera on us. This was way before cell phones existed, so we always had a camera.

He always took pictures of things in the CID or the kids. A lot of the kids that grew up in the CID—we didn’t have much. They had less. And sometimes the only childhood pictures they had were the ones that Donnie took of them. So those are really, really special. He was really more like a surrogate dad or big brother to them. He wasn’t just some guy. He was really a big part of their lives.

They all are still our family. Our IDEC members are still our family. And some of the kids that Donnie mentored have kids of their own. It’s the next generation. Most of them are pretty little. One of the older kids, his son is in [IDEC], which is really nice—father and son. That’s really nice.

IDEC, the community response and care organization Donnie started, still remains active in the community. Community members who are interested in joining may contact IDEC board member Jamie Lee at jgmlee@gmail.com.

“Liberty and Justice” is imprinted on the shields (badges) Donnie issued to IDEC officers. The courage, intelligence, compassion and humor DC brought to the C/ID community, and His impact on both SFD and SPD as a subject matter expert on urban community response are added tributes to His legacy and are a lasting influence for generations to follow.

Thanks to the NW Asian Weekly for this nice story on Donnie. Hard to believe it has already been 10 years, but the loss in the community is still felt by so many. I am happy to see that volunteers with IDEC are still visible at so many community events and functions. A shout out to them for continuing Donnie’s legacy.

Tim O