By James Tabafunda

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

About 100 people gathered at the public rally on June 19, 2025 for Tuan Thanh Phan. (Photo by James Tabafunda)

More than 100 community members, immigrant rights advocates, and legal experts gathered outside the Henry M. Jackson Federal Building in downtown Seattle to demand justice for Tuan Thanh Phan, a longtime Washington resident whose recent deportation by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has sparked outrage and ignited a statewide movement. The June 18 rally, part of the #BringTuanHome campaign, called for immediate action from Gov. Bob Ferguson and the end of what advocates describe as unlawful “third country” deportations.

A routine deportation redirected

Phan, 43, arrived in the United States from Vietnam in 1991 at age 9, fleeing post-war instability with his family and becoming a legal resident. In 2000, at 18, he was convicted of first-degree murder and second-degree assault after a plea deal he accepted, unaware of the immigration consequences. He served a 25-year sentence in Washington state prisons, during which his legal status was revoked in 2009, resulting in a valid deportation order.

Upon his release from the Washington Department of Corrections (DOC) in March 2025, he was immediately transferred to ICE custody, as allowed under state law. His family, aware of the deportation order, spent months preparing for his return to Vietnam, coordinating with relatives for his arrival at the airport.

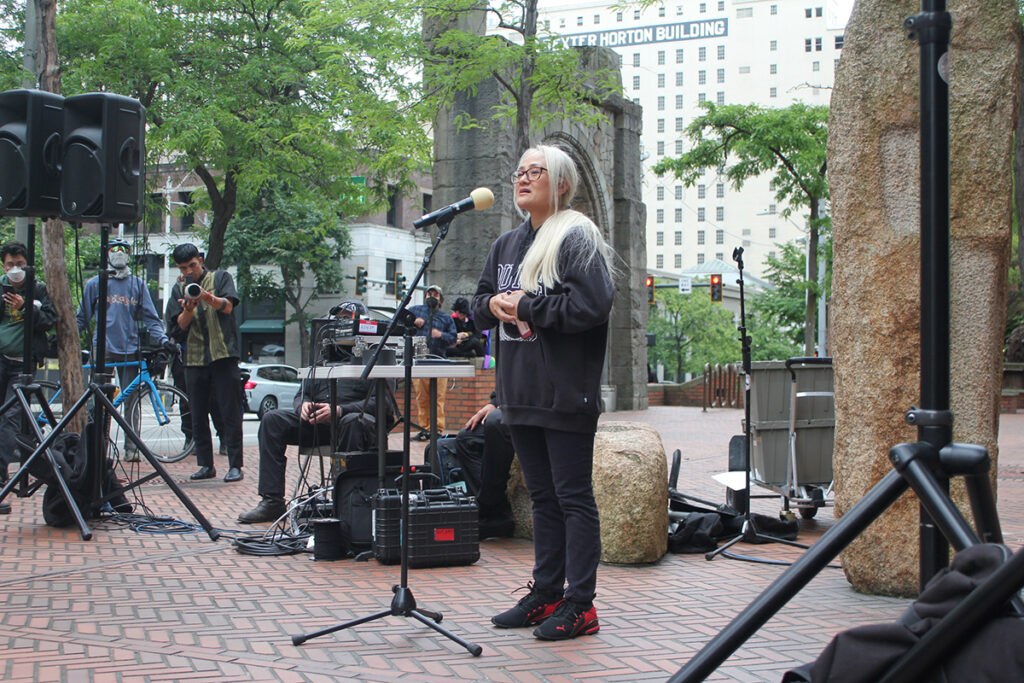

Ngoc Phan told the crowd about her unending ordeal concerning her husband Tuan Thanh Phan. (Photo by James Tabafunda)

“We accepted it. We planned for it, and we were looking forward to it,” said his wife, Ngoc Phan, in a National Public Radio interview on June 1.

Instead, ICE officials informed Tuan Phan and several others that, instead of their home countries, they would be deported to South Sudan—a country none of them had any connection or had ever lived in.

Ngoc Phan criticized the Trump administration’s decision to deport her husband to a country in the midst of an escalating civil war, where the U.S. State Department maintains a Level 4 “Do Not Travel” advisory due to ongoing armed conflict, high kidnapping threats, and pervasive violent crime.

The deportation flight was later diverted to Djibouti, a small nation in the Horn of Africa, where Tuan Phan and seven other men are detained at a U.S. military base. Their immediate future remains unclear as legal proceedings continue.

Political and legal issues

Phan’s case is not isolated. He was one of at least eight men—citizens of Vietnam, Burma, Laos, Mexico, and Cuba—placed on a chartered deportation flight to South Sudan on May 20, as part of the Trump administration’s plan to remove noncitizens with criminal records to “third countries” when their home countries refuse to accept them.

Vietnam, like several other countries, has historically been reluctant to accept deportees, especially those who arrived in the U.S. before 1995. While a 2020 agreement was designed to streamline the process for returning individuals with deportation orders, advocates and legal experts say implementation continues to be inconsistent.

ICE maintains that these removals are necessary for public safety.

“We are removing these convicted criminals from American soil so they can never hurt another American victim,” said Department of Homeland Security Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin in a May press release.

However, immigration attorneys and advocates argue that the government’s actions violate federal court orders and due process protections. In April, U.S. District Judge Brian Murphy in Massachusetts issued an injunction requiring that migrants facing deportation to third countries be given notice and a meaningful opportunity to contest their removal, including a credible fear interview to assess potential risks of persecution or torture. The administration’s fast deportations, Murphy ruled, “unquestionably” violated his order.

Following legal challenges, the Supreme Court is now weighing whether the Trump administration can continue these deportations without further process. In the meantime, Phan and the other men remain in legal limbo in Djibouti.

Washington’s role and the “prison-to-ICE pipeline”

Washington state’s 2019 “Keep Washington Working Act” restricts most state and local collaboration with federal immigration enforcement, making the state a so-called “sanctuary” jurisdiction. However, the law includes a stipulation for the DOC, allowing it to notify ICE of release dates for noncitizens with deportation orders. This exception has become a heated issue for activists, who argue it perpetuates a “prison-to-ICE pipeline” that disproportionately affects immigrants of color.

Ferguson has faced increasing calls to end DOC’s cooperation with ICE. In January, he signed an executive order creating a rapid response team to support children separated from parents by deportation, acknowledging the destabilizing effects of mass removals on families. But activists say he needs to take more decisive action.

The #BringTuanHome campaign’s demands include:

- Direct intervention by Ferguson to secure Phan’s safe return.

- An immediate moratorium on all DOC-to-ICE transfers.

- The use of executive clemency to pardon Phan and other noncitizens facing deportation for decades-old convictions.

Voices from the rally

“This is a trying time for all of us. And I really appreciate everyone being here, just giving us the love and support that we need.”

“I don’t know how to feel because lately I’ve been watching the news, and I see people just being picked up from the streets, being detained because of the way they look. I see people being arrested at their job site when they’re just trying to make a living for their families. I see people being arrested and detained for going through the legal process,” she said. “They’re being arrested at courthouses, at immigration interviews, and they claim it’s to make America safe.” Phan also highlighted the broader implications for immigrant communities.

“If they are allowed to remove people to a third country, a country that’s actually in the middle of a civil war … what does that mean for us? They’re trying to actively dismantle the rule of law in this country,” she said. “If we do not do that and they’re able to get away with this, you and I could be next.”

Musa Abdul-Fateen, executive director of the Seattle Clemency Project and a longtime friend of Phan, spoke about their shared experiences in prison and the power of redemption.

“If redemption is real, if we truly believe in second chances, then why is Tuan Phan now shackled in a shipping container on the other side of the world?” he asked. Abdul-Fateen, himself formerly incarcerated, contrasted his own post-release opportunities with Phan’s continued punishment, attributing the difference to race and immigration status.

“Since my release, I’ve had the privilege of building a beautiful life with my loved ones and serving as the head of one of Washington’s most influential legal aid organizations. I now meet regularly with judges, lawmakers, and philanthropists, all in service of making a living amends to my victims in the communities I harmed. I’m no longer viewed merely as a violent offender. Most people I work with would never imagine.”

Abdul-Fateen said, “So I ask again, what do we really believe about redemption? Is it a principle we extend to all people, regardless of where they were born or the color of their skin? Or is it a privilege reserved for those of us whose families arrived here early enough to be woven into the fabric of belonging?”

“Tuan Phan is not a threat. He’s a man who has paid his debt, who has transformed, who’s brought life and light and laughter into one of the darkest places imaginable. If we cannot find room for him in our vision of justice, then perhaps it is not justice we are practicing, but something far more selective and far crueler.”

Community demands and political fallout

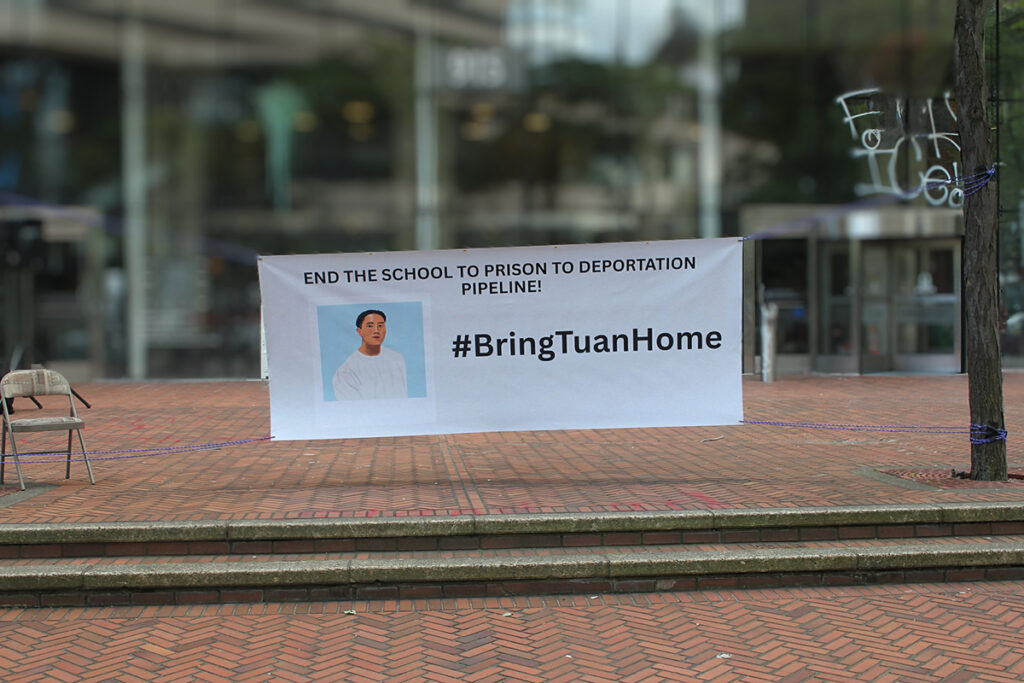

#BringTuanHome banner at the public rally on June 19, 2025 for Tuan Thanh Phan. (Photo by James Tabafunda)

The rally in Seattle is part of a broader movement, with hashtags like #BringTuanHome, #FelonsAreFamily, and #MoratoriumNow gaining traction statewide. Organizers have collected more than 700 letters and signatures urging Governor Ferguson to halt DOC-to-ICE transfers and use his clemency powers to prevent further deportations.

“Governor Ferguson really needs to take action because if we did not cooperate with ICE, this would not even be an issue,” Ngoc Phan told the crowd. “We have folks that finished their prison sentence, and then they’re handed over to ICE to be deported. That is not justice. That is not fair.”

A family in limbo

For Ngoc Phan and her family, the uncertainty continues to be the worst possible ordeal. She has not heard from her husband since his transfer to Djibouti, and fears for his safety in a region plagued by instability.

“It’s just so outrageous that I’m scared. But at the same time, it’s like, you don’t want to believe it, because, legally, how can they do that?” she said.

“So now we’re waiting to see what the Supreme Court’s going to rule. If the Supreme Court goes with this, we are in trouble. We no longer have the rule of law in this country.”