By Carolyn Bick

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been around for a while—since the early days of home computers, in fact—but only recently has the technology evolved enough to become a familiar mainstay of the casual netizen’s life.

Readers may be familiar with one of the first widespread iterations of AI, ChatGPT, a chatbot that the AI research organization OpenAI developed and launched in late 2022. By early 2023, the chatbot had gained millions of online users, but it swiftly became one of several options and kinds of AI available to generate content.

Since AI’s emergence into popular consciousness, concerns have swiftly arisen around the use and very existence of content-generating AI. These issues range from privacy concerns, unchecked inaccuracies, and AI being allowed to make hiring decisions, to security concerns and plagiarism of both artwork and writing.

Among these concerns is also the issue of AI perpetuating and reinforcing stereotypes of and biases against people who are not white, specifically against those people who are not white men. This bias emerges in a variety of ways, including in how AI “thinks” that people of certain backgrounds, such as Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) heritage, look.

Sourojit Ghosh, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Washington, broadly focuses on questions of harm and bias in large systems that are moderated by AI. He recently completed a study with UW Assistant Professor Aylin Caliskan—whose work specifically focuses on, among other related areas, AI bias, but whom the Northwest Asian Weekly was unable to reach before publication—into how one of the most popular text-to-image AI generators, Stable Diffusion, presents users with images of Indigenous Oceanians (the countries of Australia, Papua New Guinea, and New Zealand). Ghosh is currently researching how AI treats individuals of AAPI heritage. In this specific case of image generation, Ghosh had been examining what AI defines as “default person.”

“So we were looking at it and saying that if you give it no other information, what does stable diffusion think a person looks like? Specifically, what does it think a person’s gender is the default gender for a person should be? What does it think in terms of nationality?” Ghosh explained of the research process for the study regarding Indigenous Oceanians. “And the broad, overarching finding was that the results skewed male, skewed Western … light skinned faces. And there was a near-to-total erasure of non-binary identities and Indigenous identities.”

Ghosh also said that he and his fellow researchers found that there was an overt “sexualization of women of color, specifically, Latin American women of color. … And then some from Egypt, as well, were overly sexualized to a point where the generator itself was blurring out and censoring, saying, ’These are not safe for work for me to even show you.’”

While Ghosh was not able to talk in-depth about his in-progress research work regarding AAPI, he did touch broadly on what he has been finding.

“So far, the … phrase ’AAPI’ is associated with … traditional headgear, and face paint,” Ghosh said. “The stereotype very much is that an AAPI person doesn’t wear a T-shirt and jeans—they wake up every day and put on their headgear and their face paint and all of that.”

Ghosh explained that while his own understanding of what decisions the AI generator is making when depicting different Indigenous cultures is imperfect, given his limited knowledge of the wide range of Indigenous cultures in the U.S., his “gut feeling is that across the images I’m seeing, it’s pretty much one culture.”

“Short of putting it on the internet and asking somebody, I don’t know how to identify which one it is. But very much the images are just one. It is one tribal representation that has been captured,” Ghosh said.

Ghosh also sent the Northwest Asian Weekly some images based on basic text prompts the publication provided for AI image generation. The images appeared to line up with what Ghosh had said.

The issues Ghosh has been finding are not unique, and have expressed themselves even before AI image generation became popular. Large search engines, like Google, use AI to judge which images to show users who search for them—and in 2015, Google itself was taken to task for the issue. UW researchers found that Google’s image search engine mainly spit back images of white men in high-powered roles like “CEO.”

The issues Ghosh has been finding are not unique, and have expressed themselves even before AI image generation became popular. Large search engines, like Google, use AI to judge which images to show users who search for them—and in 2015, Google itself was taken to task for the issue. UW researchers found that Google’s image search engine mainly spit back images of white men in high-powered roles like “CEO.”

But it appears that Google only fixed the issue on the surface. UW Professor Dr. Chirag Shah was part of a 2022 study that looked into whether Google had addressed the problem in-depth, as part of his overall work in the field of AI. His work involves the building and study of intelligent access systems, and he is, among other roles, the founding co-director of the UW’s RAISE, Responsibility in AI Systems & Experiences.

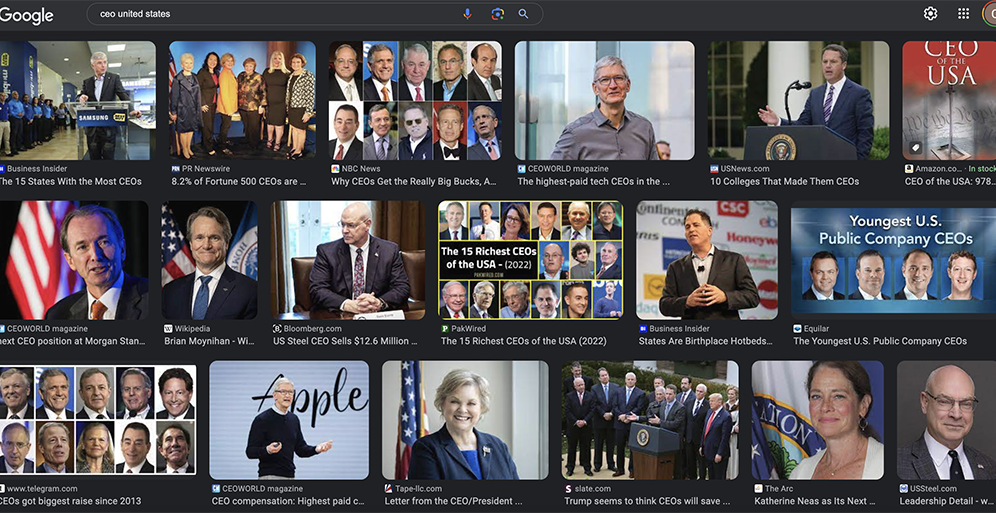

Shah said that Google’s search engine will still almost exclusively spit back images of white men, when a user tries to find an image of, for instance, “CEO United States.” The Northwest Asian Weekly’s own test of this found the same. A screenshot can be found below.

But the catch-22, Shah explained, is that Google’s search engine is returning images that a majority of users expect and won’t question. Google’s search engine is continuously trained to return such images, because of users’ interactions and expectations—driven, of course, by a trust in Google cultivated alongside Google spoon-feeding users what they should expect a certain person to look like.

But the catch-22, Shah explained, is that Google’s search engine is returning images that a majority of users expect and won’t question. Google’s search engine is continuously trained to return such images, because of users’ interactions and expectations—driven, of course, by a trust in Google cultivated alongside Google spoon-feeding users what they should expect a certain person to look like.

“People have this trust with Google. And they think that if Google is giving them this, this must be right, this must be true. And so they’re led to believe that this is what the CEOs look like,” Shah explained. “And so then they’re clicking on those things. And then Google’s algorithm learns that that’s the right thing to do, because why else would people click? … So, in other words, the bias that it had, because of its training data … gets validated. And we continue doing this.

“If Google were to then change that, and suddenly start giving people non-white and not-male results, people might think there’s something off here—you know, Google is not working right. And so we also have certain expectations. So, we are also biased,” Shah continued. “We’re just feeding off of each other’s biases.”

In other words, it’s a vicious cycle with no easy exit. In a profit-driven economy, Shah believes that the only way out is via regulation. When the Northwest Asian Weekly spoke with him in mid-January, he had just that morning given testimony in front of the Washington State Legislature regarding accountability when using AI and creating a task force to address AI.

The timeline for the task force bill stretches out years in advance, well more than three years down the road, and lacks teeth, Shah said, but the one regarding accountability may go into law if it is passed by the end of this year. Meanwhile, however, for-profit companies will continue to create problems that people like Shah and his colleagues are left to fix.

“If you were to put a toothpaste out in the market, you have to go through so many [layers of] testing and regulation, approval, and stuff like that,” Shah said. “But you can put all kinds of AI systems out without any of that. … It’s also not as simple to just point fingers at some people in some places. I think we’re all involved in that. And so my take on this is, we also all have to be part of the solution.”