By Samantha Pak

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

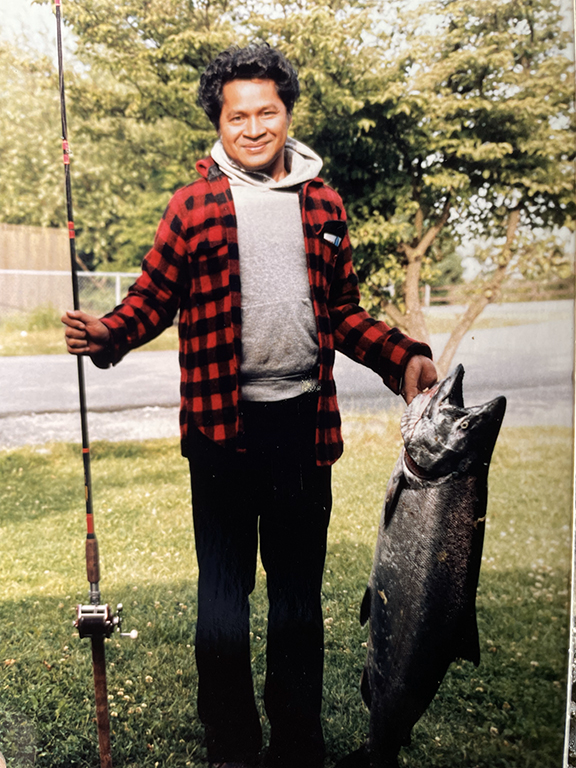

Van Sar on July 4, 2023 at Camano Island State Park, where the family has celebrated that holiday for decades. (Courtesy: Sarado Van)

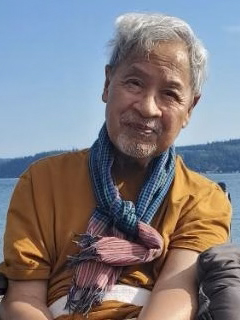

Local Cambodian elder and leader Van Sar died on Aug. 31, leaving a legacy of service for his community. Sar, who resettled in Lynnwood in 1975 after he and his family escaped the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, was 83 and died of ALS.

He dedicated his life to helping the Cambodian community—in Washington, around the country, and back in Cambodia. Sar was responsible for starting and leading many Cambodian organizations in Washington, including the Khmer Alliance Foundation, Cambodian Studies Center, and Cambodian American Friendship Foundation. His dedication to serving others also extended beyond the Cambodian community as prior to retiring in 2005, Sar worked for Washington’s Department of Social and Health Services’ Refugee Assistance Program.

“Pou (Uncle) Van Sar was involved with 90 percent of all Cambodian American organizations that were ever created in Washington, and a few other states,” said Pakun Sin, cofounder of the Cambodian American Community Council of Washington (CACCWA). “Our community lost a great leader and a ton of history about Khmer people living here in Washington.”

Helping the Cambodian community was so important to Sar that even during the advanced stages of ALS that made it difficult to speak and he was in poor condition, his son, Sarado Van, said he organized a community event to be held in his home—just a few weeks before his death. And Van said this work of helping others is something his father hoped would not die with him.

“He would like people to carry on his legacy of community work,” Van said.

Sar’s life in public service started in Cambodia, where he worked in government and served as minister of national security, prior to Pol Pot’s regime taking over the country.

Bill Oung, the other cofounder of CACCWA, had worked with Sar in the community since 1979 and said while Sar was the highest-ranking former member of Cambodia’s cabinet in Washington, he rarely spoke about it.

“He was my closest adviser in the formation of Seattle-Sihanoukville Sister City Association and Cambodian American Community Council of Washington,” Oung said. “He did so much for the Khmer community in Washington, but he was very humble and never took credit.”

When the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge in April 1975, Sar, his five children, and his sister escaped. While Sar was briefly separated from his family, they were reunited at a U-Tapao refugee camp in Thailand. They were also separated from Sar’s wife, who they later learned had died in 1978. The family first arrived at Camp Pendleton in California before permanently resettling in Washington within a few months.

As soon as he was able, Sar did what he could to help his fellow displaced Cambodians. Van recalls those early days in Lynnwood of his father working odd jobs to make money and using that money to buy a car. The vehicle was $200 and one of the doors didn’t open, but Sar got a lot of use out of it—and not just for his family. Van, who was 11 when they first arrived in the United States, said his father used the car to help the few other Cambodian families who also resettled in the area.

“Driving them places, doctors’ visits, teaching them to drive,” Van said about his father’s assistance. From that point on, Van said his father helped sponsor many Cambodian people to immigrate to Washington, “a lot of them, he didn’t even know.”

One of the strongest memories Van has of his father also involves driving. When he was 13 or 14, Van was in the car with his father; they were driving home, just the two of them. On their drive, Van spotted a city worker sweeping the sidewalk. Sar noticed Van watching the worker and told him, “There are no stupid jobs, only stupid people,” a lesson to respect people from all walks of life. This was a lesson Sar modeled as Van said his father got along with and was able to relate to all the people he met.

Sar’s outreach to the community extended beyond bringing people over from Cambodia, helping them find services and resources, and mentoring them. Van said his father also loved social gatherings. Their family was one of the first Cambodian families in the area to buy a house, so they hosted birthdays and holiday get-togethers during Thanksgiving and Christmas for their extended family and friends. Sar also organized Cambodian New Year events every April for the community so people could celebrate together.

“He enjoyed life. He laughed a lot,” Van said. “He was always carrying the sorrow of the Khmer people, while living a life full of joy.”