By Kai Curry

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

Social justice and therapy pair well together. This is true whether you are the client or the counselor. It applies especially to marginalized individuals such as people of color and LGBTQIA+s. Becca Yin, Wen Shao Lee (“Wen”), and Tiantian (Betty) Yan at Catalyst Counseling in Woodinville are part of an up-and-coming generation of therapists and counselors who draw from their own ethnic/racial identities and gender/sexual orientations to help others.

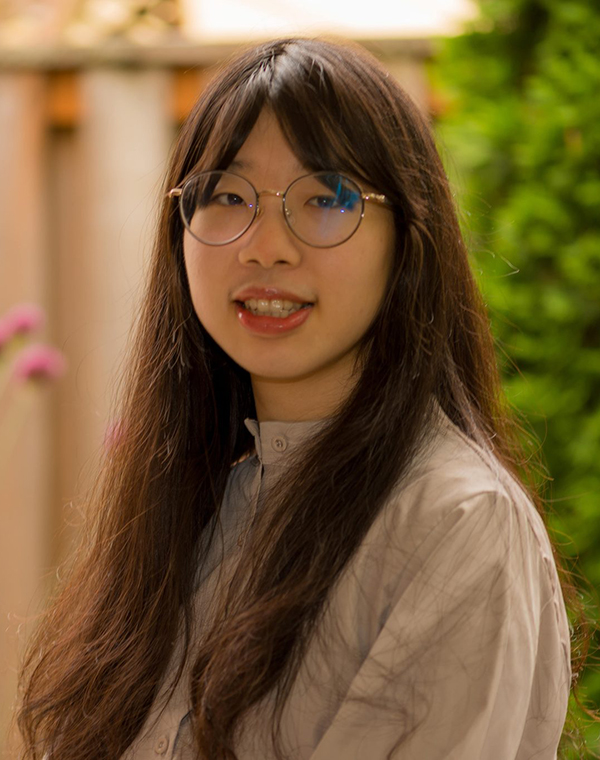

Tiantian (Betty) Yan, Licensed Mental Health Counselor Associate at Catalyst Counseling. (Courtesy of Tiantian Betty Yan and Catalyst Counseling.)

“I want to tell my clients, don’t be afraid to have multiple identities. This is a beautiful thing. You have more perspectives than other people, and you can see things from different angles,” said Yan, who was raised close to Hong Kong, then came to the United States to study. Yan noticed that, during the pandemic, when she was living in New York City (she now lives in Washington state), a lot of her clients that were people of color, and particularly Asians, were struggling “with their identities and their true feelings as a person living in the United States.”

But on the other hand, the pandemic seemed to give people the “courage to speak up for themselves,” Yan continued, such as those experiencing conflict with family members, whether it was generational or something to do with their sexual orientation. We seek therapy, in the broadest and most focused sense, on matters surrounding identity. Mixed race people want to learn about and represent both sides. Immigrants with ties to another country, same. Queer? Add that, too.

“Among Asian American clients and queer folks, these identities are necessarily going to inform each other,” Yin explained. “There’s such a diversity of experiences…What does it mean to be a person of color in America? What does it mean to be, essentially, somebody who holds multiple marginalized identities in a society that has systemic oppression working?” These are the kinds of questions that Yin, who identifies as both Asian and queer, discusses with her clients.

It makes a difference who you talk to. Yin thought hard about this when she created her bio page on Catalyst Counseling’s website.

“Something that was really important to me was self-disclosure and transparency.” She and the other therapists the Weekly interviewed know that “queer people of color are searching for a therapist who would understand. This field is far from perfect. There are a lot of barriers in terms of fit…Unfortunately, there have been too many times in which people have tried to go to therapy, only to be re-traumatized in the therapy room.”

Becca Yin, Licensed Social Worker Associate Independent Clinical at Catalyst Counseling. (Courtesy of Becca Yin)

This is something that Yin, Yan, and Lee all aim to avoid. Gone for them are the days of the therapist—usually a cis white male or female—sitting across from you, silently taking notes and telling you nothing about themselves. Therapists used to claim that “their identities would have no impact on their diagnosis or their advice, which of course it would,” said Yin. Perhaps this new approach to sharing is why an uptick is taking place in the number of people willing to seek out therapy. And, while psychology might be a Western concept, and other cultures might deal with self-help differently, there seems to be an increased importance—could be due to the pandemic—on wellness.

“One thing that I’ve noticed is people are more willing to open up…more willing to express themselves,” said Yan. And it’s not just in the U.S. “In China, I can see that the society focuses more on mental health.”

Turning to telehealth, as we did during the pandemic, has also made it more convenient for people of all ages and abilities to seek counseling.

“It’s a really important part of our lives, and I would say right now people are more proactive.” As Yan continued, since the pandemic, people are taking more time to sit with themselves and give themselves the space they need. They are also spending more quality time with relatives. “It’s a positive trend.”

Wen Shao Lee (“Wen”), Licensed Marriage and Family Therapy Associate at Catalyst Counseling. (Courtesy of Wen Shao Lee and Catalyst Counseling.)

Lee works mainly with trans teens and their parents. She noted that recently, more parents are trying to understand and respect their children’s choices and identities, and are oftentimes receptive to things like gay marriage, which is legal in Taiwan, where Lee is from. Families want to know about physical aspects, such as when kids are considering gender transitioning surgery, and how that influences their children’s mental health.

“What most concerns them is how their children will be impacted by hormones,” Wen said. They worry about their children’s depression or anxiety when they are at an age prone to both. “They’re really worried about the biological conditions—What if my child does want to change their body?”

Lee took an interest in counseling when living in Taiwan. She had a friend who was a lesbian, and who experienced conflict with her traditional parents at that time. She noticed that parents have concerns that if their children “come out” (something argued as a Western concept), maybe they will “suffer even more” as marginalized minorities or as teenagers who already go through a lot of angst during puberty. Just because we know who we are doesn’t necessarily mean we want to share that with others. Even if people are being more open now, it’s still “really hard for a lot of people,” Lee explained. “In Asian culture…in the states, it is more likely you won’t [want to] present yourself” outwardly. There is a lot of pressure to do so from both the AAPI and LGBTQIA+ communities because more exposure means more social justice.

Yin, who originally studied law, justice, and social change while at the University of Michigan, said that “there’s definitely been conversations I’ve had with people about this pressure… ‘coming out’ has the verbiage of ‘you’ve been hiding something and you’re finally being truthful’…it feels like a very intimate part” of people that maybe others are not entitled to know. Why do we necessarily need to tell others about our love lives or sex lives?

“Your identity is yours to choose how to express.” Counselors like Yin, Yan, and Lee are there to help you do that.

Yin is seeing more and more clients who say they want to “embrace all of the parts of me and make a new me, a new thing to give to the world.”

During the pandemic, “a lot of folks took time to figure out who they were or wanted to be,” Yan agreed.

Seeking out a counselor or therapist can provide a safe space to talk that maybe someone doesn’t have in their everyday lives. Even understanding parents and friends can’t meet our every need. If a counselor is like you, even better, as Lee said: “Seeing someone like yourself that you can open up to is very freeing.”

Counselors at Catalyst Counseling in Woodinville speak multiple languages including Mandarin. They strive to provide a diverse and multicultural environment. To find out more about Yan, Lee, and Yin, and their availability, check: catalystcounseling.net.

Kai can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.