By Mahlon Meyer

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

If you’ve been a longtime reader of this newspaper, you probably know that the contributions of Chinese and Chinese Americans to this country have often been neglected. Only recently, for instance, thanks to the efforts of members of our community, have the Chinese American veterans of World War II been recognized with the Congressional Gold Medal. Similarly, it was not until recently that the contributions of Chinese laborers in building the transcontinental railroad were honored.

What you may not know, however, is that the impact of Chinese culture on our society, at the deepest level, has sometimes been equally unseen.

Everyone knows about the popularity of Chinese food or Bruce Lee. And many people would recognize that other, less widespread, phenomena, such as family adoption or even western psychology, has been impacted by Chinese culture.

But the question is how.

Even in the most glaring instances of the influence of Chinese culture are hidden undertones, mechanisms that are both surprising and powerful.

Chinese food and the creation of the middle class

Take Chinese food.

Everyone knows how popular it is. But it is a secret known only to historians, it seems, as to why it is so popular.

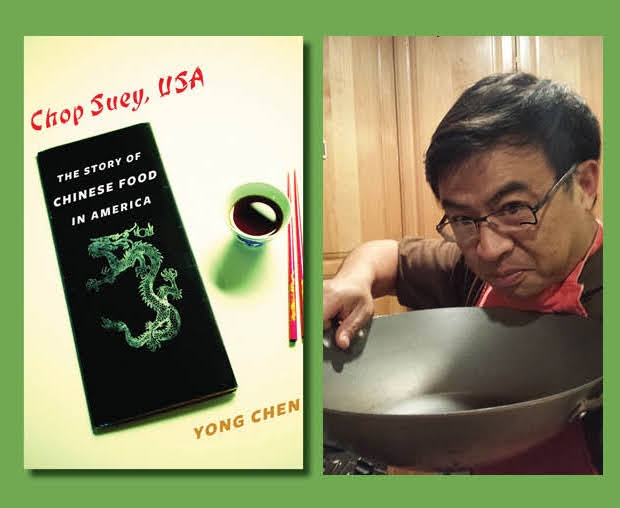

Yong Chen, a preeminent historian of Chinese food, wrote a book, “Chop Suey, USA: the Story of Chinese food in America,” that started a trend of cultural-historical analysis of the spread of Chinese food.

The reason for its spread is not what you would think.

Chen quickly dispensed with the idea that Chinese food spread simply because it was tasty.

In fact, just prior to its spread in this country, it was widely believed to be inedible by westerners. It was supposed to contain rats and other unsavory ingredients.

Rather, the spread and popularity of Chinese food came about because of the simultaneity of two things—the desire of the working classes to take part in a leisure activity of the upper classes (dining out) and the presence and cheapness of Chinese food.

That accidental convergence meant that, for the first time, working class American families could do the inconceivable: take part in what Chen calls “the American empire of consumption.”

Chen argues that the entire American empire was set up, through military conquest and intervention abroad, to create an expanding repertoire of taste and leisure at home, he elaborated in an email.

Chinese food, spreading in the 20th century, became the vehicle for what he calls “the democratization of consumption.”

In effect, it helped create the middle class as it is today, a swathe of society that defines itself in part through its ability to enjoy leisure.

Bruce Lee and Black identity

Another widespread phenomenon is likewise less well known for its deep impact on American culture.

Bruce Lee movies and their spin-offs are staples of almost every adolescent’s dreams—and in many cases encourage the study of martial arts.

“The rise of Asian martial arts in U.S. everyday cultural life through the storefront martial arts studio is an understudied phenomenon,” wrote Amy Ongiri, a professor of ethnic studies at the University of Portland, in an email.

But what is less widely known is the impact of Bruce Lee movies on Black culture. At a time when Black men and Black families were looking for alternative models of power and justice, in the 1970s, Bruce Lee movies and other similar martial arts films became the common staple for not only viewing, but for inspiration.

In her article, “‘He wanted to be just like Bruce Lee,’ African Americans, Kung Fu Theater and Cultural Exchange at the Margins,” Ongiri wrote that in many Black homes, pictures of Bruce Lee were more popular than those of Martin Luther King Jr.

While it might be easy to argue that Blacks, like other ethnic groups regularly demeaned in western culture, were simply drawn to violence and so found the movies appealing, such a depiction falls easily into the most racist stereotypes, she wrote.

Instead, Kung-fu movies regularly showed the underdog triumphing over unjust forces.

“This familiar formula helped to create the martial arts as the ultimate tool of the righteous but wronged ‘little guy’ and goes a long way towards explaining an African American interest in martial arts culture, which blossomed in this period, particularly among those African Americans who were searching for alternatives to contemporary western morals and mores,” wrote Ongiri.

Still, the movies were not overtly political—in all of Bruce Lee’s oeuvre, there is only a single scene where he overly takes on western imperialism by kicking down a sign that says, “No Chinese or dogs.”

Rather, Ongiri writes, it was that Black culture at the time lacked alternative resources for modeling the beauty and discipline of the body—African cultural motifs were not readily available.

So Bruce Lee and other Kung Fu heroes provided an alternate route to masculinity and self-realization, one that was not based in western stereotypes about demonized and violent Blacks, but rather a cunning, smart, graceful, and disciplined avatar.

Chinese babies as life givers

Just as the more popular manifestations of Chinese culture had hidden aspects, so did the more personal expressions of Chinese culture have widespread influence.

Take the adoption of Chinese babies, which peaked around 2005.

This practice coincided with and was related to the one-child policy in China, which prevented most families from having more than one child. As a result, millions of baby girls were abandoned, since in China, the girl would marry into another family.

Adopting baby Chinese girls by American families alerted American society to other aspects of Chinese culture. Parents would usually go all out to make sure their adopted daughter was exposed to her culture, in multiple ways. This often meant the entire community would learn about Chinese New Year or other holidays, or the Chinese language, or simply about China itself.

According to adoption agencies, although there were only tens of thousands of baby girls adopted, almost everyone, it seemed, knew someone who had adopted a Chinese baby.

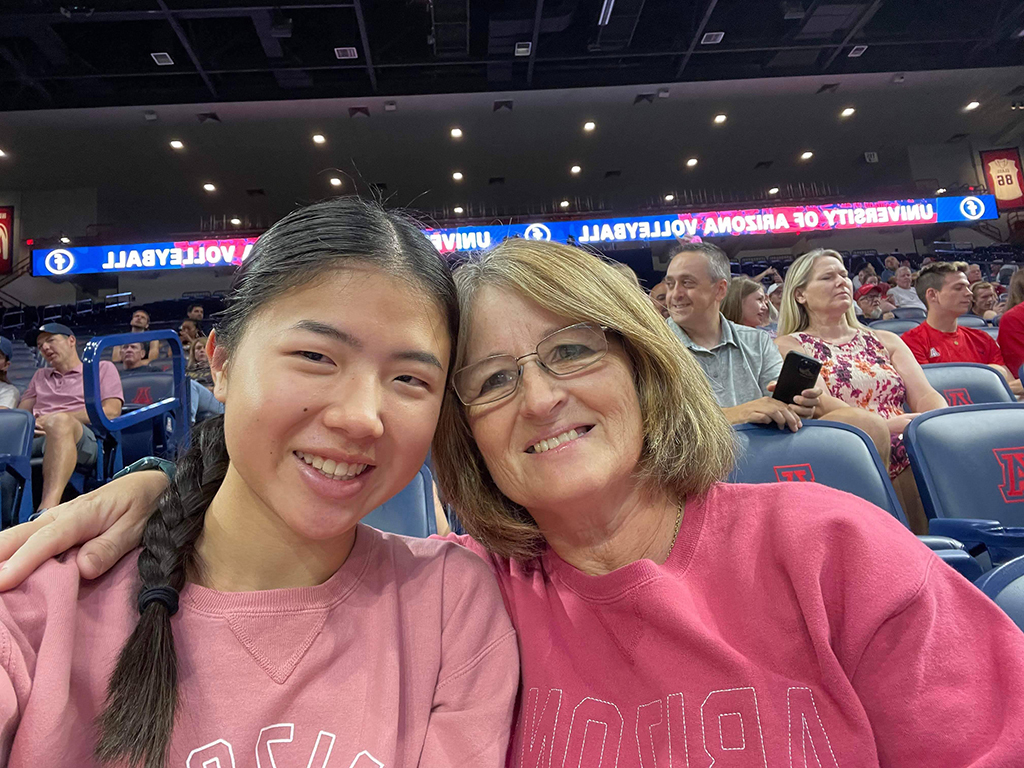

In the case of Dawn (a resident of Washington state who asked that only her and her daughter’s first name be used for safety reasons), her adoption of a Chinese baby also had a totally unintended consequence.

It brought together and empowered the Chinese community living in the greater Seattle area.

Dawn celebrated Lunar New Year every year with her daughter, Rachel, here dressed in traditional Chinese clothes (Photo courtesy of Dawn)

Dawn and her husband started out agreeing to adopt a Chinese baby girl in 2005 even though the orphanage said the infant had a tiny abnormality—her head was not perfectly formed.

But when they traveled to China, they found the orphanage had understated the case.

The baby was crying constantly and required massive surgery to correct a condition that would have killed her—her brain would continue to grow while her skull was fused flat.

When Dawn held the baby, which they named Rachel, in her arms, the baby stopped crying for the first time.

Although they had been misled, they took the baby back to Seattle where she underwent a massive, 9-hour surgery that left her head so swollen she could not open her eyes for weeks.

Again, the only thing that calmed her—and lowered her heart rate and blood pressure—was being held by her mother, Dawn.

“Although Rachel can’t see,” wrote her father in a blog later read by the Chinese community. “When she knows Dawn is nearby, she reaches out for her and is only truly comforted when in her arms.”

As Rachel grew up, the family’s efforts to involve her in Chinese cultural activities, such as Chinese dance, brought her to the attention of the Chinese community on the Eastside.

When the family ran into financial difficulties on account of bad luck, the Chinese community, knowing their story, rose up and provided financial assistance. For instance, they paid for a long vacation for the family to return to China, take Rachel to see the sights, and even visit the orphanage where she was found.

“Dear friends,” wrote a Chinese organizer on WeChat in 2010, “If you are willing to help Rachel realize her dreams, let her know that in this world, besides her father and mother, there are still many aunties and uncles who came from the same country who care about her.”

Today, Rachel is in her first year in college.

This uniting of the Chinese immigrants living on the Eastside was followed by many other major ventures, such as educational organizations and a joint effort on the part of dozens of Chinese American groups to collect masks from China at the start of the pandemic when official channels had broken down. Hundreds of thousands of masks were distributed to area hospitals and nursing homes through this organization.

Chinese spirituality and psychology

Perhaps one of the most ubiquitous but unseen impacts of Chinese culture came in the form of an area which most Americans would consider wholly western: psychology. In fact, psychology, on the whole, has made less inroads into China than might be expected.

But the influence of traditional Chinese spirituality, conversely, on western psychology has been profound.

Carl Jung, whose emphasis on dreams and symbols helped shape the course of modern psychology, was profoundly influenced by Chinese Taoism (Daoism), so much so that in his later years, he wore Taoist robes and retreated to a Taoist tower.

In his writings, Jung was influenced by the Taoist idea that reality can never fully be known, especially in language.

“Because there are innumerable things beyond the range of human understanding, we constantly use symbolic terms to represent concepts that we cannot define or fully comprehend,” wrote Jung in “Man and his Symbols.”

According to Henghao Liang, a member of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, in a paper, entitled “Jung and Chinese Religions,” Jung drew this notion from Taoist classics. The first such classic, “The Tao Te Ching,” expresses this idea as: “The Way that can be known (or spoken) is not the eternal Way.”

For Jung, dreams contained symbols that were “archetypes,” in that they expressed common symbols of the “collective unconscious” that all human beings shared.

Dreams were not to be ignored by using them to freely associate to other ideas, as Sigmund Freud (his teacher) had taught. Rather, they were to be explored as truths that led to the subconscious mind, which could never fully be known, although that might be our aim.

Jung also gave dreams the same importance, or reality, as waking life, positing them as the expression of another self we live with.

Such an idea also derived from the Taoist emphasis on dreams as a form of reality that is just as real as the waking reality we consider somehow more valid.

In the most famous passage from a later Taoist classic, “The Chuang-tzu” (Zhuangzi), the Taoist master of that name dreams he is a butterfly. But then the butterfly dreams it is Chuang-tzu, until, higgledy-piggledy, it becomes clear neither knows which is actually which. And in the end, there is no “actually.”

More recent psychology, such as that founded by University of Washington professor Marsha Linehan, known as Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) derives a core element from Buddhist practice. Here, the Chinese influence is mediated. Linehan studied “mindfulness” with Zen Buddhists, the practice of which originates in Japan. But Zen was an outgrowth of Chan Buddhism, in China, which in turn had been adopted and greatly modified from Indian Buddhism, imbuing it with distinctively Chinese elements.

DBT emphasizes finding the “wise mind,” which through a series of emotional regulation skills and analytical tools, roughly coheres to what Buddhists seek through similar practices of meditation and analysis of worldly phenomena.

Mahlon can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.