By Samantha Pak

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

Terrible things happen every day, but that doesn’t mean that everyday people can’t effect change or make a difference.

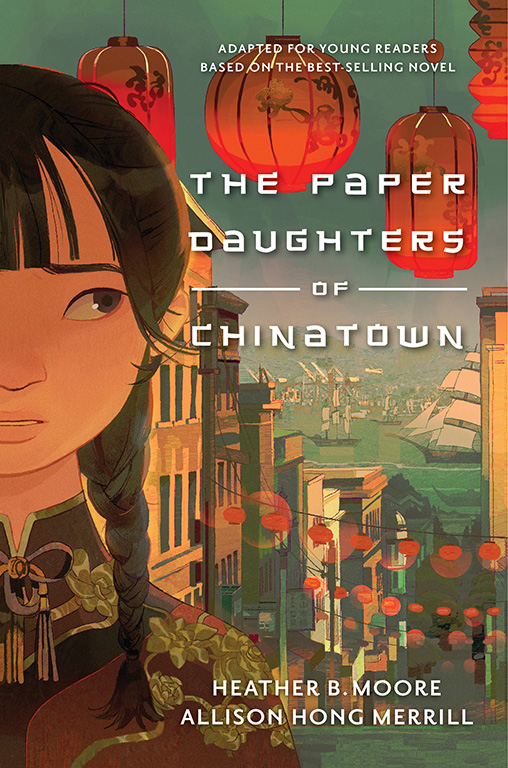

This is the message authors Allison Hong Merrill and Heather B. Moore hopes readers get in their latest book, “The Paper Daughters of Chinatown,” which hit bookshelves April 11.

The book follows Tai Choi, a young Chinese girl who has been sold to pay off her father’s gambling debt. She’s shipped off to San Francisco in the 1890s, where she’s forced to go by the name on her forged papers: Tien Fu Wu. Initially working as a house servant, Tien Fu is rescued by a local mission home, where she meets Dolly Cameron. Once the young girl—betrayed by so many adults in her life—learns to trust Dolly, the pair work together to help and free other women and girls.

The book follows Tai Choi, a young Chinese girl who has been sold to pay off her father’s gambling debt. She’s shipped off to San Francisco in the 1890s, where she’s forced to go by the name on her forged papers: Tien Fu Wu. Initially working as a house servant, Tien Fu is rescued by a local mission home, where she meets Dolly Cameron. Once the young girl—betrayed by so many adults in her life—learns to trust Dolly, the pair work together to help and free other women and girls.

Based on the true story of these two friends—whose relationship eventually becomes like a mother and daughter’s—and their work helping and rescuing immigrant women and girls in San Francisco’s Chinatown, “Paper Daughters” is a middle-grade adaptation of Moore’s book of the same name—which was released in 2020, geared toward adult readers, and focused more on Cameron and her work.

An emotional connection

The idea for an adaptation for young readers came from Moore’s publisher, who had worked with other authors who had done the same with their books. To write this book, Moore teamed up with Merrill, who she’d crossed paths with over the years as a fellow writer in Utah. Merrill was also a beta reader and editor for Moore’s original book on Cameron.

Merrill, who has mostly written historical fiction, described Moore as one of the head honchos of the Utah writing community and was flattered when the other woman asked her to work with her.

“It was unbelievable,” Merrill said about the opportunity.

Although Wu is a minor character in the original book, Merrill—a fellow immigrant (from Taiwan, in her case)—paid close attention to her and the other Chinese girls and women.

“I emotionally connected with Tien Fu,” she said, adding that the young girl’s feistiness stood out to her.

That connection continued as Merrill did her research for the book. During the process, she listened to audio tapes of interviews with Wu and Cameron during their later years in life, looking back on their work during that time.

“It was really emotional for me,” Merrill said. Wu had a hard life, but she triumphed, becoming the victor and rescuing others. Her story is one about human resilience and Merrill said it was an honor to portray it in this project.

Despite listening to Wu’s interviews, Merrill said it was still a challenge to write her story because she was starting at the beginning of Wu’s life. She had to create those moments herself to hook readers to go on this journey with Wu—taking some liberties and using her imagination about Wu’s possible feelings in those moments of betrayal. Merrill was also able to draw on some of her own experiences as an immigrant.

Reaching readers of all ages

Before writing the first book about Cameron, Moore hadn’t realized how prevalent human trafficking had been. And one of her challenges was figuring out how to write a book on that topic without being too dark or depressing. So she focused on the theme of women helping other women. This carried over when adapting the middle-grade version. Moore said they were mindful about not getting too graphic when writing for a younger audience and ensuring the story was reader friendly, despite the heavier themes of human trafficking, as well as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (which is why Wu had to change her name when she first arrived in San Francisco).

While she may have been a shoe-in to write the story since she wrote the adult version, Moore said this adaptation had to not only reach kids, but also parents and educators, adding that this pressure was the hardest part of the project.

And when asked if they were worried about “Paper Daughters” being challenged because of the subject matter, Moore said Wu’s and Cameron’s stories are easily searchable and that their book is just another way for people to learn about them outside of a textbook.

“This is our history and people can’t bury it,” Moore said.

In addition, Moore and Merrill said this story shows you don’t need to be in power to make a difference. There are other characters in the book besides Wu and Cameron—such as college students protesting and working to help the cause—who are also doing their part. They’re not waiting for policymakers or others to do something. They’re doing it themselves, a lesson for readers of all ages.

“We do what we can do,” Merrill said. “We have the power to make changes.”

Samantha can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.