By Mahlon Meyer

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

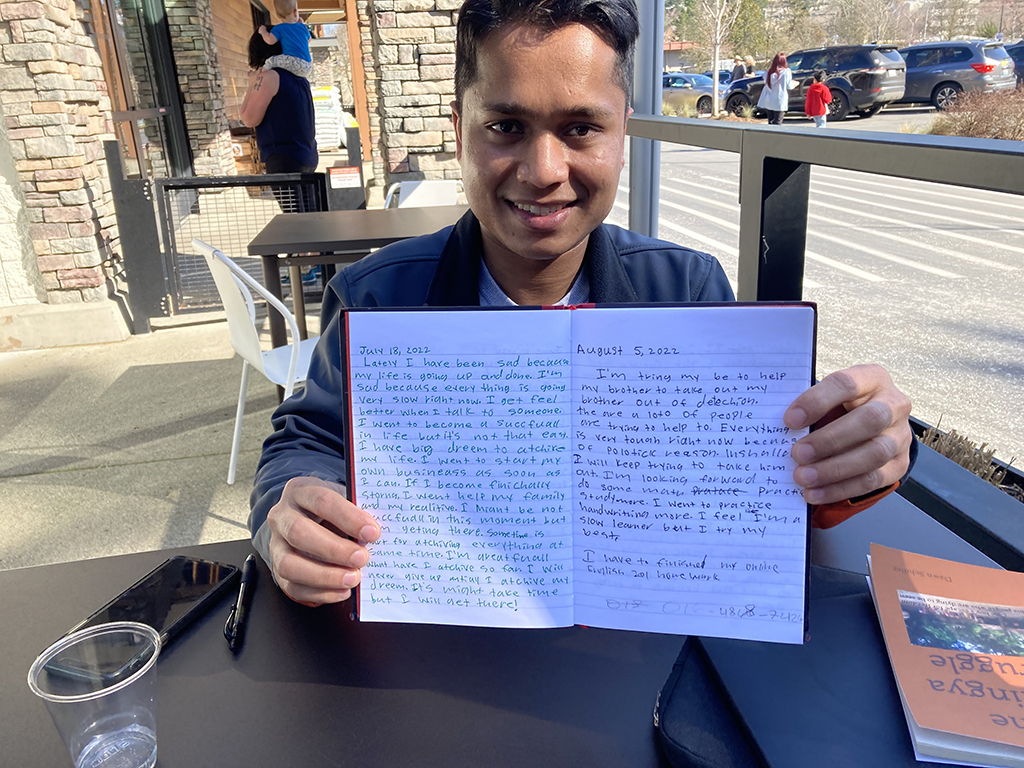

Mohamad Imran bin Zohor shows his journal where he records his feelings after talking with his family, still in a refugee camp in Bangladesh (Photo by Mahlon Meyer)

After they sent him the video, Mohamad first told his host mother on Mercer Island. She said not to contact his family in the refugee camp in Bangladesh.

The extortionist speaking on the video, which was posted on Facebook, threatened to kidnap Mohamad’s younger brothers and sisters unless he posted $5,000 to a certain account.

Fearing for their safety, the 18-year-old Rohingya refugee disobeyed his host mother, perhaps for the first time.

First, he contacted the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to see if he could speed along the countless appeals he had made to them over the years. Their answer was negative.

Then he simply told his father, in a whispered phone call, to keep track of his younger siblings.

Since there had already been kidnappings in the camp, his father was vigilant.

His ambition: to save his people

Mohamad—whose full name is Mohamad Imran bin Zohor—has been in the United States since 2016.

Standing in the tinsel sunlight of Mercer Island in an early Seattle spring, bin Zohor doesn’t look like the last survivor of a doomed people and culture. But he is one of them.

Last year, his lobbying efforts, with the help of local officials and activists, culminated in him getting his second-oldest brother out of a camp that in photos at least resembles a homeless encampment that stretches to the horizon, with periodic fires that reduce tents to ashes, ongoing violence, starvation, and sickness.

Rep. Suzan DelBene shakes hands with then-Malaysian Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob, during a visit to Malaysia last year (Photo courtesy: Rep. DelBene’s office)

Still, the lobbying he did to get his brother out could be an “ice breaker,” to use the words of a spokesperson for Rep. Suzan DelBene, who helped make the release happen.

“I just want to save my people,” said bin Zohor.

His ambition—meet with President Joe Biden, who last year proclaimed the violence unleashed by the military in Myanmar against the Rohingya people a genocide.

In 2017, at least three quarters of a million were driven from their land and thousands killed and tortured, after enduring decades of oppression.

Bin Zohor said the Rohingya had been on their land for thousands of years.

“That land used to have the Rohingya living on it,” said bin Zoho. “Now they are all gone—killed or in refugee camps.”

Family in peril

Speaking to reporters is something bin Zohor has mixed feelings about.

“Most Rohingya refugees don’t speak out,” he said.

During the term of President Donald Trump, a Rohingya activist traveled to the United States to speak with the president and others. He gave a speech at the United Nations about the plight of Rohingya refugees ignored by western countries.

His movements were tracked, his whereabouts were known by the Myanmar military, according to human rights organizations. When he returned to the refugee camp in 2021, masked men came in the middle of the night and he was brutally murdered.

But bin Zohor must speak out about his family. His mother, who he hasn’t seen since he was 12, has lung cancer. His brothers and sisters have scabies and can’t sit still for scratching.

There is no formal education except reading the Koran.

“They spend most of the day crying,” he said.

He plays a recent phone message from his father.

The tinny hurried voice drones on in a squabble about how uncomfortable his mother is. Her belly is like fire if she eats the slightest thing. The money bin Zohor sends for medicine is not enough, even though he sends half his paycheck, several thousand dollars a month, because they are afraid and unable to go out of the camp to a hospital. Most of the money is spent on food and bribes.

What really scares bin Zohor is that someone will carry through on the threat made to him on Facebook and kidnap a family member.

“They think because I’m in the United States that I’m rich,” he said.

One brother out

Getting his brother out was the beginning of renewed hope. It happened after his family fled Myanmar in 2017 as a result of the genocide and ended up in the refugee camp in Bangladesh.

“But there are the worst kind of people in those camps, who lie to families by saying they will bring children to safety,” he said. “What they do instead, is once the family has paid some money, they take the child up to their camp on a mountain.”

Then they call the family and demand more money, he added. They usually get it.

This is what happened to his younger brother, Ikram, who ended up in a Malaysian refugee camp—thousands of miles away from his family.

“The Malaysian coast guard intercepted the smugglers’ boat and took all the children to this camp,” he said.

But the conditions were so terrible, that his brother grew sick and nearly died. Bin Zohor began writing letters and contacting officials.

Travis Lumpkin, former chief of staff for Sen. Maria Cantwell, who helped bin Zohor, is half Japanese American (Photo courtesy: Travis Lumpkin)

A mutual friend on Mercer Island introduced him to Travis Lumpkin, formerly the chief of staff for Sen. Maria Cantwell. Lumpkin, as part of his earlier work, had amassed a news feed to follow the movements of important officials.

When he learned, last year, that DelBene was accompanying then Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi on a trip to Asia, that included Malaysia, he had an idea.

Working with the office of DelBene, he empowered bin Zohor to tell his story to her staff.

Bin Zohor had been making appeals to the United Nations and numerous agencies for years.

“It was serendipity,” said Nick Martin, a spokesperson for DelBene. “The stars aligned.”

During the visit, DelBene mentioned the boy’s case to the Malaysian prime minister.

The U.S. embassy, thanks to the work of other officials, including Rep. Adam Smith, was already cognizant of Ikram’s plight.

Now he was freed.

He arrived in the U.S. in December and is now living with a host family in Kent.

Bin Zohor, with the help of many, had gotten one family member out of the morass of displacement and death that has been the fate of all his people.

A solitary escape

His own story, his own escape, was more solitary. There was no one on the shores of the United States, until later, pulling for him.

Bin Zohor left his parents and younger siblings in a tiny hut with a tarp over the roof and dirt floors—in retrospect a paradise compared to where the family would later live—after the Malaysian military attacked their village. His parents made the decision to send him away.

At the age of 12, with a change of clothes in a plastic bag and his school ID (Rohingyas were not allowed passports or even to get married) and $61 from his aunt, he embarked on a journey of a matter of weeks with a human trafficker to Malaysia, where he would have the opportunity to find work or travel further.

He was on a cramped boat for almost a year as the smugglers waited for more human cargo to join. People and boys got sick and died from the fetid conditions—there was no sanitation, no way to shower, and very little food. The smugglers would simply throw bodies in the ocean.

“Day after day, we just sat in the confined quarters waiting to die,” he wrote in a book about his journey, “The Rohingya Struggle: One Boy’s Escape for Freedom All for His People.”

By the time he arrived in Thailand, where the smugglers stopped and forced him and others off, he was sick and could barely stand the smell of himself or eat with fingernails that had grown long and crusty.

In this debilitated state, he had to march through the jungle to the smugglers’ camp. Many people died and were thrown into the river.

When he got there, the smugglers called his father and demanded more money—or they would kill him. His father explained he didn’t have the money. But when they persisted, he said he would find a way.

Eventually, bin Zohor got away and walked to a Malaysian city. He sat outside a cafe, feeling more like an animal than human, hoping the owner might offer him some water.

Instead, he called the police.

The boy was taken to prison and kept there for over a year until the UNHCR secured his release. Former Washington State Governor Gary Locke, then Secretary of Commerce, also helped.

“It wasn’t about persistence,” he said, “It was about luck.”

No one goes home

“We Rohingya value family above all else,” he said.

So far, he has had no luck in getting his parents and siblings out, despite numerous appeals to the UNHCR, he showed me.

“The United Nations is not in charge of the resettlement of refugees,” came one reply.

Another reply drove home the failure of the powerful countries of the world to help all those forced to flee conflict, genocide, and disaster.

At least 89.3 million people were displaced last year around the world, according to the UNHCR.

“Many people encounter challenges in the resettlement process. To our great dismay, less than 1% of all refugees are ever resettled globally,” the UNHCR told a local official inquiring on bin Zohor’s behalf.

In the meantime, bin Zohor talks with his family several times a week.

Their home, where they live, is a rickety collection of boards and plastic tarps strung together. And yet so dense is the refugee camp, that there is barely room to turn around between their home—shack—and the wall of homes opposite.

And yet somehow, someone had gotten a picture of the dwelling. It was shown in the video demanding money.

“I’ve got to get them out of there.”

Then he added, “Along with the rest of my people.”

Bin Zohor asks community members to write to the Washington State congressional delegation and ask them to help get his family out of the refugee camp.

To reach Sen. Patty Murray, go to: murray.senate.gov/write-to-patty/

To reach Sen. Maria Cantwell, go to: cantwell.senate.gov/contact/email/form

To reach Rep. Adam Smith, go to: adamsmith.house.gov/contact

To reach Rep. Suzan DelBene, go to: delbene.house.gov/contact/

“One letter could save the lives of my family,” said bin Zohor.

To read his book, go to: a.co/d/7rLmoaA

“If people read my book, they will learn about the sufferings of the Rohingya people,” he said.

Mahlon can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.