By Andrew Hamlin

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

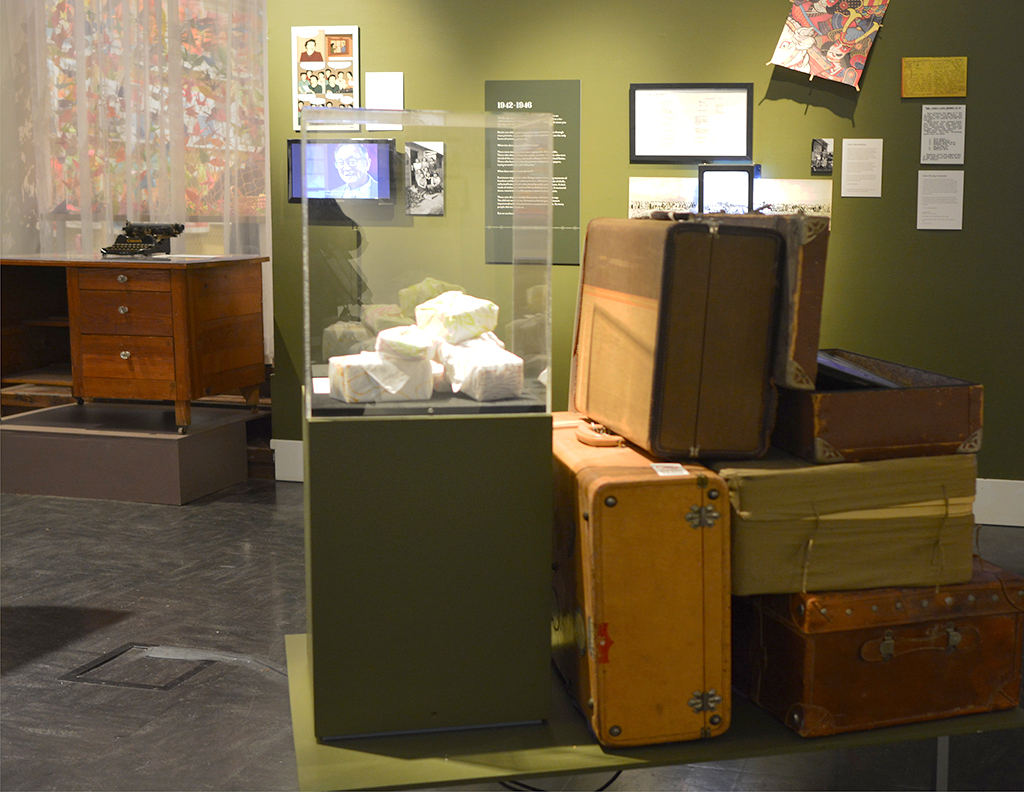

The “Resisters” exhibit, at Seattle’s Wing Luke Museum, starts out with calamity and shock. That’s deliberate. The committee designing the exhibit wants you to feel what Japanese Americans on the West Coast felt in 1942 when Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, ordered them into detainment camps. The opening section of the exhibit features government notices, personal remembrances, and a large painting, based on an actual incident, of a Japanese American Reverend taking a beating on camp soil.

President Biden acknowledged the Day of Remembrance, observed by activists for decades on or around February 19, with last year’s presidential proclamation, affirming “The Federal Government’s formal apology to Japanese Americans whose lives were irreparably harmed during this dark period of our history.”

Sadly, the systemic racism, which made Executive Order 9066 possible, hasn’t faded. Artist Erin Shigaki, who contributed original art to the exhibit and served on the committee, comes from the yonsei, or fourth generation of Japanese Americans.

“I physically grew up on Queen Anne Hill, where my parents bought a home in the late 1960s in defiance of existing redlining policies and practices,” Shigaki recalled. “The white neighbors didn’t talk to us for over a decade.

“I consider the Chinatown International and Central Districts my true neighborhoods. The places where the generations of my family before me lived and worked, and where the majority of my socialization took place when I was growing up—Japanese Language School, basketball, tennis, church, community bazaars and functions.”

One thing “Resisters” makes clear: The internees, contrary to popular thought, did not all go quietly. And they did not give up on resistance, or protest, subtle as that protest might have been.

Near the painting of the Reverend’s beating hangs a long, rectangular photo of one camp population. A magnifying lens hovers over the only man in the crowd with a beard. A heavy, thick beard. He gave up his razor when he arrived at the camp, swearing to never shave until his release.

The exhibit took inspiration from a graphic novel co-published by Wing Luke—“We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance,” written by Tamiko Nimura and Frank Abe, illustrated by Ross Ishikawa and Matt Sasaki.

Nimura, a Tacoma resident, prepared a printed copy for the exhibit. She kept in the spirit of the graphic novel, but turned her exhibit approach quite differently.

“The graphic novel was a team effort,” she elaborated. “The exhibit text is really a series of prose poems, micro-essays, all meant to encompass the ideas of different eras of Japanese American history and challenge the reader to feel and to take action.

“I wrote the text with a combination of humility and hope. Humility, because I knew that not every visitor would read the text—it is an exhibit featuring fantastic artists and artwork. Hope, because I hoped to be another artist on the wall, joining my voice in solidarity with other artists who have challenged viewers, resisted interlocking oppressions, and amplified our histories. I knew I didn’t want to be a ‘tour guide’ for the exhibit—the artists’ works speak for themselves—but I had to provide some grounding in chronology, historical context, and emotional depth.”

From the trauma of displacement, the exhibit moves through the trauma of survival, and return to society after World War II’s end. One painting shows camp buildings, anchored in one corner by a woman with a noose over her head. That’s the artist’s own mother, a detainee, who committed suicide not long after her camp release.

A teddy bear and childhood drawings sit in a case, donated by a university professor. But as a small boy in a camp, he clung to the bear for solace, and pulled crayon across paper to visualize his nightmares.

From there, “Resisters” winds its way through post-camp life: Lingering nightmares, some emotional healing, a long tough struggle to hold the U.S. government accountable. It also marks one crucial late-phase turn, as detainees and other activists turn out to march for Muslims, for Arabs, for immigrants, for Blacks, for Indigenous peoples—any American population finding itself stigmatized, scapegoated, detained without cause or justice.

“I started my [“Resisters”] piece ‘To Repair’ when I was in a residency in Oregon,” Shigaki recalled. “I was there during the Day of Remembrance season, so I was thinking deeply about my ancestors and relatives. During that time, I was also working on letters in support of Black reparations. I knew then that I wanted to create a piece that addressed the way that reparations offered a measure of healing to the Japanese American community, and could do the same for the Black community.”

Shigaki took inspiration from a close friend, Chris Rabb, a descendant of slaves who’s worked on the reparations issue as a Pennsylvania State Representative. But her piece for “Resisters” includes plenty of Japanese cultural influence.

“I was able to bring wood back from the Minidoka National Historic Site (an Idaho camp that held several thousand detainees) with which to build the altar, and I made ceramic offerings including a kitsune (fox) who is the deity of harvest.

“My mom made the bib that the kitsune is wearing. My friend Fin’es Scott helped me sow the wheat paste and painted images into tapestries, using fabric that my auntie had brought back from Japan many years ago. This artwork is very collaborative—which is the way I prefer to work. I am who I am, and I do what I do, because of those who came before me.”

Tamiko Nimura, too, continues to inspire, resist, and commemorate.

“I’m honored to be speaking at the Day of Remembrance in Puyallup on Feb. 18,” she concluded. “I’m also writing a memoir called ‘Pilgrimage,’ about Japanese American intergenerational trauma and resilience, which will incorporate and respond to excerpts from my Nisei dad’s unpublished camp memoir.”

“Resisters” shows through Sept. 18 at Seattle’s Wing Luke Museum, 719 South King Street in Seattle’s Chinatown-International District. For more information, visit wingluke.org/exhibit-resisters.