By Mahlon Meyer

Northwest Asian Weekly

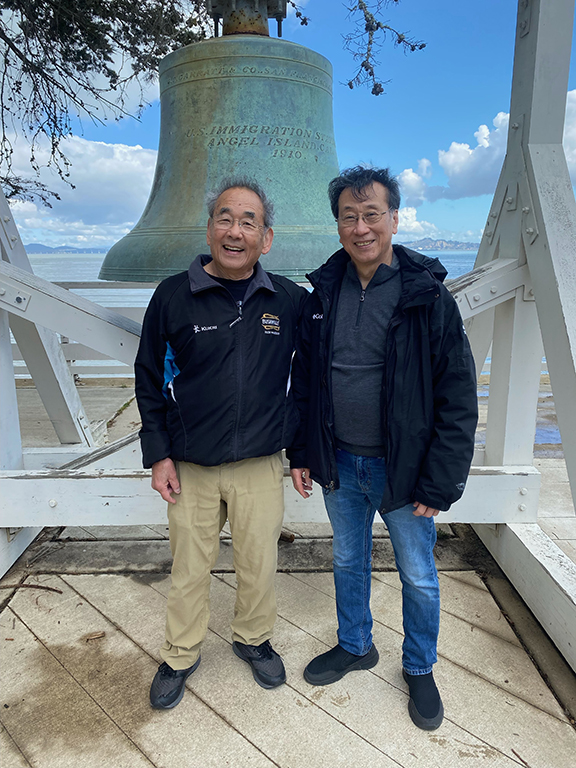

In April, Al Young took Harry Chan to visit Angel Island. The two friends were visiting San Francisco for a Bruce Lee convention. But Young, a champion race car driver who shattered racial barriers through his daredevil and consistent winning, could not shed his role as an educator. Besides being the first Asian American to win a panoply of honors on the track, he was a beloved teacher who over a span of 50 years taught a variety of subjects at various schools, including auto shop, film studies, U.S. history, American government, Chinese cooking, martial arts, and the core curriculum to students at an alternative K-12 school.

So returning to his native California, he could not resist educating his longtime friend, the owner of the iconic Tai Tung Restaurant, about something simultaneously more shameful but at the same time a source of his lifelong fight against racism and injustice.

Touring the island, Chan was at first struck by the beauty.

“You could see the ocean everywhere,” he said in an interview.

But then Young showed him the cell where his grandmother was kept for a year when she first arrived from China.

“We saw where people had written on the wall in Chinese how much they missed their homes,” said Chan.

Such a “show and tell” approach—creating a form of experiential learning for his friend—epitomized the way that Young approached life. From the race track, to the classroom, to the open streets where he still performed the lion dance or martial arts into his 70s, or even through his tenure as a member of the board of the Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI), and perhaps most of all as a father, husband, brother, and son, Young exemplified the courage to bring out the best in others by taking risks himself and by remaining fully present and supportive with those around him.

Young died on Dec. 11 surrounded by family. He was 76. The cause was complications following a heart attack.

The outpouring of grief that has filled the many communities he touched and transformed seems endless. In the few days since his death, wave after wave of former students, friends, fellow activists, and fellow race car drivers poured out their sadness and longing for him to still be present with them, as he had been for so much of his life.

“He was a true renaissance man and reached many people throughout his life, as a teacher, mentor, activist, business owner, race car driver, kung-fu Si-Hing, coach, and friend,” said Chase Young, his son. “As a son, I’m so proud of him and thankful for everything he has taught me about life, fatherhood, family, love, responsibility, loyalty, respect, hard work, and bringing positivity to the world.”

Young was born on April 28, 1946 in San Jose, California to Col. John C. and Mary Lee Young.

A documentary created by Rick Quan, “Race: The Al Young Story,” describes his early struggles with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which caused him to very nearly flunk out of school. It was not until one day, by accident, that he discovered he could read and concentrate on a book while walking, that his life transformed. Prior to that, the printed page was too demanding with the many distractions that his disorder sparked in him. But once he made this discovery, always an innovator, he began to take many-mile-long walks around a nearby lake, with a book open under his nose. He not only graduated high school, but he was accepted at the University of Washington and went on to earn a bachelor’s and a master’s in English Literature.

His boundless energy also found a channel in car racing, which began illegally on the streets in the Bay Area, but soon led him to the top of the heap and won him a sponsorship from Bardahl Manufacturing Company, formerly the largest company in Seattle.

Young described ADHD as an advantage on the track.

Waiting in his race car, watching the signal lights move from yellow to green, with his engine roaring and huge wheels spinning under him, a cloud of smoke enveloping the car, time would stand still for him, he said.

Whereas for most people, the succession of lights signaling the start of the race happened in rapid succession, for Young, he said it all occurred in slow motion, with each light filling up like a balloon being blown up—he indicated with his hands.

“One thing about having ADHD, when you concentrate, you really concentrate,” he said, in the documentary.

At times, he slipped out of the starting block one-thousandths of a second after the green light flashed.

But racing also demanded another type of concentration, one that all drivers shared, he observed, and one that united them in steering away from any kind of judgment-making based on race or anything else.

“When you’re in the car racing, if you’re thinking about your opponent—is it a man or a woman, or about what he or she looks like, or anything about him—you’ve already lost,” he said.

For years, Young was not only the first but the only Asian American race car driver, and his opponents never held it against him when he beat them.

Countless former drivers posted on his Facebook page remembering his glories and his acts of kindness and mentoring at races.

Perry Lee, a martial artist and owner of one of the largest collections of Bruce Lee memorabilia in the world, said that the study of martial arts had also contributed to Young’s concentration and confidence.

Moreover, Lee said Young was perhaps the most empathetic person he had ever known.

“You could feel it right away,” he said.

Young was also highly engaged in social activism. From the beginning, he painted his car with the symbol of a Chinese lion, to draw attention to racial stereotypes and how they needed to be broken.

“If you look at my face, you might be 80% wrong about me, based on common stereotypes, but if you look at my car, you’d probably be 80% right,” he said.

His later car, a green Dodge Challenger with the Bardahl slogan painted on, which led him to so many victories it was hard to count, he eventually donated to MOHAI, where it is on display.

In a tribute to his legend, the museum also sells miniatures of his car in the gift shop.

In working for social justice, Young was one of the most outspoken and courageous advocates for the downtrodden and his community.

Bettie Luke, who recounted that she and Young had both worked in Seattle Public Schools, said she was “pleasantly surprised” to see that Young, along with Chan, had made the long trip to take part in the 150th Golden Spike Ceremony, where his sister was giving the opening speech, to commemorate the completion of the trans-pacific railroad, built by Chinese laborers.

In articles for this newspaper, Young would not pull punches, but call out moves by authorities that he saw as racist as “bull—t” or “white supremacy.”

Vicki Young, his wife, said: “He spoke from his heart.”

Young was seemingly always available with his time and expertise and willingness to do virtually anything for anyone, as many friends and former students have shared.

“He would take care of you,” said Vicki.

Around the time he was on Angel Island, this reporter was visiting France with his wife. After getting lost and finding a small restaurant that was closed and wouldn’t serve food, I reached out to Young for help. The reason was this: the owner of the restaurant was a flamboyant French man who owned a Ford Mustang he rented out as part of his business. But he lamented that he could not find a carburetor for it in France, rendering it useless. I, in desperation, thought of Al Young (doubtless as many others had before). Because of his character and personality, I did not have the slightest hesitation about calling him up, without the slightest notice, from the middle of France, at an odd hour, and with a bizarre request. He instantly solved the problem. He told me about a special website on which foreigners could buy top-quality American-made auto parts for classic cars. I then told the French restaurant owner about this. He was thrilled.

My wife and I got our meal.

Young is survived by his wife, Vicki; son, Chase Young; daughter, Ashley Durant’ grandchildren Caden, Isa, Lilly, Peyton, Jacob, and Solomon’ daughter-in-law Kelly’ son-in-law Joel’ sister Connie Young Yu and her husband, John Yu; and many nieces, nephews, and cousins.

According to his son, he was acutely aware of funding drying up for automotive and other shop classes, where many students really gained confidence and a sense of themselves.

In his memory, and to honor his wishes, the family has started a Gofundme page for the Seattle Skills Center of the Seattle Public Schools.

“Al Young was a firm believer in public education. He felt strongly that vocational education classes needed more funding and attention,” said Chase.

Any donations to honor his legacy and continue the work he pursued for a lifetime can be made at: https://bit.ly/3uS18dS

Mahlon can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.