By Joshua Lee

Northwest Asian Weekly

Banchan (side dishes), braised short ribs, rice cake and dumpling soup, and kimchi pancake) spread out across a table on Jan. 1 2022 in Seattle, Wash. (Photo by Erin Kim)

In a packed home kitchen, the sounds of sizzling pajeon (scallion pancake) and the smell of doenjang jjigae (soybean paste stew) fill the house.

Generations of family come barrelling into the kitchen, eagerly awaiting the feast before them.

This is the reality for millions of Korean Americans, many of whom are second- or even third-generation immigrants, who come together to bond over the “foods” of their labor. Moreover, with seollal (Korean New Year) upon us, those families will undoubtedly be coming back together once more for festivities and celebratory tteokguk (rice cake soup) for the Lunar New Year.

This further begs the question: how does food, such a seemingly ordinary element of life, hold such extraordinary power?

“I definitely think there’s a strong link between food and heritage and cultural connection,” Erin Kim, a Korean American living in Seattle, said. “It’s a huge part of Korean culture that keeps me connected … I grew up eating Korean foods at home, and then being away from home, I’m starting to learn how to cook it for myself, and [I’m] realizing that it really is a big part of me.”

Kim, whose mother and father are first- and second-generation Korean Americans, respectively, uses food to deter both hunger and homesickness.

While she started out by simply pan frying pork and kimchi, Kim has moved on to larger and more ambitious culinary endeavors.

“I have a good bulgogi (seasoned grilled beef) marinade, and I make a giant pot of dakdoritang (braised spicy chicken) for my housemates,” Kim said.

“And then we reheat it throughout the week … When I went home for winter break, [my mom] made kkori gomtang (oxtail soup). I’ve always wanted to try making it, but it takes so long to make.”

Nowadays, Korean food (and Asian food in general) has gone worldwide.

What was once an almost diaspora-exclusive culinary sect in the 20th century has, with the advent of K-pop and K-dramas, exploded into the mainstream.

According to “Hallyu 2.0: The New Korean Wave in the Creative Industry,” an article by professor Dal Yong Jin at the University of Michigan’s International Institute Journal, in the late 2000s to 2010s, the second Korean Wave, called Hallyu 2.0, social media and the rise of smartphones have played a significant role in the popularization of Korean culture in the West.

Continuing into the 2020s, Hallyu is experiencing its third wave, according to Sooho Song, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. In their paper, “The Evolution of the Korean Wave: How Is the Third Generation Different from Previous Ones?” published in the Korea Observer, Song notes the immense popularity of groups like BTS, the proliferation of Korean media on Netflix and other western outlets, and the rise of mukbang, where viewers watch others eat, talk, or cook—a trend that began in South Korea.

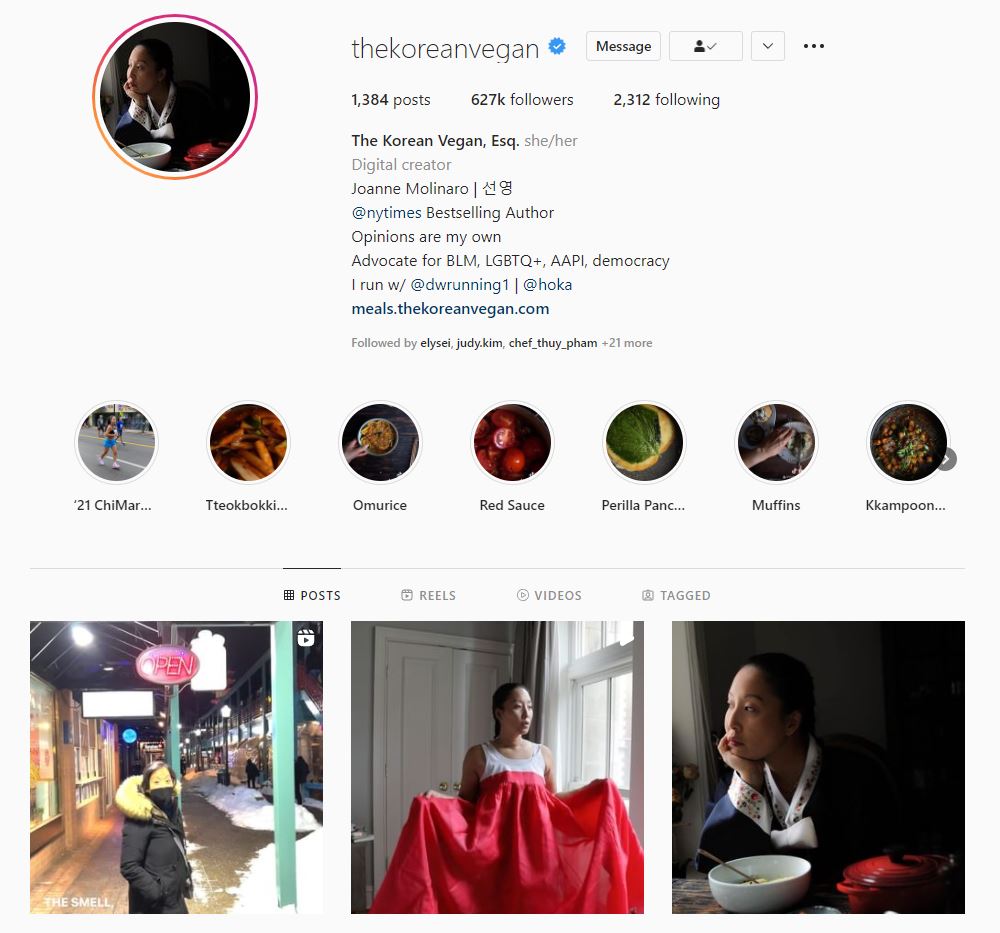

On the social media app TikTok, one of the most popular cooking accounts, with 2.9 million followers as of January 2022, is thekoreanvegan, an author and home cook who preaches the importance of good food and cultural pride.

Thekoreanvegan, whose name is Joanne Molinaro, often speaks on the cultural dissonance of growing up as an Asian American—evidently, a shared experience. The flavors of Korean food, with its distinct sour, spicy, and savory notes, can be a turn-off for unfamiliar palates.

“When I was little, I remember just thinking to myself, like, ‘Oh my god, why can’t we have spaghetti for dinner? Why do we have to have these Korean foods that are not what my friends in elementary school [are] eating at lunch or at dinner?’ … [But] as I got older, my relationship with Korean food was a way for me to connect with my mom and culture,” Breanna Humphrey, a Korean American and Ravenna resident, said.

On top of that, language, especially in such an Anglo-centric world, can serve as a barrier for second- and third-generation immigrants. When you live in a society that values English more than any other, what’s the point of learning your native language, besides novelty? Luckily, food transcends linguistic barriers.

“Whenever I go see my family, I am not fluent in Korean, so a lot of what is going on, conversation-wise, is totally flying over my head. But when we sit down to eat, it’s like we’re finally all speaking the same language,” Anna Brunner, a Ravenna resident, said.

Brunner, whose mother is Korean, travels to Korea to see her family almost every summer.

“I think one of my top favorite Korean foods would have to be (cold noodles), because it’s like a summer food in Korea … We just eat a ton of cold noodles whenever we go,” Brunner said. “It’s definitely a comfort food.”

When it comes to the fondue pot of Asian American culture, families can create their own traditions. Humphrey and her family have their own take on special occasions, taking parts from Sino-Korean tradition and combining it with American holidays.

“Starting when I was around 12, my sister and I were both like, ‘What are some things that you do in Korea for holidays?’” Humphrey said. “Now, every [New Year’s], we all make mandu (dumplings) together from scratch.

We’re all really bad at folding the dumplings and everything, so [my mom] has to do most of the work. Also, for American holidays like Thanksgiving, we don’t really cook turkey or the normal holiday spread. Most of the time, we eat Korean food.”

There are also different ways of eating that might not be familiar to an American, Brunner notes. “Knowing to eat galbi (grilled ribs) or something like that with a lettuce wrap and to add gochujang (red chili paste) or kimchi, and how to eat banchan (side dishes) before an entree, that kind of thing.”

Food is the gateway to culture, and Korean food has served as the key for these three women to connect to their families and heritage. While there will always be more foods to triumph in the future, the first steps are often the most meaningful—and delicious.

“[I’m] taking the step to learn the Korean language, and I guess that’s a part of trying to stay connected to my Korean culture,” Kim said. “But for me, cooking and food is a way that I do it, too. Because language takes so much time, and you have to study it. But I feel like cooking is an everyday thing that we can do to keep the culture alive and keep us connected to it.”

Joshua can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.