By Stacy Nguyen

Northwest Asian Weekly

When I’m not mucking about the Northwest Asian Weekly office, I work as a graphic designer. Mostly for fun, I also churn out stock clipart for pennies on the hour.

Recently, I made this Lunar New Year-theme illustration in anticipation of my favorite holiday of the year. I’m Vietnamese, so we celebrate Tết Nguyên Đán, which, similar to other countries’ lunar new year traditions, is a holiday that ushers in the arrival of spring.

I didn’t think that Lunar New Year clipart was going to be a real hot item (it isn’t), but I made it anyway, for the love of the holiday and also to rep Asian people like me/you/us in the clipart world.

When I went to tag my clipart though — in order for the clipart to be easily findable in search engines — I realized quickly that if I wanted anyone to see my clipart, I was going to have to tag the thing under “Chinese New Year.” Not only that, I would have to title it some variation of, “Chinese New Year Clipart.”

Apparently no one got the memo that we’re all supposed to call it Lunar New Year now. You know, to be more inclusive and stuff.

The beginning

When I started school at the age of 5, I couldn’t speak English, and I went to an elementary school of predominantly kids from low-income families like mine — and it was pretty ethnically and racially diverse. I didn’t really get it back then, being 5, so I wasn’t like, “Oh, diversity is so cool.” I was still only one of a handful of Asian kids and one of two Vietnamese kids in kindergarten.

I experienced my first bit of racial microaggression when a non-white Latina girl came up to me and blindsided me with, “Hey, are you Chinese?” Even though I was 5 years old, I distinctly remember being really offended by that. I was like, what the hell, no! I’m not Chinese!

Except I didn’t say it out loud because I was paralyzed by shyness.

Even at that point, I was raised by my family to have extreme pride in being Vietnamese. We are a unique, hearty stock of scrappy survivors.

And it was not really an aversion to all things Chinese that caused the offense. It was the feeling that your actual ethnic identity didn’t matter to other people — they just wanted a way to easily (and incorrectly) categorize you. In those days, Chinese was default for Asian. It flattened all of us into homogeneous sameness. That feeling carried over into adulthood for a lot of us.

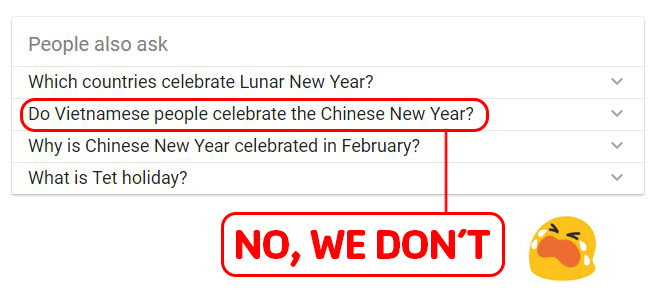

Opening a Pandora’s box via Google

When I Googled “Chinese New Year vs Lunar New Year,” you know, because it’s a fight, the first results that came up are these defensive article titles about how it’s not just new year for Chinese people. I love it. These are my people!

For Vietnamese, I can admit that a number of elements from our Tết holiday overlaps with Chinese traditions. At the same time, there are a lot of deviations, too. There are things Chinese people practice — like eating noodles — that Vietnamese do not practice. Conversely, there are a lot of things Vietnamese people do — make bánh chưng — that Chinese do not. Vietnam butts up against China and there have been centuries of cultural borrowings. But that really does not make Vietnamese people Chinese or Chinese-like.

The assumption that Lunar New Year is basically a “politically correct” term for Chinese New Year is really Sinocentric. It’s also a construct that caters to non-Asian English speakers.

While a lot of cultures with proximity and historical dealings with China have adopted elements of the Chinese version of the Lunar New Year (Japanese [pre 1873], Korean, Mongolian, Tibetan, and Vietnamese), there are also a lot of Southeast Asian and South Asian cultures (Burmese, Cambodian, Lao, Nepali, Thai, Tamil, Sinhala, Vishu, and many, many others) that have lunisolar celebrations that pull from Indic (India) traditions.

But most of us aren’t going around calling these celebrations, “Indian New Year.”

Language

I checked with my Mandarin-speaking Chinese friend from Taiwan, Tiffany Ran (also writes for Northwest Asian Weekly), about Chinese New Year as a term — because at some point, it hit me like a freight train.

Chinese people can’t possibly call this holiday Chinese New Year! That would be like an American calling Jan. 1 “American New Year”!

Tiffany told me that Chinese people call the holiday in a few different ways, with the Spring Festival translation being the most formal. In-language, Chinese tend to simply refer to the holiday as the new year.

I’m sometimes pessimistic. So I can only imagine how Chinese New Year, the term, came about.

It goes something like this:

Some years ago, a bunch of Chinese immigrants in the United States were lighting firecrackers and partying too hard like a bunch of BAMFs. Some non-Chinese Americans (probably white) ambled by and were like, “Yo, what are you guys doing?”

The Chinese immigrants were like, “Dude, we’re ushering in the new year, man!”

And the Americans were like, “No, bro. You’re like, a month too late. New year already happened.”

The Chinese immigrants then said, “Oh, no, dude. We do something different. This is the new year for us, bros.”

And the Americans were like, “Oh, so you’re saying that you’re celebrating Chinese people new year?”

The Chinese immigrants said, “Uh, sort of? I mean, it’s a little bit more complicated than that? We call it the Spring Festival.”

“Nah! Let’s call it Chinese people new year! Wait! No! Chinese New Year! It’s snappier!”

True story.

The cold, hard numbers

Credit: Stacy Nguyen/NWAW

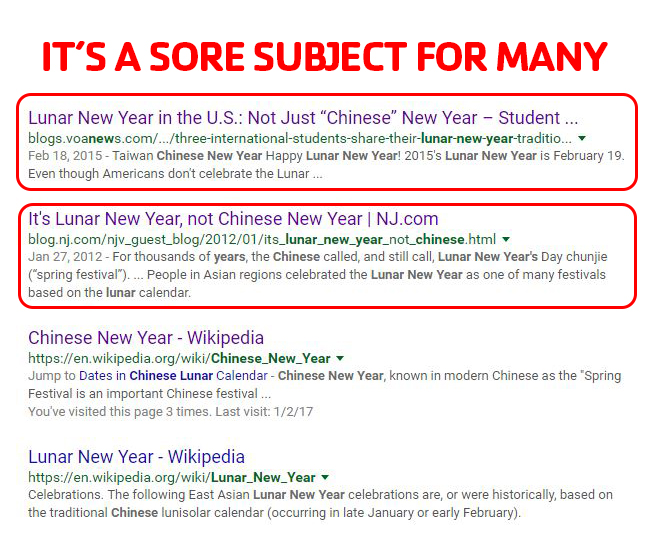

You can tell how much of a sore subject this is for me, based on how much time I spent scrolling through Shutterstock, a popular stock photo and illustration website, just counting pictures like a mad woman. On Shutterstock, there are more than 100,000 illustrations similar to mine tagged with the keywords “Chinese New Year.” In contrast, there are only about 36,000 illustrations tagged with “Lunar New Year.”

Furthermore, many of those Lunar New Year tags were basically pity tags. Of the first 100 illustrations under this tag — basically the most popular posts — 82 percent of them had “Happy Chinese New Year” or Chinese characters actually written somewhere prominently on the art. Only 18 of those 100 pictures were general enough to truly be Lunar New Year illustrations.

I used the Moz SEO (search engine optimization) tool to do a keyword search and analysis. Moz’s metrics are volume, difficulty, opportunity, and potential.

Credit: Moz

— Volume is the average number of searches performed on the keyword — basically how in demand the keyword is.

— Difficulty indicates the strength of the top 10 organic links for the keyword — the higher the number, the more difficult it is to break into the top 10.

— Opportunity is an estimate of click-through-rate for organic web results for the keyword.

— Potential is the culmination of the other metrics, basically showing return on investment on using a particular keyword.

To paint with a really broad brush, from Moz results, I learned what I already suspected — that Chinese New Year is significantly SEO-awesomer than Lunar New Year.

In conclusion

Of course I tagged and titled my clipart with “Chinese New Year.” I’m not stupid. But I felt dirty doing it. My one bit of rebellion in all of this was that I wasted a tag by writing down “Lunar New Year” anyway. It was a principled stance.

So far, one person has bought that clipart. I made about . . . $2.04 from it. And it felt good.

I mean, until we can all change the world together, we must live in it. You know?

Stacy Nguyen can be reached at stacy@nwasianweekly.com.

Tummy ulcers will limit the foodstuff you could try to eat and we have an answer to suit your needs.

You cracked me up, Stacy! I have requested my kids’ school to change from “Chinese” to Lunar New Year, was searching to see how others feel about it and found your article. I am now in the process to get the school district to be aware of how it could be offensive for some of us.

Everyone, let’s keep spreading the words. Thanks to Stacy for writing this article

I’m so glad this made you laugh! I’m also surprised that your children’s school still calls it Chinese New Year — it’s not a very inclusive term. That’s great that you are letting your school district know your viewpoint on this.

Thank you for reading and for commenting and letting me know your thoughts!

Thank you for writing this. It’s exactly what I’ve been feeling as a Korean-American for so long, but didn’t know how to voice it. Now I can just send people your article. 🙂

Thanks so much for reading this and for commenting, Jennie! I really appreciate it. And I’m glad I managed to touch on something you have been feeling!