By Stacy Nguyen

Northwest Asian Weekly

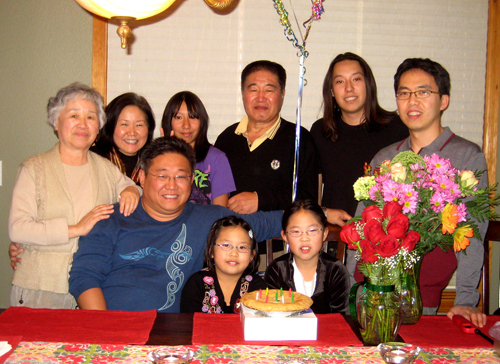

The family of Kenneth Bae saw happier times when gathered together for this 2009 Christmas photo. In the back row is his mother, Myunghee Bae, sister Terri Chung, daughter Natalie, father Sung Seo Bae, son Jonathan Bae, and brother-in-law Andrew Chung. In the front is Kenneth and his nieces Caitlin and Ella. (Photo courtesy of Terri Chung)

“It’s hard. It’s all consuming. It overshadows everything. I’m always on the phone, always on the computer <!–more–>e-mailing someone, writing letters to someone. I feel bad. I feel like I’m not entirely present. I try to be. We try to maintain as much normalcy as possible. I try to go to their games.” Terri Chung said, referring to her two daughters, ages 9 and 13.

Chung, 41, used to teach English composition at North Seattle Community College. She’s currently on leave because she found it impossible to cope with the emotional stress and struggles that came with dealing with the ebb and flow of the news cycle, which sometimes demanded all of her time and energy, on top of teaching responsibilities.

“Sometimes it’s all over the news. It’s hard to ignore it. It’s like an ever-present absence.”

Business life and imprisonment

Chung’s brother, Kenneth Bae, is an American charged and convicted by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) of planning an overthrow of its government. Arrested on Nov. 3, 2012 in the Rason Special Economic Zone, he was sentenced April 2013 to 15 years of imprisonment and hard labor. Since the end of the Korean War in 1953, no other U.S. prisoner of North Korea has been held longer.

Before his imprisonment, Bae had been living in Dalian, China, near the North Korean border. For about two years he owned a business that led foreigners on tours into North Korea. He was on one such tour when he was captured.

Established in the early 1990s, the Rason lies at the northeastern tip of North Korea, next to Tumen River, which separates a portion of North Korea from China and flows into the Sea of Japan. Relatively shallow and narrow, the Tumen has been used as a passageway to China by North Korean defectors for decades.

“He was really into business,” said Chung, explaining her brother’s motives for creating a business that led tours into North Korea. “He had a family really young and he felt very responsible because of it. He wanted to make sure he could provide for them. He had an entrepreneurial spirit.”

“He also wanted to help because he saw a need there,” she added. “He felt he was helping people contribute to the [North Korean] economy. He wanted foreign investors to contribute to the economy. He felt very compelled to do that because he had visited that area a few times before moving there. He just fell for its people, saw their hardships.”

There are state-owned and private tour bureaus and operations for travel in North Korea. Though known to be extremely controlled by the government, North Korean tourism has seen modest gains in recent years due to increase foreign investment. The idea of bicycle tours and cruise ships may seem incongruent to the typical Western image of North Korea, but they do exist. In the summer of 2011, North Korea opened its northern borders to Chinese citizens, allowing tourists to drive their own vehicles into the North Korean town of Luo. In 2012, tourists were allowed to bring their own mobile devices into North Korean, though they have to use North Korean sim cards.

Family background

Born in 1972, Terri Chung is four years younger than her brother. She describes their family as a close-knit family of four. They grew up in Seoul and were middle-class — fairly comfortable, she said. But, citing more opportunities, such as better education, their parents sought immigration to the United States.

Korean immigrants to the United States experienced a boon after 1965, with the Immigration Act of 1965, which abolished racist immigration laws that heavily favored Northwestern European immigration.

During the 1970s and 1980s, South Korea had a relatively low standard of living. According to a 2011 report by Pyong Gap Min entitled “Koreans’ Immigration to the U.S.: History and Contemporary Trends,” per capita income in South Korea was $1,355 in 1980, one-eighth that of the United States in the same year. The study also cites political “insecurity and lack of political freedom associated with military dictatorship between 1960 and 1987” as another reason South Koreans — even middle-class families like the Baes and upper-class families — to make the move.

Getting a visa was competitive. The Baes got the good news in autumn of 1984. However, their father, a notable college baseball manager and coach, got offered a job for a pro team he didn’t want to refuse. He stayed behind. His wife and two children left.

“Maybe that’s why Kenneth was so protective of me when we were growing up. He felt like —” Chung paused to find the right way to articulate her thought. “You know.”

They landed in California. Bae was a sophomore in high school and Chung just starting middle school.

“We were pretty close knit because there were only four of us. I think a brother-sister [relationship] is a little different than sister-sister. But as brother and sister, we were as close as can be. He was a protective older brother, and he felt like he had to look out for me. If we ended up at the same party, he’d be keeping a close watch on me, that kind of thing.”

“I think it was easy to adjust to American culture,” Chung added. “We had a pretty strong community where we were in California. Our church community made it easy.”

“I think it was easier for me than Kenneth because I was younger,” she added.

Chung graduated from Wellesley College with a degree in English. Bae attended the University of Oregon and studied psychology. He dropped out after two years to support his family.

Chung married and moved with her husband to Edmonds. Her mother and brother followed, settling nearby in Lynnwood. After Bae moved to China, he still visited home, coming back annually during Christmas.

Failing health

On March 17, 2009, journalists Euna Lee and Laura Ling were arrested for crossing the border into North Korea from China without a visa. They were sentenced to 12 years hard labor around June 16, 2009. They didn’t serve their sentence, as they were pardoned by Kim Jong-il a month and a half later.

In late October 2013, retired businessman and former U.S. Army officer Merrill Newman was detained in North Korea, after completing a nine-day tour. He was released 42 days later on Dec. 7, 2013.

Chung doesn’t know why her brother has been imprisoned an inordinate length of time. She is very careful and deliberate when she talks about her brother because she’s become hyper aware of how the media can positively or negatively influence her brother’s situation.

They’ve only had a handful of very short phone calls since his imprisonment. His health took a downturn — he was hospitalized from Aug. 5 to Jan. 20 — during which time their mother, Myunghee Bae, was able to visit him briefly. She reported that he had lost more than 50 pounds in three months. Since his release from the hospital, he’s presumably back to serving his hard labor sentence — eight hours a day, six days a week.

The conversations Chung has had with Bae are short, five to 10 minutes and only three have taken place in the last 16 months.

“We asked if he was okay, how he was doing, how he was holding up,” Chung said. “He just reiterated the same message, that he needed help.”

Next steps

By default, Chung is the sole contact person for all inquiries and matters involving her brother. Some of her days consist of giving interview after interview to press, managing web content about her brother, writing letters and press releases, and coordinating with the State Department, members of Congress, and media organizations. Other days consist of following up on inquiries and reaching out to experts on North Korea for advice. She’s often on back-to-back phone calls for hours at a time.

For the better part of a year, she tried to balance it all with her job of 17 years as a college instructor, with mixed success. There were days she was on national TV from 3 a.m. to 9 a.m., taught her classes from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., gave interviews well into the night, and was woken up again at 4 a.m. by reporters on the East Coast. This spring, she reluctantly stepped away from teaching, taking leave.

“It’s hard to do as a teacher,” said Chung. “You’re committed to your students. You love your job. They have to find replacement teachers. It’s very hard to walk out and have someone come in mid-quarter.”

She said she has hope that the sacrifices and the efforts are worth it.

“We want to make sure he’s not forgotten,” she said. “That’s our biggest fear. Right now, there are a lot of things happening in the world — when there are big world events, this fades from the limelight and nobody knows anything about it. We just want attention on the case. We want people to write to their representatives, write to Sen. [John] Kerry. We want to make sure there’s constant presence in the news and on social media, so that people don’t forget about this American. He’s been detained longer than any other American. It’s been 500 days.” (end)

For more information about the efforts to get Kenneth Bae pardoned and released, visit freekennow.com, The Free Kenneth Bae Facebook Page, and @FreeKennethNow. To sign a petition started by his son, Jonathan, visit change.org/freekennow. To participate in a letter writing campaign started by Euna Lee and Laura Ling, write a positive message for Bae and send to letterforkennethbae@gmail.com (letters will be screened).

*This story has been edited to correct the age of Chung’s daughter (9, not 6) and the number of years Bae operated his tour company (2, not 7).

Stacy Nguyen can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.