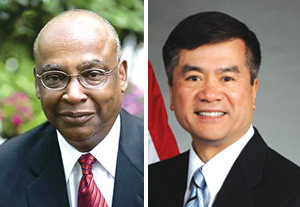

Norm Rice (left) and Gary Locke

By Assunta Ng

Being detectives and negotiators, as well as resilient and forgiving people, has allowed us to deal with many conflicts over the past 30 years.

But sometimes, even these skills are inadequate to survive the types of challenges I am going to share with you.

Locke vs. Rice

In 1995, Gary Locke, then a state legislator, announced his candidacy for governor.

My initial reaction was, “Fantastic! The first Asian American governor in the continental United States? He will be the first Chinese American governor in the United States!”

My head was dancing with possibilities for the Asian community.

But I quickly remembered that Mayor Norm Rice, a strong ally of the Asian community, was also running for governor. African American himself, he had appointed several Asian Americans to his cabinet. In fact, the Black community had criticized him for appointing more Asians than Blacks.

What was I supposed to do? I like Norm and his wife Constance. They taught me about diversity, and it changed my life.

Many of my friends were also torn between Locke and Rice. They both approached the Asian community for financial support and endorsements.

I decided that doing nothing was not the answer. Staying away from Rice’s campaign has been one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. I don’t know if the Rices have ever forgiven me.

Collecting debt

Part of the dirty work involved in publishing a newspaper is collecting bad debt. You wouldn’t imagine some of the people who pretend to be generous, but are notorious for not paying bills. If their business is having a hard time, I can understand and always do my best to help, but some simply aim to take advantage of us. I only have words for these liars and cheaters.

But, once in a blue moon, you get lucky. A 10-year-old debtor paid us a surprise visit two years ago after breaking away from his business partner and gave me a check. I was speechless.

“I owe you money,” he said. “Here is $500 first, give me time and I will pay the rest.”

The guy has heart. Now, I’ve become his client. To show my gratitude, I started using his service.

A painful chapter

There is a painful chapter within our 30 years of existence. For several months over a decade ago, one of our competitors stole issues of the Northwest Asian Weekly.

Several readers had asked what happened. “We couldn’t find your papers at Uwajimaya or any other restaurants in the I.D. Did you publish this week?”

Who did it? We hired an expensive private investigator, but the mystery wasn’t solved. Finally, we took the matter into our own hands and investigated ourselves. After much analysis, we found a pattern in the thefts. We followed the thieves, trailing the cars that transported our newspapers after they had been stolen. They brought our papers back to their office and dropped them in a dumpster behind their building. We caught them red-handed and took pictures of the evidence. Our newsroom was tense during this time because our editor went to school with my competitor’s staff. Naturally, our business was down because we focused on dealing with the problem.

We could have made them miserable.

But revenge wasn’t out goal. I was just glad we knew who did it. A group of community leaders suggested by Jane Nishita mediated the discussion between our two newspapers.

To admit their fault, we asked our competitor to donate $500 to the Kin On Nursing Home rather than give us any money. We both printed a story about the incident in our papers, and we moved on.

Protesting us

Of the thousands of controversial stories we’ve covered, none have stirred up much protest, save for an editorial we ran in 2004. In it, we echoed the appeal of General Nguyen Cao Ky, the first South Vietnamese leader to return to Vietnam, for reconciliation between communists and anti-communists.

What sparked the protest was a Vietnamese newspaper quoting our editorial. The older Vietnamese disagreed with our editorial and wanted to scare us into a retraction with hate mail and protest. We printed every single letter we received, even though they each expressed the same viewpoint, condemning the Vietnamese Communist government and us. Ironically, the writer of the editorial was our editor Carol Vu, who is of Vietnamese descent. The editor of the Vietnamese paper said that it was my fault.

He told Carol’s parents that it was the Chinese woman publisher’s fault and that it had nothing to do with Carol.

It wasn’t that I was afraid of the protest. There were only 20 or so people waving signs outside my office, demanding to meet with me and demanding an apology. I gave in to none of their demands. They attempted to shame me, but it only energized us to cover the story more.

My son said, “Mom, that’s publicity for your paper.”

What disturbed me most, however, was how deeply the ordeal hurt Carol. I’ve never seen her so sad before. Her wounds took a long time to heal.

I am happy to say that the story had a happy ending. The younger generation of Vietnamese Americans told me quietly that they agreed with the editorial. I finally invited the Vietnamese seniors to a meeting. We had a good discussion about the importance of respecting different viewpoints. Out of compassion for the older Vietnamese refugees, we gave them “face.” We printed their commentary on the importance of recognizing the old Vietnamese flag and not the new regime’s.

In 2008, that same Vietnamese paper editor who instigated the protest said to me, “You think I am against you. I am not. We support each other.”

That was the beginning of a positive relationship.

And one correction, I am not pure Chinese. My mother’s great grandmother was Vietnamese. She was born in Vietnam and she died in Vietnam.

There’s also the question of whether my grandfather was adopted or if he was the illegitimate half Vietnamese son of my great grandfather.

That secret was buried with my dead ancestors. But what I do know is that my grandfather was born in Vietnam and that his nickname in our native Chinese village was “An Nam Boy.” (end)

More conflicts to be revealed in November.