By Samantha Pak

Northwest Asian Weekly

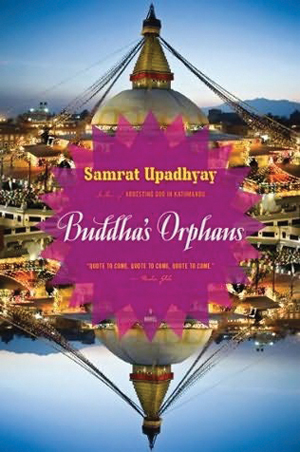

“Buddha’s Orphans”

By Samrat Upadhyay

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010

“Buddha’s Orphans” is a love story between Raja, an orphan boy whose mother drowned herself when he was a baby, and Nilu, a girl born into privilege.

Although he was deserted at a young age, Raja does not grow up neglected and unloved. In fact, the people in his life go to great lengths for him. Raja is found by a homeless man in Tundikhel, an open public space in Kathmandu, Nepal. Raja spends the first few years of his life living on the streets with Bokey Ba, the homeless man who found him.

Kaki, a woman who sells corn on the streets, helps raise the boy. She eventually adopts him as her son when her own grown son throws her out of his house.

Told from the point of view of those around him, readers watch as Raja grows from the young orphan boy, fought over by various parties who want to claim him as their son, into a young man who throws himself right into the political fray of his country.

And through it all is Nilu, whom he met while living as a servant in her family’s home. Despite her privileged life, it is clear that Nilu has struggled as much as Raja has. In some cases, Nilu has it worse. Her father died when she was young and her mother leaves her because of alcohol and drugs.

What I like about “Buddha” is that the characters are complex and they evolve as the story progresses.

My favorite character is Nilu. She’s already lost one parent and the other goes into withdrawal, barely sparing her a second thought. Nilu remains strong and independent. Nilu is also the one who seems to understand and deal with Raja the best, which is not always easy as he grows into a headstrong and stubborn young man.

What I liked most about the story is that Upadhyay portrays women in different lights, both negatively and positively. However, in the end, they are each strong in their own way.

“Paper Butterfly”

“Paper Butterfly”

By Diane Wei Liang

Simon & Schuster, 2008

Mei Wang is back in this sequel to Liang’s first mystery novel, “The Eye of Jade.”

In “Paper Butterfly,” Beijing private investigator Mei Wang has been asked by a record executive to find Kaili, a rising pop star who has been missing for four days.

As Mei begins investigating, she finds old love letters at the singer’s home. Signed “L,” Mei feels a personal connection to the letters. She learns that Kaili and her lover were part of the protests in Beijing during the late 1980s. Mei, who was working for the Ministry for Public Security, was not. She watched, torn, as her friends and college classmates were arrested, were thrown into prison for reformation, or disappeared.

The story alternates between Mei’s point of view and L’s, whose real name is Lin. Lin has just been released from prison for his involvement in the protests. As he makes his way back home, he recounts the events leading up to his arrest and how he lost Kaili. Lin unknowingly holds a key to Mei’s case.

The best thing about a mystery novel is the “whodunit” aspect. One of the ways to keep the readers guessing is to keep the characters themselves mysteries. This was my favorite feature of Liang’s characters. They are all complex and multifaceted. From Lin and his anger issues, to the record executive’s assistant’s relationship with her boss, to Mei’s relationships with her mother and sister, to how she handles the resurfacing guilt from all those past years, everyone has layers to their personalities.

It is these complexities that make a mystery interesting. Liang keeps readers wondering until the end. The way that things wrap up and Lin’s part in the mystery will surprise readers.

“A Comrade Lost and Found”

“A Comrade Lost and Found”

By Jan Wong

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007

Despite her many visits to Beijing, there is one in particular that haunts Jan Wong’s mind.

As a Chinese Canadian international student at Beijing University in the early 1970s, Wong was a devout Maoist who strongly believed in the Chinese Cultural Revolution. So when a fellow student asked for help getting to the United States, Wong did what she thought was right. She reported the other student, Yin Luoyi, to the authorities.

Wong didn’t think that she did anything wrong. Her naiveté about China and the revolution may be her excuse for not thinking twice about her actions at the time. Years later, however, the knowledge that she single-handedly ruined an individual’s life weighs on her conscience.

In 2006, four decades after the incident, Wong returns to Beijing with her husband and two sons to find out what happened to Yin. She wants to make amends. But in a city of 16 million in a country of 1.3 billion, where Yin may not even be found, Wong calls her task, “mission impossible.” This is made even more difficult as phone numbers, addresses, and even names in Beijing change on a regular basis.

“A Comrade Lost and Found” is the true story of Wong’s journey as she navigates the streets of Beijing.

Although the nature of the trip is somber, Wong injects lightheartedness into her story with amusing tidbits and comments. She often refers to her husband Norman as “fat paycheck,” which is a reference to the rough English translation of his Chinese name. In regard to her family’s safety during the car ride from the airport to their Beijing apartment, she calls her younger son “the spare.”

It is this balance of seriousness and cheerfulness that I liked about “Comrade.” The story alone is fascinating, but Wong’s musings make what could be a very serious read that much more enjoyable. ♦

Samantha Pak can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.