By Kai Curry

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

Tamiko Nimura (Photo by Josh Parmenter)

The incarceration of over 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry during World War II forever altered life for Japanese Americans and their families. For the 2026 Day of Remembrance, we spoke to Tamiko Nimura, a descendent of those who were incarcerated. Her father, Taku Frank Nimura, was incarcerated from age 10 to 14 at Tule Lake in northeastern California. Like so many others, Nimura’s father and his family were traumatically separated from their lives and livelihood, with long lasting effects.

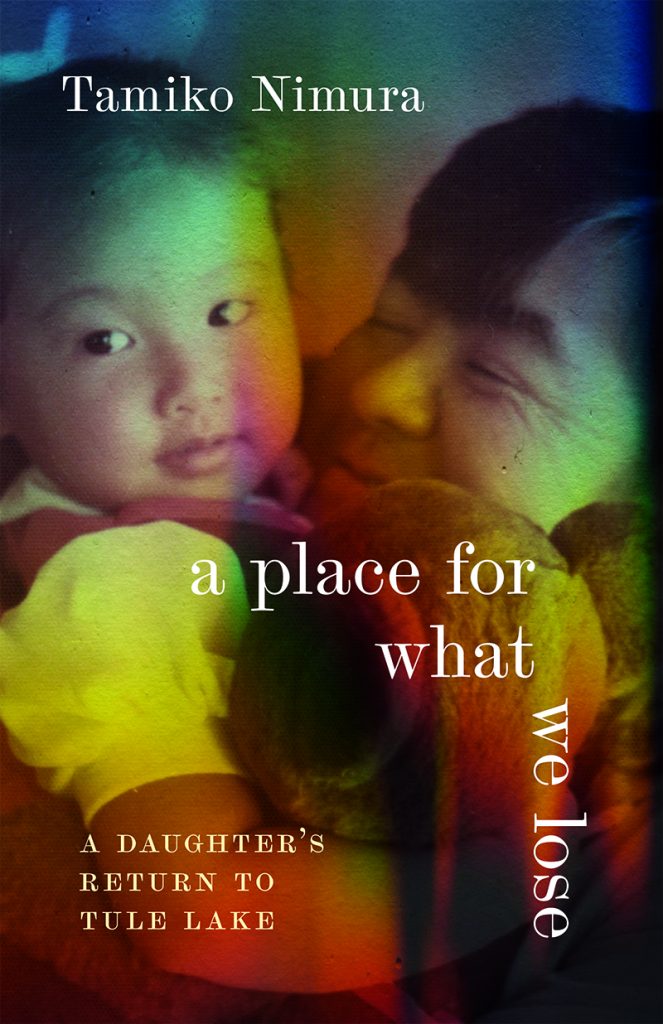

Nimura and her sister, Teruko, are third generation Japanese Americans on their father’s side, and second generation Filipino Americans on their mother’s side. Nimura’s Japanese grandparents emigrated from Hiroshima, Japan and settled in California. Her Japanese grandmother was a picture bride. They had six children and lived as sharecroppers when the attack on Pearl Harbor and subsequent U.S. response broke out. “They had very, very little,” Nimura said, yet they were a close-knit family. Nimura’s father later wrote a memoir about his experiences at Tule Lake, which Nimura has recently encapsulated in her upcoming book, A Place for What We Lose: A Daughter’s Return to Tule Lake (University of Washington Press), set to come out in April 2026.

Nimura’s father died when she was 10 years old. Although she thinks her dad probably would have been willing to talk about his incarceration—something that can be somewhat rare among those that experienced it—as a young girl, she didn’t have the same perspective towards things as she does now. So they didn’t talk about it much. After a traumatic experience of her own, related to her profession as a teacher, Nimura said that she wanted to hear what her dad had to say, and so she revisited his memoir pages. Her father had never been able to get the memoir published, possibly due to lack of opportunity in the publishing industry for writers of color at the time. We can all now read his words and experiences in his daughter’s upcoming book.

Nimura’s uncle, pioneering playwright Hiroshi Kashiwagi, was one of the first to speak about the experience at Tule Lake, Nimura told us. Her older aunts were also willing to speak to her about it. When she talks about her dad’s memoir, Nimura compares it to the famous Farewell to Manzanar, by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston from 1973. A difference that she finds is that that book was told from the perspective of adults who had the chance to go back to the scene of their incarceration, who might have been able to process the experience to some degree. “I don’t think my dad had the opportunity to do that kind of [internal] work,” Nimura reflected. She doesn’t know if he ever had any type of catharsis about his experience.

In the fifth grade, Nimura met Yoshiko Ushida, the author of Journey Home (Nimura naturally references books; her dad was a librarian). Journey Home was written for children, to help them understand the incarceration history of the Japanese in the U.S. Nimura read the book, but didn’t get to talk to her father about it before he passed. Still she remembers this as a focal point of her own education about this dark national past. Another was when she noticed that her AP U.S. History textbook only had one paragraph on this past.

“I was like, ‘Are you kidding me?’” she said. In college, Nimura picked up the trail again; her honors thesis was on Japanese American women writers. Nimura went to graduate school at the University of Washington, then found employment in Tacoma, where she and her sister still reside. She has visited Tule Lake.

“One of my aunts offered for me to go on a community pilgrimage,” Nimura said. Her aunt explained to her how important it would be for Nimura to go, too. “I thought I was going to go and observe.” Nimura was unprepared for how much the visit would impact her.

“It turned out to be emotional.” Due to her academic background, Nimura was asked to facilitate a group discussion that included her own family members. “Part of what happened for me at the pilgrimage was I really understood the power that place could have on your emotional psyche…I want to say on your body,” she explained. To walk in the same place that your relatives walked, to imagine what their lived experience was like, and to do that among community, is something that Nimura highly recommends. “Especially descendants should go on community pilgrimage because there’s a space quite deliberately created to hold you, to support you.”

In Nimura’s view, returning to Tule Lake, or to whichever of the incarceration camps, is a part of the journey of the collective grief that Japanese Americans still hold to this day. Remembering what happened, educating others about what happened, is even more important right now, Nimura continued, when this nation is witnessing a disturbingly similar political climate—and immigrants are being detained and incarcerated without any due process, just as Japanese people were in 1942. Notably, Nimura was part of the team that produced the stunning book on Japanese resistance to the incarceration, We Hereby Refuse, which she wrote along with Frank Abe. Nimura pointed out multiple similarities between then and now.

“They’re repeating it quite deliberately,” she said. She brought up the removal of mentions of the incarceration from government websites—including presidential apologies—and requests from the administration that citizens report anything disparaging someone else says about the United States.

Nimura’s own grandfather was something like Mahmoud Khalil, she said, the Algerian Palestinian who was detained by ICE in 2025 while a graduate student at Columbia University. Nimura’s grandfather was a “rabble rouser,” she described. He was arrested, in front of the family, for protesting inside of Tule Lake camp. He was eventually sent to a facility in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

“They just tried to put him as far away from anything [as they could],” Nimura said. “With no due process, no family, nothing.” Nimura’s oldest aunt wrote letters trying to find out where he was. “That very swift detention, that swift movement, the pain and the terror of such abrupt family separation, I do think really affected my dad and his siblings.”

Nimura’s grandfather, after being returned to Tule Lake, was one of the last to leave. Another punishment from the U.S. government. The family stayed at a Buddhist Temple while they figured out how to put their lives back together. “They had nothing.” Because of her own history, Nimura feels a kinship with anyone whose stories have been erased or suppressed. Since living in Tacoma, she has taken an interest in the history of the Japanese there, visible traces of which are hard to find. A lot of them were sent to Tule Lake, too. “We might have brushed elbows.”

Tamiko Nimura will be a featured speaker at the Puyallup Valley Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) Day of Remembrance event on Feb. 21 at the Expo Hall on the Washington State Fairgrounds (the fairgrounds were a holding pen for Japanese people incarcerated during WWII).

Seattle’s JACL and Tsuru for Solidarity are also part of the event.

For more information, go to puyallupvalleyjacl.org/gallery/gallery-events/day-of-remembrance-2026.

Kai can be reached at newstips@nwasianweekly.com.

Leave a Reply