By Kai Curry

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

Dr. Sally Chung

The Lunar New Year (LNY) is one of the biggest holidays of the year for Asians and Asian Americans, if not the biggest. It is much more important to many than the western New Year. A time to gather with loved ones, see out the bad, and welcome in the good. In Asia, people take multiple days off and travel great distances to celebrate. In the U.S., though, there are many who have no idea how to celebrate, if they should or want to, or what any of it means.

“Do we celebrate? How do we celebrate? How do we teach our kids? What does it mean to celebrate?” These are questions that Dr. Sally Chung believes come up for Asians in the U.S. this time of year, especially if they are second or third generation. One could also add, Chung jokingly suggested, when do we celebrate? Unlike many holidays, LNY depends on the cycles of the moon and varies yearly. Chung, a clinical psychologist with a practice in Bellevue (www.drsallychung.com), grew up with family that celebrated LNY but didn’t explain it. In their society, where they emigrated from, such as in China, her parents would have just known. It’s similar to how kids here know about Santa Claus, Chung postulated, and they would have been taught in school. For the kids of immigrants in the U.S., LNY can be very piecemeal.

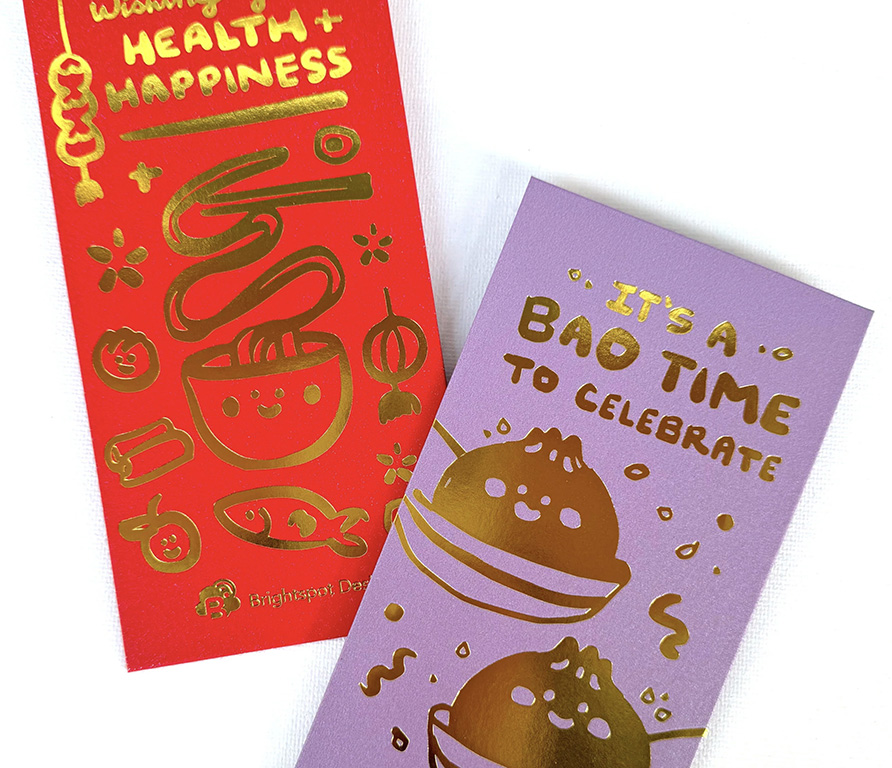

Emily Chan with Brightspot Design LNY – or all year – themed items. Image courtesy of Emily Chan and Brightspot Design

“We are Asian American,” said Emily Chan, founder and artist at Brightspot Design. Along with her husband and a small team, Chan creates Asian-themed merchandise, such as tote bags and, importantly for LNY, red envelopes. Except at Brightspot, those envelopes might be purple. They might be in English, without the Chinese characters that many younger Asian Americans cannot read. They feature elements of Asian American culture, such as the boba craze, that make them more relatable to those like Chan who are third generation. These types of items are Chan’s effort to contemporize a tradition, sometimes successful, sometimes not. She noted, for example, that in some of the stores where her envelopes can be found, people puzzle over what they are—they are larger and thicker than traditional red envelopes—which drives down sales. And red still sells the best.

“It’s the good luck red,” Chan commented. While she might think purple is cute, there are still many who believe “you’re not giving luck if you don’t give red.” Other colors are a hard sell. Like Chung, Chan wants to hearken back to tradition, while navigating the holiday in her own new way. Chan also does not know the background or meaning behind some LNY traditions. Why certain foods? Sweeping out the bad makes sense, but a lot of it was never taught. Some parents do not want to over-emphasize the traditions of home. They focus on assimilating their children into the U.S. “My dad’s side, who came from Shanghai, was like, ‘We just want you to speak English because we don’t want you to be different.’” In spite of this, one’s Asian culture remains part of one’s identity, Chan noticed. “You don’t even realize it, but it’s a part of you.”

At Chung’s house growing up, in addition to cleaning, there were always specific foods.

“There was always a noodle dish. Probably for a long life. There was usually fish. I forget why there was fish. Oranges, because oranges equate to wealth.” She remembers getting red envelopes, first with chocolate and then with money, and jokes that, since she is unmarried, shouldn’t she still be getting those? The quandary that comes up for Chung now is, how to celebrate as an adult? What if a person doesn’t have a lot of family nearby? What if only a few friends are getting together? Is it important to still have the entire traditional feast of food? Should a person be giving red envelopes to their nieces and nephews, and if so, what should they put in them? “My mom gave my dog one,” Chung laughed. “That was really cute.” The freedom to alter traditions to suit current preferences can be liberating, yet there is also a fear of losing something important.

These questions and concerns come up for Chung’s Asian American clients.

“Especially if they have kids, we have conversations about how we pass along this culture, where we were taught some of these traditions,” Chung shared. Some people have robust traditions, with extended family, and some don’t.

“What happens if your family isn’t as overt in this passing of traditions or explaining why these are the traditions, or your family isn’t in the area, or you don’t marry someone with that same background? What if you’re Asian and you marry someone white?” In many cases, the person asking the questions has become the person who is going to pass things down. Or not.

“For instance, my sister had a child. He is 2 now. He’s on his third Chinese New Year’s this year. The last couple of times, I gave him little gold coins in his red envelope. At what point am I supposed to start giving him money? Can I get away with the chocolate candies for a few more years?” Chung is joking, yet also serious about how the rules can change in a new place.

Chan doesn’t seem to stress it too much. Her LNY tradition, she told us, is more like Thanksgiving, and an informal Thanksgiving at that. They have a sit-down meal, they enjoy sharing time with the people close to them. Chan’s husband is somewhat closer to the traditions, and even shares about those traditions at their children’s school. Chan attributes at least part of this to the fact that there is a sister-in-law in their family who is first generation. Chan didn’t really grow up with an emphasis on LNY. For her family, Christmas was very important. “There is this kind of special niche, I think, that is growing and growing, especially for second, third, and fourth generation [Asian] Americans,” Chan observed.

Close up of Brightspot Design’s LNY or anytime envelopes. Courtesy of Emily Chan and Brightspot Design

Chan is featuring a special LNY gift set at Brightspot that includes a tote decorated with cute dumplings. She enjoys the juxtaposition of old and new, and will continue to see where that leads. She will continue to be flexible about how she celebrates, to create new traditions while staying curious about old ones. “We’ve had friends from China,” Chan said. “They have a whole meal and everything has meaning. That was really cool—to see the way they celebrate, with a certain fish, or the long noodle that you’re supposed to slurp up and not break, for longevity.”

For many immigrants, Chung explained, time and tradition “freeze” at the point that they leave their home countries, and unless they stay connected to that home and the people there, that will be what they pass on to their kids (provided they don’t want to suppress it, as mentioned above). The LNY, Chung said, can be a starting point for people that want to explore their cultural traditions. The way we celebrate our traditions reflects our values, Chung added. Prosperity. Longevity. Good Health. Togetherness. “It’s a way of bringing people together.”

For those that want to learn more or share LNY with children, Chung recommends https://maistorybook.substack.com/p/celebrate-lunar-new-year-2026-books?utm_campaign=post-expanded-share&utm_medium=web&triedRedirect=true.

Kai can be reached at newstips@nwasianweekly.com.