By Samantha Pak

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

Trish Hackett Nicola

Growing up in western New York state, Trish Hackett Nicola didn’t know anything about the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

It wasn’t until she started volunteering at the National Archives at Seattle in 2001 that the Magnolia resident first learned about the law that banned almost all immigration to the United States from China. She was working in the archives’ records department and met Loretta Chin, who was working in a different part of the department, organizing and indexing the roughly 50,000 personal files about people impacted by the Exclusion Act. Chin would share her findings with Hackett Nicola and answer any questions she had. It wasn’t long after that that Hackett Nicola asked to switch over to work on the Exclusion Act files with Chin.

“It was kind of shocking and so sad,” Hackett Nicola said. “I was really happy that I was working with Loretta Chin, who could help me through it. Because she could tell me stories about her life and people she knew, and just kind of explain things to me.”

“I’m a strong believer that everybody should know as much about their background, their ancestors, just to understand what made them—why they are the way they are, their strengths. They probably got [this] from these people who had to endure so much.”

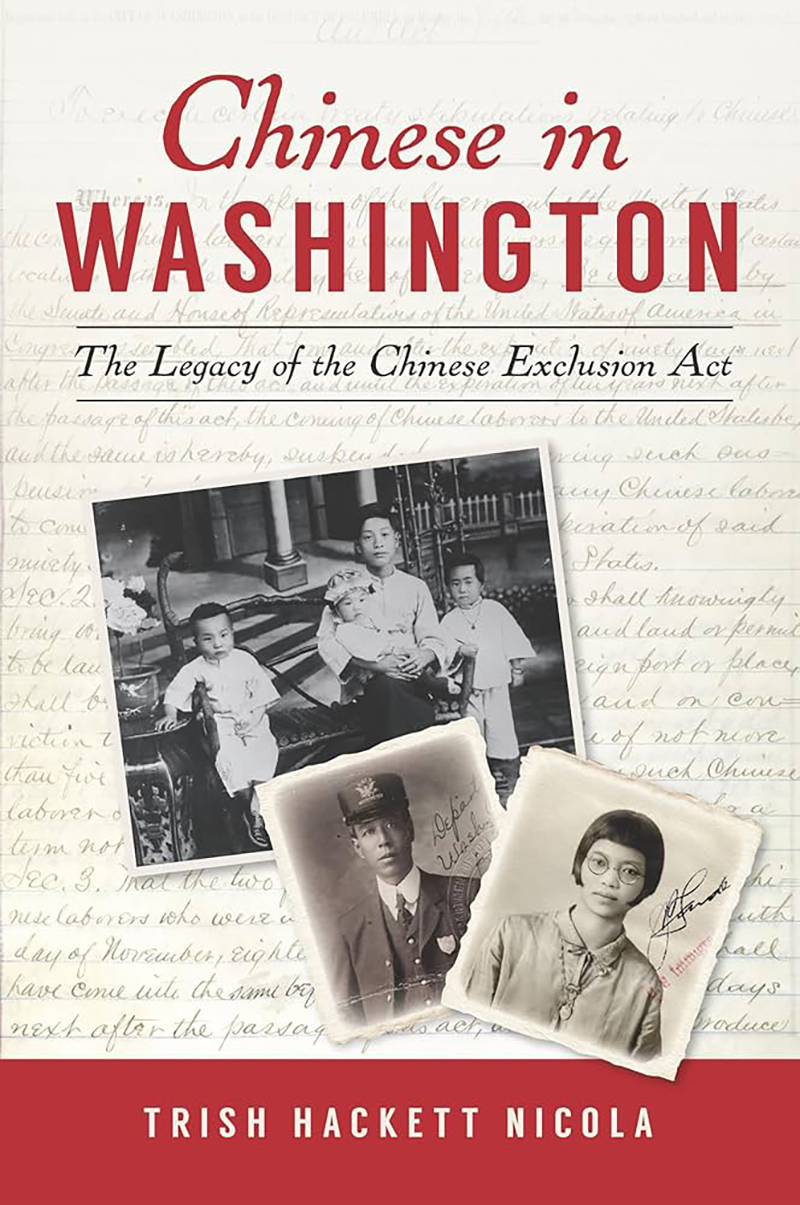

Initially, Hackett Nicola started a blog about 10 years ago chronicling the stories she discovered through her volunteer work. That blog—called Chinese Exclusion Act Case Files—currently has about 330 stories and she continues to add more to it. Her latest effort to bring these stories to light is her new book, “Chinese in Washington: The Legacy of the Chinese Exclusion Act.” The book, which was released on Jan. 6, features summaries from some of those files from the National Archives at Seattle, as well as background information about the laws and amendments surrounding the Exclusion Act.

“Chinese in Washington” has been in the works since before the COVID-19 pandemic, so Hackett Nicola said it’s fantastic for it to finally be published. She hopes this will encourage people to go to the National Archives and get a copy of their families’ files, if they’re there, or start them on their journey to find them at a different archives location if their ancestors immigrated during that time period.

“And I hope it makes more people understand what everyone went through and why we shouldn’t do it again. We’re doing it again,” she said, referring to travel bans and other laws and policies that have recently been passed.

Stories that shaped this country

The files tell the stories of people entering and leaving the country through ports in the Pacific Northwest such as Seattle, Tacoma, and Sumas in Washington, as well as Portland, Oregon, through interviews by immigration officials at the time. And everyone was interviewed—even children as young as 7.

Hackett Nicola said someone could just be going to Canada for a day, and they would be questioned when they left and when they returned to the United States if they were of Chinese descent. For example, a newspaper boy of about 14 or 15 for the Seattle Times wanted to go Vancouver, British Columbia for a newspaper convention, and she said he had to go through the entire process with immigration.

The stories from these files also serve as a record of American history and the laws and policies that have shaped this country. Through these files, Hackett Nicola learned that women who were born in the United States and had birthright citizenship could lose their U.S. citizenship if they married someone who wasn’t a citizen.

Hackett Nicola discovered this through the story of a Chinese American woman, who was born in Olympia, who married a Chinese Canadian man and subsequently lost her U.S. citizenship. This woman had about four children and had family in Seattle and Olympia, so she would travel down from Canada to visit quite frequently. And for each visit, there would be a picture of her and her family, taken by immigration officials during their interviews.

“So in her file, there are pictures of her kids over like 10 years, which is great, you know?” Hackett Nicola said. “I mean, it’s bad when it happened and everything. But for the descendants, it would be really nice to have.”

She said this is one of the reasons why she started the blog and wrote the book. People’s descendants don’t really know what’s in the files and while they may just have a short record of a person’s life, it is more information for them.

A long time coming

Hackett Nicola said her favorite thing about working on “Chinese in Washington” has been seeing it all come together, since it’s been a long time coming. She said the book is beautiful.

“I love the cover, and it has lots of pictures,” she said, before adding that is partly why it took a while for the book to be published—getting the pictures good enough to be printed.

Getting the photos print-ready was actually the most challenging part of the publishing process. While Hackett Nicola could get away with lower-resolution images online for the blog, she needed high-resolution photos for the book. There are about 80 photos in the book, and she had to relocate them in the archives and rescan them. And while it may not have been difficult work, it was tedious—from the process of finding and getting the items cleared to check out, to physically handling them without damaging the items.

“The files have a million staples in them, so just removing staples,” she said with a laugh. “So you have to be careful.”