By Carolyn Bick

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

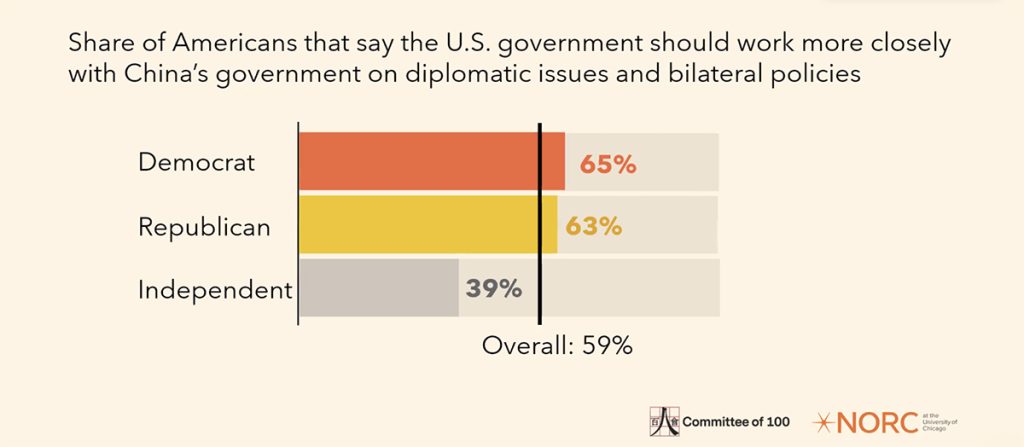

Despite the rhetoric coming from the White House, most Americans on both sides of the political aisle want the United States to find more common ground and places of cooperation with China, a new, far-ranging survey by the Committee of 100 and NORC at the University of Chicago reveals.

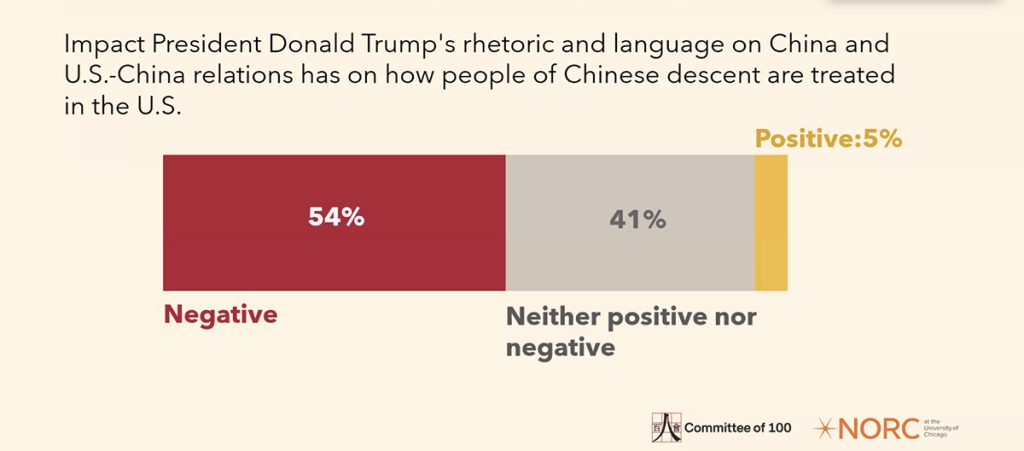

However, the survey also found—and as certain federal actors have proved—language still matters: Actions attributed to “China” instead of “the Chinese government” generated a more negative perception of Chinese and Chinese Americans. The real-world effects of these negative perceptions is particularly pronounced amongst Chinese students and researchers.

The Committee of 100 presented some of the survey’s findings on Jan. 21 in the first of a four-part series focused on American perceptions of Chinese Americans and Chinese nationals. The survey results were followed by a moderated discussion between historians Madeline Y. Hsu and Ian Shin.

Committee of 100’s Sam Collitt told audience members that though a majority of both Republicans and Democrats believe the U.S. should find common ground with China, and work with the country, the overall perception of China has swung dramatically negative since the early 2000s and 2010s. According to Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Survey, Americans’ “unfavorable” opinion of China is up from 35% in 2005 to 77% in 2025. Between 2014 and 2025, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs Survey found the idea that China is a “critical threat” to U.S. interests has also risen. These two related negative perceptions appeared to have peaked in 2023, but remain high.

Relatedly, the Committee of 100 and NORC conducted an experiment in their survey to better understand how shifts in language influence Americans’ perceptions of Chinese and Chinese Americans. Survey participants received excerpts from fictitious news articles that discussed intellectual property theft from American businesses randomly attributed in each participants’ survey to either China or the Chinese government. The survey followed these excerpts with two questions that measured respondents’ favorability towards Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans and perceptions of loyalty to the U.S. versus loyalty to China.

“Our hypothesis was that use of ‘China’ may implicate the Chinese people in the actions taken by their government, while use of ‘Chinese government’ provides a clearer delineation between the actions taken by government and its people and people with heritage from their country,” Collitt explained. “So, using Chinese government should result in relatively more favorable impressions of Chinese immigrants and perceptions that Chinese Americans are more loyal to the United States. And that’s just what we find.”

Overall, 28% of participants that read the excerpt attributing the theft to the Chinese government said they favorably viewed Chinese immigrants versus the 14% who read the excerpt attributing the theft to China.

Similarly, Collitt said, 21% of respondents in the group who read the excerpt that used “Chinese government” said that people of Chinese descent in the U.S. are more loyal to the U.S. than to China. In the group that received the excerpt with the theft attributed to “China,” that number was just 11%.

“These findings indicate that using more precise language when attributing the actions taken by a foreign government can improve the public’s perceptions of a population that is often unfairly and unjustly implicated alongside that government,” Collitt said.

Among other topics, including the history of Chinese in the U.S. and the U.S.’s historical relationship with China, Hsu and Shin discussed the China Initiative’s chilling effect on scientific advancement in the U.S.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) under President Donald Trump began the China Initiative in 2018 as a way to target and prosecute alleged Chinese spies engaging in economic espionage. But not only was the initiative ineffective—and often based on false evidence the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had cooked up—it also helped to spur a wave of anti-Asian violence between 2019 and 2020. The federal government under President Joe Biden ended the initiative in 2022, but as recently as 2024, Republican legislators in the House of Representative have introduced two different bills that would revive it.

Since the 1920s, Hsu said, the U.S. has been the primary country people travel to to conduct research and study. This has led to important global advancements—but the China Initiative, as well as current political rhetoric and action against Chinese nationals coming to the country to study and do said research has severely undermined both the U.S.’s scientific and technological potential, as well as its national security.

“As we try to make sure the United States remains the leader in terms of scientific research, we need to make sure that we are attracting just the people who are sort of the leading scientific minds in the world. And these will include Chinese,” Hsu said. “To try to label on the basis of race or national origin, who may or may not be spies, is a crude instrument. It is not going to actually improve our national security situation. … It is not an effective way, by targeting Chinese to actually address the realities of that situation. And we are also doing ourselves great harm.”

While there is some educational advocacy around the issue, Hsu said, there also needs to be advocacy from the science and technology sectors that highlights the impacts on these fields’ capacities to do business and conduct research. She also said that this hurts U.S. prospects down the line, as higher education in science and technology has been a pathway for people to enter and work in these U.S. industry sectors.

“One of the sad truths about our country is that we don’t invest sufficiently in educating our own population,” she added. “And we should, in fact, strengthen many aspects of educational access across the board, not discriminate against international students.”

Shin said that he’d witnessed firsthand the impacts of discrimination against Chinese students. Shin works at the University of Michigan. One of his roles is as the associate director of the schools’ Center for Chinese Studies, where he works with students and researchers who are here pursuing a number of fields.

“One of the things that’s very clear to me … is that they are sort of reshaping their plans as to what they want to research and also where they want to be as a result of their fear that if, for example, they were to leave this country on a summer research, that they wouldn’t be able to get back in because their visas would then be revoked at any given point,” he said. “If we’re closing doors on intellectual curiosity, this ultimately puts us in a position where we are more impoverished intellectually, culturally, spiritually, than if we were to actually let people pursue their research where they want them to go.”

Shin said that though there may be Chinese agents acting against U.S. interests, this isn’t the majority of Chinese nationals and Chinese Americans, and painting everyone with the same broad brush is harmful and inaccurate.

For instance, he said, last year, the U.S. Attorney’s office for the Eastern District of Michigan accused two Chinese students of smuggling an agricultural pathogen into the U.S. in 2024, charging them with smuggling, conspiracy, visa fraud, and false statements. The pathogen attacks wheat, rice, barley, and maize. However, not only is that pathogen common to the U.S., but in trial, even prosecutors admitted they could find no ill intent.

One of the students, Yunqing Jian, said that she didn’t follow procedure for bringing in the fungus, because she was under pressure to proceed with her research and get results. She said that she wanted to study the pathogen to figure out how to protect crops from the disease. Her boyfriend, who aided her, was sent back to China, and likely will not return.

But this didn’t stop the federal government from playing up the harm of that pathogen. In court, the prosecutor claimed it would cause “devastating harm”—a claim they did not elaborate, and that an expert factually disputed—and argued for a prison sentence for Jian four times longer than the maximum sentencing guidelines. The DOJ subsequently used certain language to twist the reality of the case.

“This is really where [the] point about precise language comes in and where the way that the case was prosecuted in the public really were based on sort of trumped up charges,” Shin said. “Plant biologists recognize, based on the specimen that was brought in, that this is actually a fungus that already exists in the United States ecological system. It’s not something that’s new. … This charge of bioterrorism was really amplifying these fears that are really unnecessary, not based on scientific fact.”

The whole situation underscores that the U.S. needs to “be able to walk and chew gum at the same time,” he continued.

“We have to be able to recognize, yes, there are certain things that we want to be able to do to keep the United States safe,” he said. “At the same time, we need to be able to do it in a way that is precise and that respects people’s civil rights and make sure that we keep Chinese and Chinese Americans safe in the United States. We really can and need to be able to do both things at the same time.”