By Samantha Pak

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

Sept. 22 marks the centennial of the birth of Seattle native John Okada, who wrote the groundbreaking Japanese American novel, “No-No Boy,” in 1957.

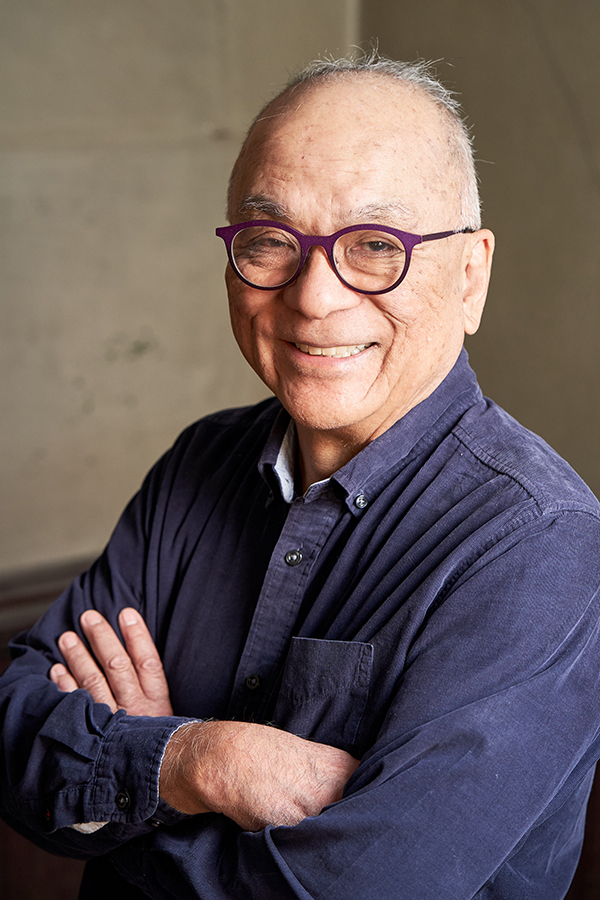

To celebrate what would be Okada’s 100th birthday, Seattle Public Library will host three programs that will explore the novelist’s life, place, and work. The programs kick off Sept. 26 and have been organized by guest curator and Okada biographer Frank Abe.

Born on Sept. 22, 1923 at the Merchants Hotel (now Merchants Cafe & Saloon) in Pioneer Square, Okada was what Abe described as a Nisei everyman. The son of Japanese immigrants, Okada was a freshman at the University of Washington when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

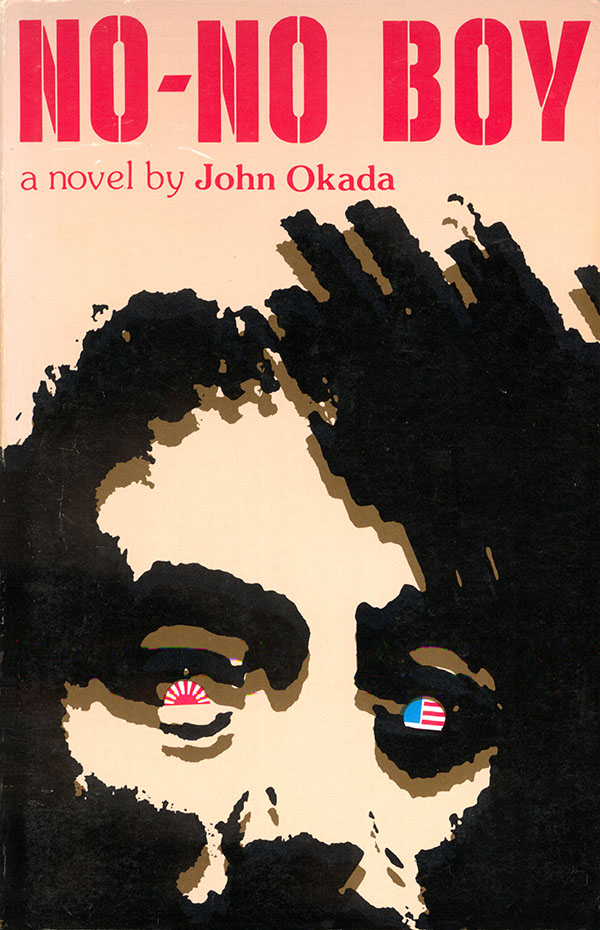

Okada’s novel, “No-No Boy,” is set in Seattle and tells the story of Ichiro Yamada, a young Japanese American man who answered “no” to two specific questions (numbers 27 and 28) on a loyalty questionnaire given to Japanese Americans who were illegally incarcerated during World War II. While many young Nisei men joined the U.S. Army at the time, Ichiro refuses and the novel follows his life post-war and the struggles he faces with his family and community as a result of his (and their) choices.

An in-depth look at the life and times of John Okada

The first library event, “The John Okada Centennial: A celebration of his life and work,” will be held on Sept. 26 at Central Library and will feature a presentation of photos from Okada’s life. In addition, novelist Shawn Wong will share how he and his friends rediscovered and republished “No-No Boy” in the 1970s, as well as the story of Okada’s unfinished second novel.

In Detroit, John Okada sat for an author’s portrait, which he sent to Charles Tuttle for distribution to the press with review copies of “No-No Boy.” (Courtesy of Roy Okada)

The series’ second event, “From Page to Stage: Adapting John Okada’s ‘No-No Boy’ for today’s theater,” will be held on Oct. 24, also at Central Library. Co-presented by the Seattle Repertory Theater, Abe will share a few scenes from the stage adaptation of “No-No Boy” that he’s currently in the process of adapting—read by local actors. There will also be a conversation with Seattle Rep literary manager and dramaturg Paul Adolphsen on the challenges of bringing a novel from six and a half decades ago to life for today’s theater audiences.

This event in particular will be a full-circle moment for Abe. He first discovered Okada—who actually was not a “no-no boy” and did serve in the military during the war—as a young man. With a degree in theater and training as an actor and director from the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco, Abe has always wanted to see the Japanese American experience on stage. He even used monologues from “No-No Boy” as audition pieces.

“As an actor, I was fascinated by his novel,” Abe said about Okada, adding that the novelist also used to work at the Central Library following the war.

The Okada series will culminate with “The Postwar Seattle Chinatown of John Okada” on Nov. 19 (location to be determined). Seattle’s Chinatown is its own character in “No-No Boy,” and this event will examine the legacy of Chinatown hotels and other businesses owned by local Asian American families that have existed for decades—even harkening back to Okada’s time. The panel will feature family historian Shox Tokita, former Seattle City Councilmember Delores Sibonga, and author Dr. Marie Rose Wong.

While all library events are free and open to the public, registration is required for these programs. For more information and to register, visit spl.org/calendar.

Lessons and legacy

Abe described “No-No Boy” as the “great Japanese American novel.” However, he noted, when the book was first released, it was not well received by the Japanese American community. At the time—the 1950s—he said they focused on celebrating the valor and sacrifices made by the Nisei generation that led to the community’s acceptance in postwar society. But now, “No-No Boy” is often taught in the classroom, a legacy Abe wants to see live on.

John Okada flew dangerous missions in 1945 over the Japanese coastline intercepting and translating ground-to-air radio transmissions as part of “The Flying Nisei,” as he fictionalized at the end of the preface to “No-No Boy.” He wrote a message to his brother Roy on the back of this photo with his B-24. (Courtesy of Roy Okada)

“I really want to see [‘No-No Boy’] continue to be used in high schools and colleges as it has been in the last 30 years,” Abe said.

In addition, Okada’s book is another opportunity to convey the ongoing legacy of incarceration and injustice that still echoes today, Abe said. Despite the Japanese Americans’ illegal incarceration during World War II being a cautionary tale, history has repeated itself, he said, pointing to some of the actions of the previous administration.

“‘Never again’ is now,” Abe said.

Stesha Brandon, literary and humanities program manager for the library, added that Okada’s contributions to literature cannot be overstated.

“It’s cool to be able to have that conversation now, before we forget, hopefully,” she said.

Creating a welcoming library for everyone

Abe’s partnership with the library and the Okada series is part of the library’s guest curator program.

“Frank is the best, so it’s great to work with him on this project,” Brandon said.

Brandon started the program in 2021 and said it’s part of the library’s efforts to develop community-responsive and community-led programming. Since its inception, there have been two guest curators per year, typically in the fall and spring. Brandon said guest curators like Abe have full creative control over the programming, receive a stipend for their work, as well as a budget for marketing and to pay participants (panelists, speakers, etc.).

Past guest curators include D.A. Navoti, Olaiya Land, Shin Yu Pai, and Claudia Castro Luna. Their themes and topics have ranged from the idea of growing up, to radical self-care, to keeping creativity alive.

“Every year is a little different,” Brandon said, adding that they have received a really strong response from the community for the programs.

She said the guest curator programs are focused on highlighting underrepresented communities, sharing power with community, and bringing in folks whose perspectives are different from hers.

“I’m a white woman,” Brandon said. “We’re covered on that.”

The library is for everyone, she said, and one hope she has for the guest curator program is to help people feel more welcome—especially those who may not think the library is for them.