By Mahlon Meyer

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

The talk flowed easily. Then it turned to travel, and I said, “You know, for many Americans, spending a month driving back and forth across the country with a parent would be a rare opportunity, but by the end of the time, some might find it hard not to feel a little annoyed if the parent reverted to old habits of nagging and even criticizing.”

The talk flowed easily. Then it turned to travel, and I said, “You know, for many Americans, spending a month driving back and forth across the country with a parent would be a rare opportunity, but by the end of the time, some might find it hard not to feel a little annoyed if the parent reverted to old habits of nagging and even criticizing.”

Lily Yin, who is in her 50s, was silent for a moment. Then she burst out crying. And I realized just how different many Americans are from many Chinese—including the Chinese immigrants living here.

“To still have someone who is willing to nag you or criticize you,” she said, now openly weeping for the first time in the 10 years I have known her. “This is a blessing. I have had so many friends whose parents died in China, and they couldn’t even go back to attend the funeral.”

After not seeing her 83-year-old father, Fushan Yin, for three years, due to the lockdowns in China, where he lived, and other travel restrictions during the pandemic, Lily is embarking this month on a cross-country road trip with him and her son, to the East Coast of the United States.

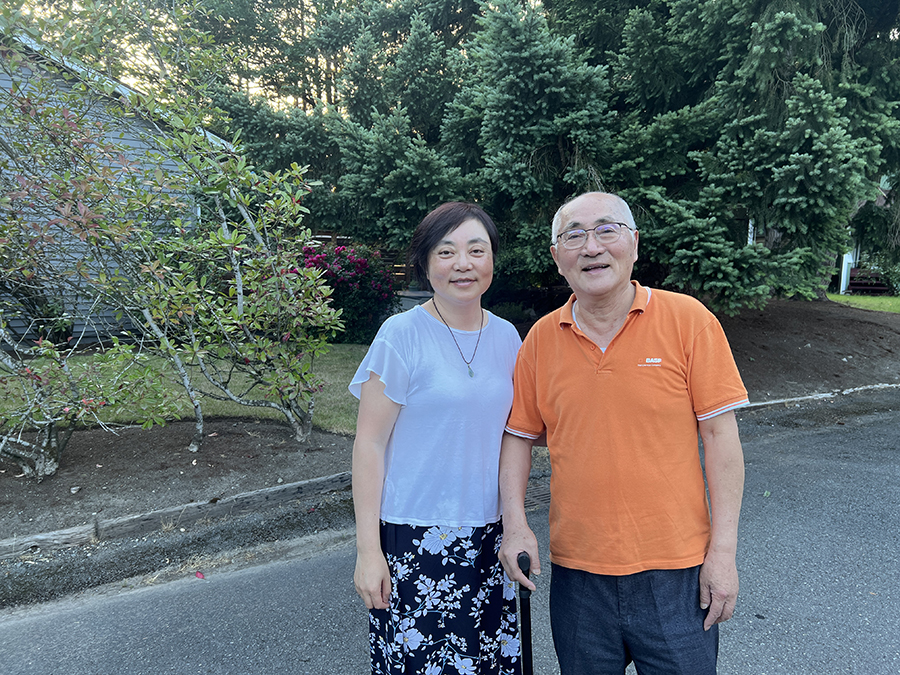

Lily Yin and her father, Fushan Yin, as they prepare to embark on their cross-country odyssey. (Photo courtesy of Lily Yin)

Travel for a new life

Psychologists who study trauma say that travel can be a way to heal. But they caution it must be simple. Some simply like to go to the beach and sit. Others encourage solo travel.

But in the wake of the pandemic, others see travel as an opportunity to create a new narrative about one’s life.

“Given its severity, the COVID-19 pandemic could be considered as existential hapax [once-in-a-lifetime event], a crucial moment of life and an intense experience that led to significant physical, emotional, and spiritual transformation,” wrote Li Miao, a tourism researcher, and his co-authors, in “Post-pandemic and post-traumatic tourism behavior,” in Annals of Tourism Research, July 2022. “In the post-pandemic era, travel for purpose and morality may become more prevalent as people engage in a deeper introspective reflection in searching for purpose and constructing a revised life narrative.”

A cross-country road trip

In Lily’s case, the trip was never planned as a way to heal anyone—much less rewrite her or her father’s life.

But when she was finally able to visit her father in November of 2022, precisely three years after she had last seen him, in Hangzhou, she was shocked at how much he had changed.

The sprightly, energetic 80-year-old she remembered had transformed into a decrepit, discouraged wreck.

Some of it was psychological.

Upon her father’s finally retiring after his 80th birthday—he had been a professor, a government worker, and finally a consultant in chemical engineering to companies doing business in China—he had wanted only to enjoy his newfound freedom through travel, his great love, which he had deferred for so many years that had crept into decades then his entire life.

Now he was free.

But immediately the pandemic hit.

“The Chinese people were nervous,” said Lily, who remained in contact with her father frequently through conversations over the social messaging platform WeChat. “But they wanted to work with the government.”

She heard how her father, every three days, would descend the stairs of his apartment building to get a Covid-19 test.

The isolation preyed on him.

“People were also scared, because the government at that time was talking about how many people were dying in the US,” she said.

By the time she returned and saw her father, he had been transformed into someone she barely recognized. The overconfident, jovial adventurer had become overly timid about his health.

“He was walking with a cane, and when he took one step forward, he would have to wait for his foot to be entirely stable and firm on the ground before even starting to raise his other foot to take another step,” she said.

Over the two weeks of her visit, she supported him multiple times a day on walks, helping him to regain his confidence.

By the end, he could walk much faster.

Lily thought back to a trip she had taken with her father and aunt in 2016 from Seattle to Yellowstone, when they had rented an RV, and her aunt had regaled them with stories about how the family survived during the Cultural Revolution in China—her grandfather was a small business owner and was therefore looked down upon, considered not belonging to a revolutionary class.

During her most recent visit, in November, Lily proposed to her father another driving trip—this time across the entire length of the country, to help her son settle into a new job in Virginia.

At first, he was hesitant. But as his physical strength returned, he quickly warmed to the idea.

Soon, his ardor for the trip outweighed her own.

The trip was planned for the summer of 2023 so he could escape the hot and humid summers of Hangzhou—but more importantly be part of the exodus of his grandson.

“We will have three generations riding in one van,” said Lily, excitedly.

Restructuring the brain

Priscilla Lui, assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Washington. (Photo courtesy of Priscilla Lui)

According to Priscilla Lui, an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Washington, travel can indeed help people gain a new perspective on negative experiences in the past—no matter how big or small.

“From my personal experience, traveling solo or with close ones can be beneficial in terms of relaxation, mindfulness and immersion in nature, cultural learning and exchanges, and relationship building (when traveling with others). These can vary in terms of the goals and types of traveling and destinations, and planning,” said Lui in response to emailed questions from the Northwest Asian Weekly.

While some stress from travel can arise, the overall gains often make up for them.

“As with most things, I believe there may be hassles that bring up stress and negative emotions as part of the travel, such as sticking to an itinerary, not adjusting to a new environment, not seeing eye to eye on activities during the trip when traveling with others. Even then, depending on the degree of these hassles and the nature of the relationships, the benefit can outweigh the cost. Psychological research has shown the benefits of cognitive restructuring for example, that even in times of stress and adversity, people can reframe negative experiences,” she said.

Taking precautions

When asked about precautions, Lily said they would be masking up—but not due to COVID-19.

“We have been hearing so much about the toxicity of wildfire smoke, and since we’re traveling as a single unit in a van, it’s the smoke we’re most worried about,” she said.

Her father always masked up when he went out in public in China. And on his plane flights over to the U.S., he continued to wear a mask.

“But when he arrived, he saw that no one was wearing a mask,” said Lily. “So he feels much safer over here.”

Still, health officials caution that COVID-19 is still in transmission here, although rates are falling. A host of other viruses that can cause serious complications, such as R.S.V., are also prevalent.

According to Marion Pepper, professor and chair of the Department of Immunology at the University of Washington, individuals who are 65 and older or are immune compromised should get a booster if it is more than six months after their last booster or infection and they are going to be “significantly exposed” during travel.

“Additionally, masking in enclosed spaces like an airport or airplane is still a really good idea, especially for at-risk individuals. Together, these protective measures will help to prevent infection,” she said.

(Both Lily and her father are boosted.)

“Obviously, COVID isn’t completely ‘over,’ said Pepper. “Everybody knows someone who’s been infected with Covid-19 over the last few months. However, we are in a very different phase of this pandemic than we were even a year ago. In addition to vaccines that largely prevent severe illness and death, we also have effective antivirals like Paxlovid. So I think it is important to highlight that while the COVID health emergency is over, it is still OK to take precautions to keep yourself healthy.”

Building well-being together

But Lily is not letting the fears of contagion and wildfire dampen her enthusiasm for the trip.

In fact, the presence of three generations, particularly in an Asian family, can provide positive reinforcement for all. For Lily’s father, spending time with his grandson, who is starting a job at a high-tech company on the East Coast—and delayed his start so he could take the trip to be with his grandfather—contributed to the older man’s sense of well-being. For Lily, her father’s recovery contributed to her sense of healing.

“In addition to individual differences, there are robust cultural differences in how people consider their identities and personal boundaries and closeness, and interdependence. For example, U.S. and European countries are categorized to be high on individualism and independence and low on collectivism and interdependence, whereas most of the world are collectivistic,” said Lui. “People in more collectivistic cultures may have more fluid boundaries in how they conceive their own identity within the context of their relationships with their family members and ingroup members. My research has shown that Asian individuals such as Chinese are more prone than people from individualistic societies to think of their own success as a reflection of their family’s honor and shame, and think of themselves as a part of their cultural group and family.”

Responsibility and togetherness

Her father arrived for their cross-country trip a few days ago.

“It was important for him to have a goal,” she said.

And along the way, he mistakenly left his cane in a hotel.

So when he got off the plane, he was walking freely, without one.

Lily bought him another one, just in case.

Like other Asian American children, particularly those without siblings, she has a deep sense of responsibility for her father.

“I’m an only child,” she said. “If I don’t take care of him, who will?”

Added Lui, “Within these cultural values, people may be socialized to feel responsible for the well-being of their family members, especially elders. It is not uncommon for multiple generations of people in collectivistic cultures, including Chinese (American) and African (American) communities, to live in the same residence. The multigenerational travel and your friend’s appreciation for this opportunity do not surprise me.”

Mahlon can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.

Made possible in part by the Washington State Department of Health through a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This information does not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Washington State Department of Health or the Department of Health and Human Services.