By Mahlon Meyer

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

Over 100 people gathered on Fourth Avenue and Lenora Street on Sunday morning, the site of a fatal shooting of Eina Kwon and her unborn baby, while she sat in her car. The crowd, many members of which were burning with anger while others were flooded with feelings of helplessness, marched down to the site of the restaurant the dead woman had owned with her husband, Sung Kwon, who survived.

There were chants, and shouts, and expressions of outrage along the way. And when the crowd finally stopped outside the restaurant, speeches were given and even a bugle played. Elected officials showed up. And even fellow restaurant owners appeared. A huge outpouring of grief and anger and loss seemed to erupt beneath the rainy skies. Korean Americans who were present felt that they had been targeted for decades. Other Asian Americans saw this as another instance of a rising tide of violence against all Asian Americans. Even a Native American woman who cleans houses for formerly homeless people was there, seeing the loss of the dead Korean mother as another instance of six centuries of hate crimes.

At the end of the march, outside the Kwon’s restaurant, marchers listened to speeches. The crowd represented people with diverse backgrounds. (Photo by Mahlon Meyer)

But amidst the scrum of people and anger, flowing tears, and mouths set with fear, Xiaofu Hou (he declined to give his age, for fear of being tracked online) stood out like a flagstaff above a roaring sea.

For this man, Hou, had actually witnessed the whole thing—he saw the life leaving the body of Eina, 34, as she lay on the pavement with first responders working frantically to save her. Hou was in his apartment, which overlooks the intersection where the shooting took place. According to news reports, a homeless man has been accused of walking up to the car in which Kwon sat with her husband and opening fire.

“I heard gunshots, it was really loud,” said Hou.

He ran outside, onto his balcony, and began video recording the scene, in disbelief at what was happening—so that when belief caught up with memory, he would have proof that he hadn’t imagined it.

Pulling out his phone, he shared the video with the Northwest Asian Weekly.

His hand shaking as he grasped it, the phone showed the following scene:

Kwon lies on her back next to the open door of the white Lexus they were in. Both doors are open. Over her prostrate body, a dark suited man leans performing CPR. His regular thrusts at her chest have a quality of both desperation and helplessness, as if he knows she’s not going to make it.

She does not move the whole time.

In the background, her husband is restrained by an emergency worker. Wounded in the arm, he moves with frustration and helplessness, as he watches his wife dying under the frantic CPR thrusts.

At this moment, Hou spoke up.

“I can’t imagine what he must have been thinking or feeling at that moment,” he says. “Watching your wife die in front of you.”

Putting themselves in jeopardy

For the hundred-plus people who took part in the rally, it was almost as if they wanted to find out. An organizer told the Asian Weekly that the whole idea of meeting in the spot where the shooting took place was to put themselves in the line of fire, to experience the lack of safety and potential for death that everyone now faced, it seemed.

“The whole point is we can’t be afraid,” said Darren, who asked not to use his last name since he was there as a volunteer and not in a professional capacity.

For Susanna Keilman, 41, the primary organizer, the event was meant to signify the hollow promises and fake commitment of elected officials to the safety of Asian Americans.

Keilman, who ran for a seat in the legislature, but was defeated, said those who simply use hashtags such as “Stop Asian Hate,” and other slogans, without taking real action are just advertising what she calls false virtue.

Keilman may run again, but she says more can be done at the grassroots level.

Keilman was a medic in the Air Force, stationed in Korea, where her father was also in the Air Force, before working in pharmaceutical research. The fact that the shooter was Black was only relevant in that some in the Korean American community might remember rioting in Los Angeles in 1992 when primarily Black residents looted businesses of Korean Americans, an event to which she alluded.

“You can’t ignore the racial component of this given the history between the Black and Korean community,” she said. “But when you peel back the layers, it was a human that was enabled by poor policy to take the lives of other humans. This was preventable. We need to realize that everything our elected officials have done to provide solutions isn’t working.”

Immigrants in peril

But for Christine Bae, a professor in urban planning at the University of Washington, who was somberly observing the event, dressed in only jeans and a jean jacket under the steady cold drizzle, the event was the final reminder of a long line of attacks against Korean Americans.

“All immigrants come to America with a dream. And all immigrants are quite similar, starting with the Mayflower. They come with the hope to become grounded, to make a life and become healthy members of society and contribute to society,” she said in an interview in front of the many flowers laid along the storefront of the couple’s restaurant. “And, over and over again, Koreans are targeted.”

Peter Kwon (no relation), a Korean immigrant who is a city councilmember in SeaTac, said the rising wave of violence against all Asian Americans is alarming, not the least because while it skyrocketed during the pandemic, it is still increasing.

“The fact we have this gathering for a truly tragic event was tremendous,” he told the Northwest Asian Weekly. “But we should have had 1,000 people show up instead of somewhere over 100 people. Where is the community support? We should have seen more.”

As the crowd marched from the site of the shooting to the restaurant, about a half mile walk, many people fanned out, filling the streets, as bicycle policemen angrily shooed cars away and several police vehicles brought up the rear.

Marchers gather at the site of the shooting on June 17, 2023. SeaTac Councilmember Peter Kwon said they assembled quickly (Photo by Mahlon Meyer)

Faces were angry, bitter, and hopeless, as if the death of Kwon and her baby—who lived for a short time—represented the loss of something irretrievable.

“This is the same fight we have been waging for 600 years, since Christopher Columbus came and started wiping out people with a different skin color,” said Feanette Blackbear, 70, a member of the Lakota Tribe. She has lived in Seattle for 38 years, after moving from South Dakota.

Wearing a black mask that drooped around her chin, she said she was representing an organization that sought to find and recover missing and murdered indigenous women.

“The whole struggle is against the hate in our society,” she said.

Despite her long hours of housekeeping for Catholic Community Services, for people living in low-income housing, she came out to support the march.

“I was homeless for a year, so I know what it’s like,” she said.

A focal point for frustration and grief

The rally also served as a focal point for frustrations about crime and homelessness.

“Tragedies like this are a direct result of those on the city council that voted to defund the police, and never developed the alternatives to deal with drug and mental health issues they promised. We need a change of leadership and tackle real problems instead of promoting ideology,” said Gei Chan, C-ID Community Advocate.

Bae, who just moved to South Lake Union, said she had read an increasing number of “gruesome stories” in the newspaper. But now she is exposed to danger daily.

She saw the shooting as an escalation.

“I’ve seen people using drugs in the street in broad daylight. But now it’s come to the point of people killing people in broad daylight.”

Growing incensed, while the rain kept wetting her jean jacket and she grew wetter and wetter, she said, “The criminals walk the streets freely, and the innocent people are hiding from them.”

As one indication of how the city has changed, the site of the shooting was across the street from the once-famous Cinerama movie theater, where the first Star Wars movie opened in 1977, and crowds slept overnight on the streets, waiting to buy tickets.

At the same time, deep undertones of grief were expressed in the crowd.

As a member of the rally stood apart, playing a somber reveille on his bugle, people stood ashen and frozen, many crying openly.

Tanya Woo, a local business owner who is running for city council, said, “It’s absolutely heartbreaking to hear the news that a remarkable life and her baby were lost. Our prayers and thoughts go out to the Kwon family as they are dealing with this unimaginable tragedy. We feel this profound loss deeply. We stand in solidarity as our hearts are with the family.”

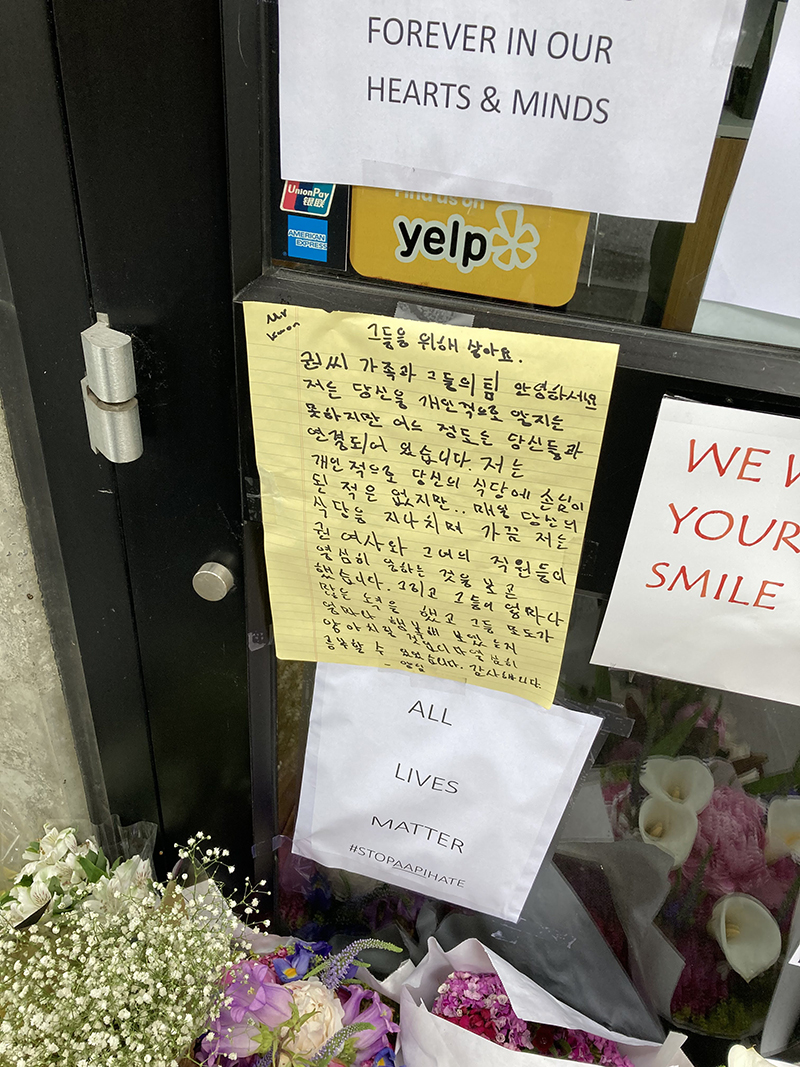

Even a note, pasted on the glass store front of the Keon’s restaurant, seemed to capture the sadness and surprise that two lives could so quickly be snuffed out, as easily as a candle flame, but lost forever.

“I was not your customer,” said the note, written in black marker, in Korean characters, which Bae translated for the Asian Weekly. “But I passed by your restaurant every day. I saw Mrs. Kwon working peacefully every day. I know you both worked so hard. You worked together so hard.”

Engaged and modest

According to Peter Kwon, who knew the couple through the Korean American Business Association, they were actively engaged in their very diverse neighborhood in SeaTac.

“They lived in a cul-de-sac with a very tightly knit community. I always saw them taking part in garage sales and chatting with their neighbors,” he said.

But the Kwons never tried to promote their restaurant among their neighbors, he said.

“Korean culture places a high importance on privacy, so they never even talked about their restaurant. They just talked about community issues.”

Peter Kwon is also the president of Asian Pacific American Municipal Officials, where one of the top priorities is seeking solutions to anti-Asian hate. Besides spreading awareness, encouraging neighbors to know each other, education also needs to be a focus, he said.

Formal education needs to address more directly diversity and issues of discrimination and its history.

“People learn about the world in grade school,” he said.

Moreover, the media needs to focus on positive stories involving Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

For instance, although Korean American Day is officially recognized at the federal and state levels, it took him a multi-year struggle to have it recognized in SeaTac. When the city finally proclaimed the day, it was generally not covered in the media.

The Kwon couple came, he said.

“There are lots of opportunities missed by the general media to celebrate the contributions of the AAPI community,” he said.

For Bae, the problem runs deeper. Decades of divisive economic and social policies have created a wasteland of divisions and violence.

“Our society should do more to improve everyone’s quality of life. Ethnic diversity and inclusion don’t happen just by talking about it,” she said.

Then, turning to the mass of flowers lining the storefront, she added, with bitterness, “We should be bringing flowers for some other reason—not because someone has died.”

The funeral service is scheduled for June 23 at 2 p.m. at Acacia Memorial Park, according to the Korean-American Association, Seattle.

Susanna Keilman requests that anyone wishing to make a donation to the family go to their GoFundMe page:

gofundme.com/f/helping-sungs-family-rebuilding-from-heartbreak

According to the Korean-American Association, Seattle, the Kwons have one surviving young son.

Mahlon can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.