By Kai Curry

Northwest Asian Weekly

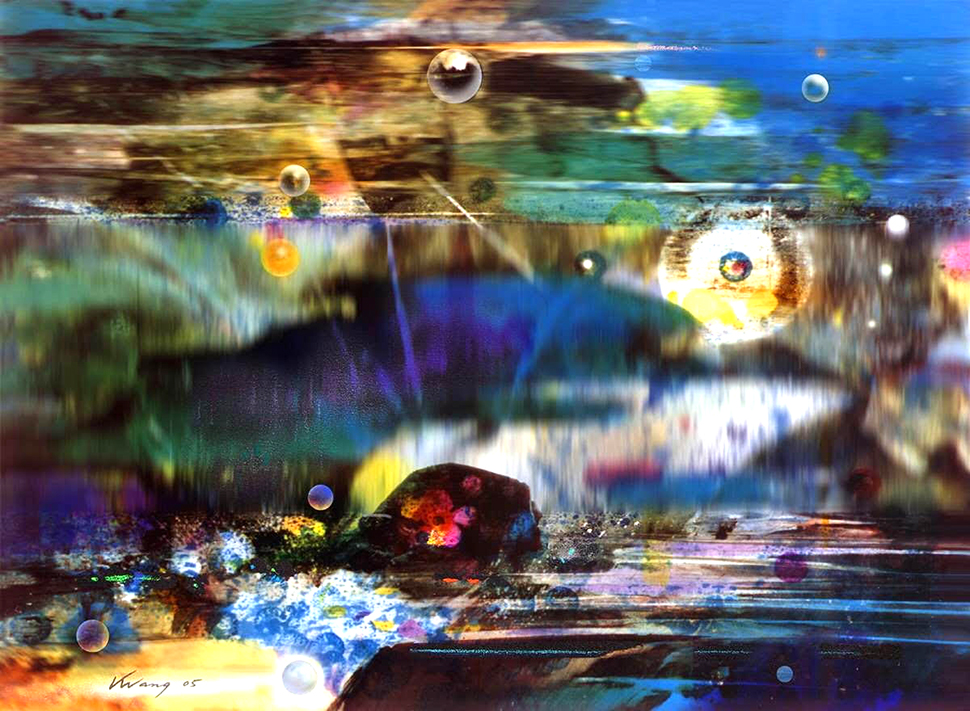

Victor Kai Wang using Chinese brushes with marking ink on Formica board. In the background is Victor’s painting, “Crystal Rainbow.” (Courtesy: Victor Kai Wang Family)

There are few artists who dedicate their lives to art. Serious art. Without significant pause,

Picasso comes to mind. Victor Kai Wang (汪凯) is another. Nothing stopped Victor from pursuing his art—not the Cultural Revolution in China. Not starting from scratch in Seattle.

“If you have your ‘why,’ you can endure almost any ‘how,’” said Victor’s older son, Will Wang Graylin, paraphrasing philosopher and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl.

Victor’s “why” is his passion for art, and its preciousness as a tool for expression.

“My father knew at a very early age…that he wanted to be an artist,” Will shared. “He followed his passion all the way up to last year, when he was 87,” at which point, Victor had a stroke. He is on the mend now, and finally retired, living with Will, in Boston.

“Enthusiasm: Hidden”, 1992, by Victor Kai Wang

Victor is like the Song literati painters of old, gentlemen scholars (文人) who, because of the vagaries of government, often faced exile. Since age 7, Victor followed his passion. His father, a bank president later persecuted to death as a “right wing” during the Cultural Revolution, found Victor the best teachers in Western and Chinese art. At 15, Victor got into the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts (GAFA) by lying about his age. And, no doubt, by talent.

In the same company as China’s greatest contemporary artists, Victor lived, breathed, and taught art. He married a talented ballerina, Diana, a half-American, half-Chinese who helped found the ballet schools in Shanghai and Guangdong. Life was good.

Victor worked hard—remarkably hard.

“He was essentially a representation of dedication to his craft,” Alvin W. Graylin, Victor’s younger son, recalled. In a documentary about Victor’s life, “Themes and Variations,” made by Will, Alvin described walking by his dad’s office at GAFA.

“He was always studying, always reading. You could see the shadow of him through the curtains.” Western art was not readily available in China at the time, so Victor painstakingly recreated the great art works of Europe so that he and his students could benefit. There were not many school books, so he made his own study guides, and translated English books into Chinese.

“Bow and Extend”, 1993, by Victor Kai Wang.

Then came the Cultural Revolution. Scholars were under pressure to adhere to Chairman Mao’s ideals. Often, their livelihoods were taken away. Diana found herself going from being a prominent ballerina who helped start Shanghai Ballet, one of the first in China trained by the Russians, to having her ballet school shut down. Due to the Wang (汪) family’s long history in China (their family tree goes back 94 generations to 605 BC and includes a Zhou dynasty royal) and Victor’s “right wing” banker father, Victor and Diana were designated for what was called “re-education,” as part of the Cultural Revolution.

When the couple and their 1-year-old son, Will, were sent to a labor camp in the countryside, they lived in a makeshift home converted from a chicken hut. Will notes in the documentary that his mother was labeled a “516 revolutionary” and incarcerated. She was released from prison only to give birth to Alvin. This caused Diana severe PTSD and led eventually to the breakup of her marriage with Victor a decade later.

Victor Kai Wang and wife Diana, and sons, Will and Alvin, during the Cultural Revolution when the family was reunited and allowed to stay at the same reeducation camp. According to VIctor’s sons, the bicycle was their only material possession. (Courtesy: Victor Kai Wang Family)

While in the camps, Victor was officially banned from creating art—yet he persevered, using rice sacks as canvas to paint when he was not working on the farm. Diana recalls in the documentary that Victor never saw their circumstances as a “mistreatment.” Instead, he used the opportunity to learn how to be a good farmer so he could “express the farmer’s life.”

Victor has always taken a pragmatic and optimistic approach to life and his responsibilities. In 1980, after the Cultural Revolution, Diana’s uncle and cousin helped sponsor the entire family to immigrate to Seattle, and Victor had to reorient himself again in a new land. He worked hard to support the family, dishwashing or painting storefront signs and windows, to afford a one-bedroom apartment and keep food on the table.

Like the Song painters, the reeducation camps were one form of exile. Coming to the United States was another form—but one that Victor and Diana chose to give their sons a better life.

When Diana’s PTSD flared up again shortly after arriving in the U.S. and she had to be hospitalized, Victor took on the responsibility of raising the boys on his own. Victor had some success in a color correction job at Yuen Lui studio. He got along with the owner and was able to use the cast aside photo paper, which he employed to devise a brand new technique, one based on his academic, traditional Chinese and Western training, but with new materials and a new visual aesthetic. He called it Marking Color.

The Weekly asked Will and Alvin what qualifies a person—their father—as a great artist. For Will, “It’s the lifelong pursuit and expressions driven by that sense of purpose for something greater than self, that beauty from the inside.” For Alvin, “A great artist is somebody who can bring a new form, a new medium, to life. And use that form to express himself and impact the viewer in a way that they haven’t seen before.”

Victor was never commercial. While he briefly had a gallery and sold his art, he rejected that path because he did not want to be bound to anyone else’s view of what he should paint—and he did not want to spend his time copying himself instead of innovating. When Alvin graduated college, Victor, a master calligrapher, gave him a painting of the word “Success” which, to Victor, has nothing to do with money and everything to do with beauty—inside you and around you. It is only recently that Victor is warming again—with the encouragement of his sons—to share his art in public. In the spirit of a traditional Chinese artist, he had always done so within the family, or by donating, but rarely by selling. You can see his work at the current Wing Luke “Reorient” exhibition, and hopefully, in the near future, through other in-person or digital means.

A great artist makes use of his heart and mind. His art makes you think, and also feel. From traditional Chinese landscapes to Western portraits, to abstraction in Marking Color, to a new method of photo and digital art he has been experimenting with that he calls “New Song”—Victor’s art incorporates all of this—and beauty.

In the documentary, Victor and Will sit on a bench on a Washington beach. They view a solitary tree, which inspired Victor’s painting, “Bow and Extend.” “Bow to the force of nature but don’t break,” Victor tells his son. “Continue to grow and extend.” Victor remarks on how the tree, like himself, “endures” in spite of the winds of change. “Most important is beauty,” says 汪凯. “If you want to make a beautiful painting, your heart must be beautiful inside. The painting outside shows the beauty. [But] this beauty comes not only from nature, but also from the human heart.”

Some of Victor Kai Wang’s work can be viewed at pinemoongallery.com/aboutus or at Wing Luke Museum’s “Reorient” exhibition (wingluke.org/exhibit-reorient). Will Wang Graylin’s documentary about Victor is at vimeo.com/manage/videos/172977552.

Kai can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.