By DONNA EDWARDS

Associated Press

Ingrid Yang’s future is laid out cleanly before her: Get her Ph.D., marry her fiancé, get a tenure-track teaching job and eventually retire and die of old age.

Her dissertation topic is, of course, the canonical Chinese American poet Xiao-Wen Chou—even though she’s Taiwanese American and has no real interest in his boring, straightforward style of verse.

But when a wrench is thrown into the equation, Ingrid’s life enters a disorienting spiral that brings her very self into question.

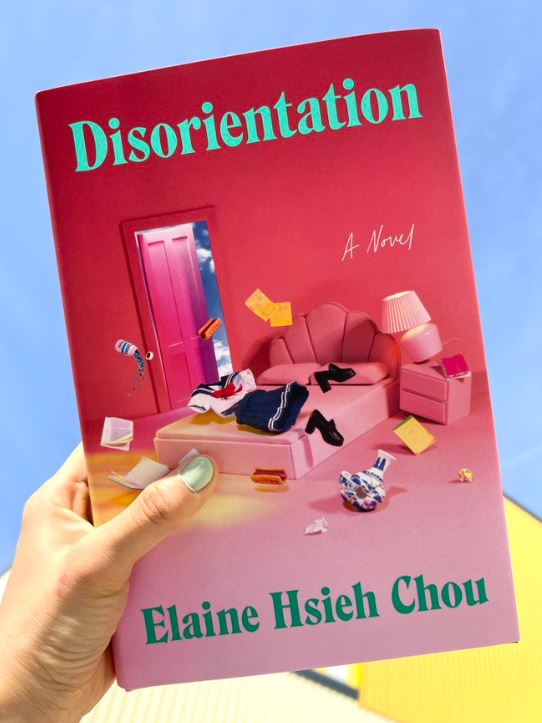

Elaine Hsieh Chou’s debut novel “Disorientation” is funny from the get-go, in the kind of humor that is uncomfortable and sits in that discomfort until you have to at least chuckle.

Take, for example, Ingrid’s fiance, Stephen. In the paragraph where he is formally introduced, the word “plain” is used six times, plus twice with near synonyms for plain, and finally he is likened to a sex offender when in the correct lighting. “But to Ingrid, he was perfect.” And, honestly, Chou makes a good case for it, which makes their relationship all the funnier.

OK, maybe not perfect. But nothing in Ingrid’s messy life is perfect. Her stress habits—like itching her eczema-stricken ankle and popping antacids and allergy pills like they’re illicit drugs—are increasing at an alarming rate. But when a mysterious note is left in the Xiao-Wen Chou archive, Ingrid believes she may have uncovered her ticket out of dissertation hell.

Though the story begins comically and simply, the mystery builds and the reveals are dramatic. As Ingrid solves more of the Xiao-Wen Chou puzzle, her world broadens and she begins to confront her often compliant—if not complicit—role in racism. Everything so carefully routine in Ingrid’s life begins to morph; her dissertation, her rivalry with Vivian Vo, her friendship with Eunice Kim, her engagement to Stephen, and ultimately her understanding of herself.

“Disorientation” satirizes academia, PC culture and every other topic it touches, bringing into question the very etymology of its title. Occasionally veering toward absurdity, the novel finds its way back to painful reality in a dizzying-yet-delightful oscillation. With chapter titles like “Chaos in the East Asian Studies Department,” Chou misses no chance to demurely poke fun.

The novel often dips into other genres, embedding college newsroom articles and TV interview transcripts. One such detour is an extended fever-dream courtroom scene, written script-style. It’s situational comedy, as wacky as an actual dream, but beneath the humorously bizarre veneer is a heart-rending analysis of Ingrid’s love life, complete with repressed memories, shame, bitter self-reflection, and a comprehensive list of movies that portray Asian women in a problematic way from the past 100 years.

Though you would never know it from how fun this wild ride is, “Disorientation” is a seminar bursting with lessons on race, gender and culture, complete with a bibliographical Notes section and everything. Chou clearly did her research.