By Jason Cruz

Northwest Asian Weekly

The Northwest Nikkei Museum and the Japanese Cultural & Community Center of Washington hosted a Speaker Series in September which highlighted the past accomplishments of Nikkei pioneers in sports. The rich history of sports clubs established by Japanese Americans reflects its strong community ties.

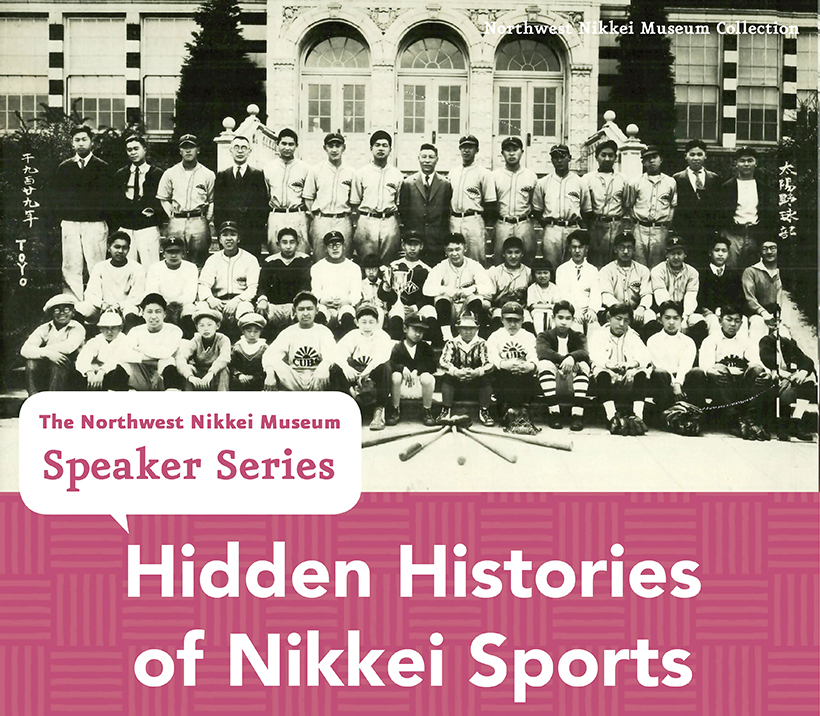

Entitled “Hidden Histories of Nikkei Sports,” the Zoom talk educated participants of the robust accomplishments of Japanese history. There were three representatives from three different organizations, each with a different story.

The first presentation discussed the Rokka Ski Club. The club started in 1936 by an individual who loved to ski and wanted to share his experience with others. Rokka, which means six-sided snowflake in Japanese, disbanded during World War II. After the war, there was renewed interest in skiing again and the club was reformed in 1950. In 1959, the Rokka Ski School was created to help those wanting to join but not knowing how to properly ski. They joined the Professional Ski Instructors Association in 1961 to become certified instructors. The organization had about 600 members, offering three buses each to Snoqualmie and Crystal Mountains.

In 1993, Rokka started teaching lessons in the Japanese language. To this day, Rokka still teaches in Japanese and English.

On behalf of Rokka, Nancy Kitano’s family had been skiing with the club for a total of over 50 years.

“One of the great things about Rokka is that you join and it’s a big family,” Kitano explained. The organization currently operates at the Summit at Snoqualmie at Summit West, teaching from age 5 up to adults. Kitano became a ski instructor for Rokka. All of the instructors are volunteers and do it out of love for the sport.

“One of the cool things that I’ve enjoyed is watching our students start at the age of 5 floundering around…and eventually grow up to become our new instructors.” At the end of each season, there are special training sessions to help cultivate the next generation of ski instructors.

In addition to their winter activities, Rokka holds bike rides and a golf tournament during the summer.

The second presentation featured Masaru Tahara who spoke about the Tango Club, a fishing club, which began in the 1930s. Tahara wrote a book about the club entitled, “Tengu – Tales Told by Fishermen & Women of the Tengu Club of Seattle.” The club was established due in part to fishing competitions (known as derbies), excluding people of color from the events. Tahara discussed how Japanese Americans were experienced in both freshwater and saltwater fishing. Membership was around 240-250 individuals participating in this “practical and enjoyable sport.”

However, the club abruptly ended on Dec. 7, 1941, the date of the attacks on Pearl Harbor.

After World War II, Tengu Club was re-established in November 1946 with a fishing derby. Many people joined the club after returning from internment camps.

“The social environment was still not kind to them,” Tahara said of the first fishing derby after the war, “Surprisingly, 172 people showed up.”

In the 1940s and 1950s, the Seattle Times held salmon fishing derbies in which nine Nikkei members of the Tengu Club won prizes. Despite the anti-Japanese sentiment post-World War II, the organization prided itself on including all races and genders participating in club activities.

The final presentation included Kerry Yo Nakagawa of the Nisei Baseball Research Project. He discussed Nikkei Baseball in the Northwest.

“I feel it’s a hidden legacy and amazing treasure,” said Nakagawa. He discussed Frank Fukuda, who was one of the first pioneers of Japanese American Baseball. His teams toured Japan and showed the ‘American style’ of baseball to Japan.

In 1914, Fukuda and his team toured Japan and went on a 42-day tour playing different teams. Nakagawa stated that the team wanted to observe the Japanese culture and community. He noted that Fukuda wanted to mesh the Japanese culture with the American culture, identifying the need to learn their Japanese heritage and customs. Not only did a Seattle team go to Japan, but other teams from Los Angeles, Alameda, Fresno, and Stockton, California went on tours of the country and became ambassadors of the sport.

Nakagawa’s organization preserves the history of Japanese American Baseball through pictures and memorabilia.

During the talk, Nakawawa displayed several old pictures of Fukuda and his traveling team of baseball players as they traveled from exhibition to exhibition.

All of the presenters detailed in their presentations and pictorials the strong sense of community through the experience of a sport/hobby that Japanese Americans felt passionate about. Through these activities, the participants felt more of a sense of identity and inclusion.

For more information on Rokka, visit rokkaski.com.

For more information on the Nisei Baseball Research Project, visit niseibaseball.com.

Jason can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.