By Kai Curry

Northwest Asian Weekly

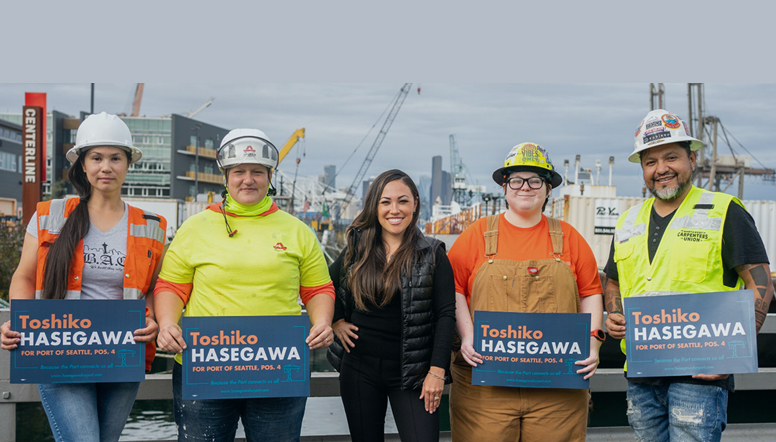

Toshiko Hasegawa (middle) with Port workers (Photo from hasegawaforport.com)

She is the same firecracker who took the helm of the Washington State Commission of Asian and Pacific American Affairs (CAPAA) in 2018. The same daughter of union activists. The same proud woman of color. Now aiming her sights at the Commissioner Position 4 seat at the Port of Seattle election in November, Toshiko Grace Hasegawa has a vision of what the future of the Port can and should be. It’s a vision she thinks is overdue and has been overlooked by Port officials, so far.

According to Hasegawa, this position with the Port “touches everybody in their daily lives, from consumers to businesses to workers to commuters to passengers. It is the fourth largest container port in the nation and equidistant between Asia and Europe, so it’s a point of entry for goods and people around the world.” The Port is “considered to be the economic engine of our region” and it is one of the “largest polluters of carbon emissions in our state.” All of these are reasons why Hasegawa wishes to take on the job, with the fact that she grew up on Beacon Hill, a Port-side neighborhood, and has a close, historical connection to this hub of industry and transportation.

“My family’s American story begins at the Port of Seattle when my great grandparents immigrated by boat in search of economic opportunity,” Hasegawa told the Weekly. “They put down roots in Beacon Hill because it was one of the only neighborhoods they were allowed to live in, due to the exclusionary redlining laws.” It is this type of inequity, lived by people of color, immigrants, blue collar laborers, that has been rife, too, in some Port of Seattle operations—and in industries still run primarily by white males—which Hasegawa intends to combat and change.

People who live near the Port of Seattle, which includes Sea-Tac Airport, have been victims of “higher incidence of infant mortality, lower life expectancy, higher incidence of asthma and cancer, and even disparate educational outcomes,” Hasegawa said. “All of these things are directly connected to increased exposure to pollution. I’m running because the Port of Seattle has a tremendous role to play in answering to the environmental and public health challenges of our time.”

These concerns, along with growing infrastructure problems, have not been approached properly by Port officials, in Hasegawa’s view. She cited specific examples, such as the recent re-designation of Terminal 46 for cruise ships instead of loading and unloading cargo ships, at a time when supply chains are at a breaking point.

“Ships are backlogged in the harbor waiting to unload…they are hanging out in the islands, destroying quality of life.” Hasegawa shared a story of a boba tea shop owner worried about going out of business due to not receiving her inventory. “Shipping had its best year on record due to COVID-19” and rather than blaming COVID-19 for the current backlog, Hasegawa said, “We should have known that this was a priority.”

Hasegawa elaborated on plans to replace North Sea-Tac Park with a parking lot or warehouse, which she says her opponent, Peter Steinbrueck, supported—although she says he has denied it.

“He approved the sustainable airport master plan, which proposed clearing acres of forested land for a staff parking lot.” According to Hasegawa, “Even if they say they’re fighting against developing North Sea-Tac Park, they approved the real estate strategic plan…they don’t have the lens necessary to know that this…causes harm to community members [and] are not honoring the community’s cause of wanting to invest in and preserve our precious green spaces.”

Hasegawa continued, “It is vital to have recreational green space, vital to our natural ecosystem. It neutralizes carbon emissions that are particularly impacting Port-adjacent communities and local wildlife.” She suggested that Port officials have rubber stamped, harmful proposals without taking into account greater environmental and quality of life issues. “Rebuilding our economy and reducing pollution are two goals that go hand in hand. Historically, these two interests have been pitted against each other, but if we do it right, we can have our cake and eat it, too.”

If she wins, Hasegawa will be the first woman of color commissioner at the Port of Seattle. Her plans are both futuristic and feasible. She wants to expand electric rail to connect terminals, expedite flow of goods, and address poor working conditions of truck drivers sitting in “four-hour-long work lines” or taxi drivers stuck in traffic. She proposes offshore windmills “to sustain our future way of life, where we abandon the fossil fuel paradigm and step into sustainable renewable resources,” and more apprenticeship opportunities to teach workers the skills they will need in this greener economy. She intends to partner with all levels of government, as well as nonprofits, so that “all people have the opportunity to access opportunities at the Port.”

Through CAPAA, and a life of activism, Hasegawa believes she has “demonstrated history of doing systemic reviews at the state and county level, providing feedback in order to build systems of accountability to promote transparency and integrity in government operations.” She is a fighter. As a child, she attended union rallies with her parents, and now she takes her own 9-month-old daughter, Keiko Rose, to marches and protests with her.

“The reason why I’m in a position to run for office is because someone before me spoke out and advocated for my rights and it’s my job to pay that forward for a better future,” Hasegawa said. “There are two things that can stand against the influence of big money: people power, the power of numbers united for a common cause; and your vote—democracy. It’s not just your right to do these things to fight for a better future, it’s your responsibility.”

Kai can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.