By Samantha Pak

Northwest Asian Weekly

Afterparties

Afterparties

By Anthony Veasna So

Ecco, 2021

A high school badminton coach past his prime tries to beat his team’s star player at the game. A mother and her two teenage daughters work at their 24-hour donut shop. Two drunk brothers at a wedding afterparty try to expose their uncle for snubbing the bride and groom. A young boy learns his mother survived a racist mass shooting at her elementary school. These are just a few of the characters included in So’s collection of short stories, “Afterparties.”

Taking place within the same Cambodian American community in an unnamed city in California, So gives readers an intimate glimpse into a group we’ve rarely seen on the page. Up until now, stories about the Khmer experience in the United States have been almost exclusively about the Khmer Rouge—and that’s when those stories even get told at all.

What is refreshing about So’s stories is that he shows there’s more to Cambodians than surviving a genocide. That trauma may be in the background, but that’s not the only thing that defines his characters, who are the children of refugees. They’re queer, flawed, and messy, foul-mouthed and have their own dreams and ambitions. So does a great job of balancing the serious with the light hearted that makes up a generation of young people doing their best to carve a path for themselves after their elders have survived so much hardship. One thing I especially appreciated was how none of them fell into the second-generation trope of being ashamed of their roots. They never wanted to be anything but Khmer—struggles and all.

As a Cambodian American, I may relate to the AAPI characters I read in the stories for this column in a broader sense, but this was the first time I’ve seen specific experiences and references on the page that might as well have been pulled from my life. From the older generation giving the main characters grief and the insistence that there’s a difference between being Chinese and Chinese Cambodian (because there is), to Hennessy being the liquor of choice and beef sticks as standard fare at every Cambodian gathering, I have never felt so seen in literature.

A Thousand Beginnings and Endings

A Thousand Beginnings and Endings

Edited by Ellen Oh and Elise Chapman

Greenwillow Books, 2018

Every culture has its own fairy tales and folklore. From star-crossed lovers and meddling immortals, to feigned identities, battles of wits, and dire beginnings, Asian cultures are no different.

In “A Thousand Beginnings and Endings,” we get a collection of 15 short stories from 15 authors who have reimagined myths and legends from various Asian cultures, including Chinese, Hmong, Vietnamese, Punjabi, Filipino, and Japanese.

A mountain falls in love with a mortal man. A teenager suspects her father has been replaced by an android. A young woman follows in her mother’s footsteps to help ghosts cross over to their final resting place.

In these retellings, the authors have taken the originals—whether they’re actual stories or just cultural traditions—and added their personal twists. Some even reflect their personal backgrounds, which was fun to read. I also appreciated the variety of genres explored in this collection, which ranged from science fiction and fantasy, to contemporary and romance.

I love a good retelling of the classics, and “Beginnings and Endings” is no exception. And while retellings of Western fairy tales like “Cinderella” and “Snow White,” as well as classics from Shakespeare and Jane Austen, are plentiful, it was refreshing to read a collection of reimagined stories from different cultures—especially cultures whose folklore may not get much attention in the Western world. The tales may be different from what we’re familiar with, and there’s not always a happily ever after, but that’s okay.

Like any good myth or legend, the stories often serve as lessons we can apply to our own lives.

Following each story is a brief note from the author explaining the source material and sometimes, their own personal connections to the tales. Not only does this collection introduce readers to these cultures and their mythologies, but in some cases, they’re also introducing readers to authors they probably haven’t read before.

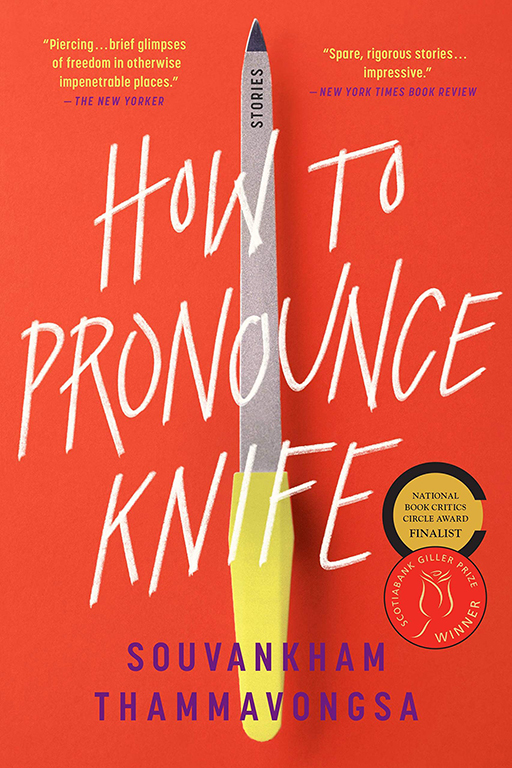

How to Pronounce Knife: Stories

How to Pronounce Knife: Stories

By Souvankham Thammavongsa

Little, Brown and Company, 2020

Two siblings discover the joys of trick-or-treating. An ex-boxer starts working at his sister’s nail salon. A woman grows obsessed with country singer Randy Travis. A young girl and her best friend imagine what it would be like to be rich.

These are just a few of the characters in Thammavongsa’s collection of short stories. Despite being in different stages of life and different life circumstances, they all have a few things in common. As they move through life, amidst their disappointments, acts of defiance, and love affairs, readers see their hopes and their desire to just find a place to belong.

Thammavongsa’s characters reflect her Laotian background—a culture, despite its proximity to my own heritage, I don’t know much about (and I’m sure I’m not the only one). She doesn’t delve too deeply into the Laotian American experience, but does occasionally make references to the characters being refugees and trying to establish a life in their new country. While I would have liked to see more specificity in this regard, I appreciated Thammavongsa’s narrow focus on each of the individual protagonists in her stories. In doing this, she makes them more relatable—whether they’re school-aged children or senior citizens—showing readers that they’re not any different from the rest of us.

Thammavongsa’s language is fairly minimal, but it doesn’t feel like anything is missing from her stories. If anything, it actually adds to the intimacy we feel as readers, with the characters. We feel as if we know them already and have a shorthand with them like we do with those we are closest with.

Samantha can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.