By Andrew Hamlin

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

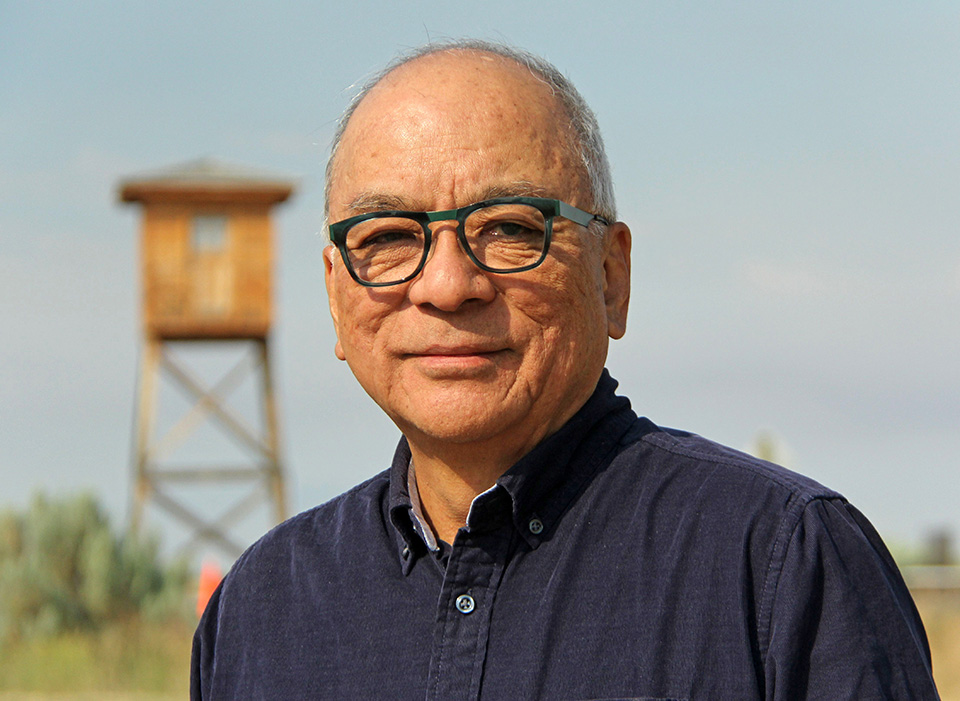

Frank Abe (Photo by Eugene Tagawa)

The incarceration of Japanese Americans in concentration camps during World War II is in itself no secret. But as writer Tamiko Nimura asserted about her work on a new graphic novel of the camps, “I’m hoping that people inside and outside the Japanese American community will see that the story of camp is incomplete without the story of resistance.”

The new book, “We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration,” features all-local talent—written by Nimura with Frank Abe, and illustrated by Ross Ishikawa and Matt Sasaki. It’s published by the Wing Luke Museum in collaboration with Seattle’s Chin Music Press.

Veterans in Maynard Alley in front of old Wah Mee Club. Illustration by Ross Ishikawa.

Three of the four contributors—Abe, Nimura, and Ishikawa—will join Tom Ikeda from Seattle’s Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project, for an online discussion, at 6 p.m. on June 14. Registration is at eventbrite.com/e/we-hereby-refuse-book-event-tickets-152224693155.

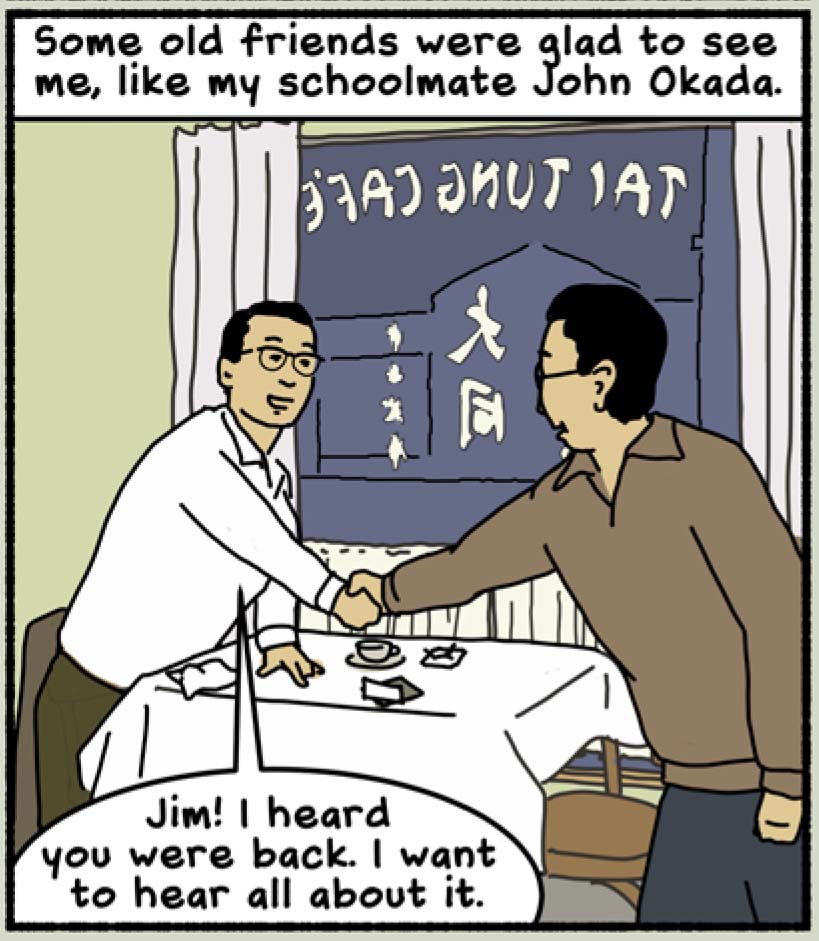

The narrative weaves together three crucial stories of resistance in the camp communities. Jim Akutsu refused to be drafted out of the Minidoka camp in Idaho, then got classified by the government as an enemy alien—his story inspired John Okada’s classic novel “No-No Boy.” Hiroshi Kawshiwagi, interned at Tule Lake, California, refused to sign a loyalty oath to America and ended up renouncing his citizenship. Mitsuye Endo, interned at Topaz, Utah, became party to a lawsuit against the internment process, which went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“The Wing Luke had the initial vision” for the project, Abe explained. “The mission…is to connect everyone to Asian American history through vivid storytelling. They grasped the power of the graphic novel to bring together art and history in a personally engaging way… The format is accessible to readers of all ages.

Illustration by Ross Ishikawa.

“They got an NPS (National Park Service) Confinement Sites Grant for a series of three graphic novels, of which this is the second, and the four of us answered the call for proposals.”

The book was a collaborative process, but Nimura worked the most on Kashiwagi and Mitsuye Endo’s stories, with a sideline on the Mothers’ Society of Minidoka. In her case, a personal connection was a big help.

“Hiroshi Kashiwagi is my uncle, and I edited his first two books, so I naturally felt drawn to working on his story,” she explained. “I wanted to work on women’s stories of resistance, so Endo’s story and the Mothers’ story were compelling for me””

Ishikawa illustrated the Akutsu and Endo stories, plus side stories on the U.S. government, and the machinations of the Japanese American Citizens League.

“I think Matt’s style lent itself well to the more visceral situations at Tule Lake,” he explained, “while the stories I worked on depended more on character interplay and emotional dynamics.”

Abe, from his writer’s perspective, characterized Ishikawa’s artwork as expressive, and Sasaki’s as expressionistic. But he allowed that they “both did an exceptional job.”

Illustration by Ross Ishikawa.

The contributors hope that the project will help humanize the story of the camp, and bring readers to the subtlety and emotional nuance of such historical figures. But they acknowledge that the political and cultural urgency of the story remains with us, more than seven decades later.

“The same elements of fear and ignorance of the ‘other’ that open the book are present today,” Abe asserted. “This book opens with the FBI knocking on the door to arrest Jim Akutsu’s father, and it ends with ICE breaking down the door to deport immigrants. This book opens with government officials gaslighting groundless claims of Fifth Column activity among the Japanese on the West Coast and Hawaii, as a pretext for mass expulsion and incarceration. Just one year ago, we had a president who dog-whistled ‘China virus’ and ‘Kung flu’ and unleashed the random terrorism against Asian Americans on the streets today.

“The only way to undo this is to show Asian Americans as real people to those who still don’t get it. It’s books like ours that create empathy.”

Andrew can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.