By Samantha Pak

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

Paula Yoo (Photo by Sonya Sones)

When Paula Yoo accepted a job at the Detroit News in 1993, her friends asked her if she was scared.

It had been 11 years since the murder of Vincent Chin, but his name was still spoken among her fellow Asian American journalists.

In 1982, two white men killed Chin while he was out for his bachelor party. This was during a time when anti-Asian sentiments were particularly high. The influx of Japanese cars at the time hit the American auto industry hard and the men who beat Chin to death, Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz, were a Chrysler plant supervisor and laid-off autoworker, respectively. They allegedly assumed Chin—who was Chinese American—was of Japanese descent, used racial slurs when they attacked him, and blamed him for the success of Japan’s auto industry. Ebens and Nitz ended up pleading guilty to manslaughter and receiving only a $3,000 fine and three years’ probation.

“I was a little nervous,” Yoo said about moving to the Motor City. In addition to being Korean American, Yoo, who lived and worked in Detroit for two years, also drove a Nissan at the time—a Japanese car, although hers was made in the United States.

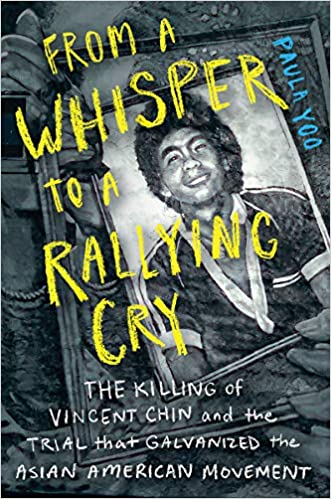

Even though she arrived in Detroit more than a decade after Chin’s murder, Yoo was always interested in his story. That interest has culminated in her new book, “From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry: The Killing of Vincent Chin and the Trial that Galvanized the Asian American Movement,” the first-ever full-length book to tell the story around the case.

The book comes out April 20 and is an extensively researched account of Chin’s murder, the trial and verdicts, and the outrage sparked by Ebens’ and Nitz’s lenient sentences. That outrage led to protests and a federal civil rights trial—the first involving a crime against an Asian American—and galvanized what became known as the Asian American movement.

“From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry” is categorized as young adult nonfiction, but Yoo said her reporting in the book would be no different if she had written the story for the New York Times.

This being said, the “spine” of the book is a young man named Jared, whose mother was engaged to Chin. Short vignettes featuring Jared and his coming-of-age journey as he unearths his connection to Chin are sprinkled between each of the book’s six sections.

Heartbreaking research

While Yoo has put down her reporter’s notebook, her journalism background has helped her as an author (fiction and no-fiction), TV writer/producer, and feature screenwriter. She has a tendency to overreport and underwrite.

“You can take the girl out of the newspaper but you can’t take the newspaper out of the girl,” she said, adding that by leaving no stone unturned, she knows she can stand by her work and be confident that what she writes is authentic and accurate—even in a genre such as science fiction, in which anything can happen, her writing is grounded in a reality that makes sense in that universe.

No one can truly be objective on a topic, but Yoo believes it is possible to be fair. And that was her goal with “From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry.” Her over researching—or “Yoo diligence” as her friends call it—is evident as she combed through court transcripts and contemporary news accounts and interviewed people from all aspects of the case—not just the attorneys (on both sides) and those close to Chin, but others such as the activists who protested after the sentencing and the emergency room nurse who treated him. Yoo wants readers to read the story, with all the evidence she’s presented, and like a trial jury, come up with their own conclusions on the case.

The only place in the book where readers learn Yoo’s personal opinion on the case is in the afterword.

As thorough as she was with her research, Yoo said it was also heartbreaking because everyone she spoke with cried or at least teared up during their interviews.

“They’ve had to live with this trauma for so long,” she said. “They were reliving it.”

Yoo was also able to speak with one of Chin’s killers, Ebens, for an off-the-record conversation.

“I cried in the car afterwards,” she said, adding that she was grateful he let her in because Ebens didn’t have to.

Justice versus legal accuracy

“From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry” has taught Yoo that compassion and justice are not mutually exclusive. You can be compassionate toward a perpetrator and still be angry that justice had not been served, she said.

Yoo also learned that there’s a difference between justice and being legally accurate to the letter.

This was another legacy of Chin’s case. It revealed flaws in the justice system. Now in Michigan, prosecutors are required to be present at hearings for manslaughter cases. They hadn’t been prior and with Michigan formerly nicknamed the murder capital of the nation, the sheer volume of cases made it physically impossible for them to attend all of their hearings. And in the case of Chin’s murder trial, Yoo said this led the judge to make a decision based on limited information, but was still considered legally sound.

History repeating itself

History repeating itself

When Yoo was in her 20s, she realized how little she had learned about Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) history and so she went to the bookstore to supplement her incomplete education. This is one of the reasons her other writing includes nonfiction children’s stories about historical AAPI figures.

“These books need to be taught in schools,” she said, adding that they’re especially needed to wake up non-AAPIs to the racism and micro and macro aggressions AAPIs have experienced and are still experiencing.

The parallels between Chin’s murder and the rise of anti-AAPI hate and violence amid the pandemic is not lost on Yoo. She said what happened to the auto industry in Detroit was terrible—people lost their jobs and suffered great financial losses. But that did not excuse ignorant people trying to find Asian faces for scapegoats—just as it doesn’t excuse people nowadays blaming AAPIs for COVID-19.

“It’s so infuriating,” she said. “It breaks my heart that young people today are not surprised (at the rise in anti-AAPI hate and violence).”

As a member of Generation X, Yoo said her younger self was optimistic that things would change as she got older. She doesn’t want to be cynical, choosing to view the glass as half full. But she can’t help express her frustration at how long society has to go in terms of racial equity and justice.

“It’s getting harder and harder to ignore the empty air in the glass,” she admits.

A legacy of solidarity

Chin’s murder may have been a battle loss, but Yoo said AAPIs have not yet lost the war for racial equity and justice.

Just as the AAPIs are speaking out against the violence and hate the community is currently experiencing, people made their voices heard in the aftermath of Chin’s murder as well.

Included in these fights has been support from other groups. And this solidarity of different communities coming together to fight white supremacy and systemic racism needs to be celebrated. In her research for “From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry,” Yoo learned how the Black and Latinx communities, as well as churches and synagogues, stood with AAPIs in their fight for justice—just as they stand with AAPIs today.

“It was so inspiring to see,” Yoo said.

Samantha can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.