By Kai Curry

Northwest Asian Weekly

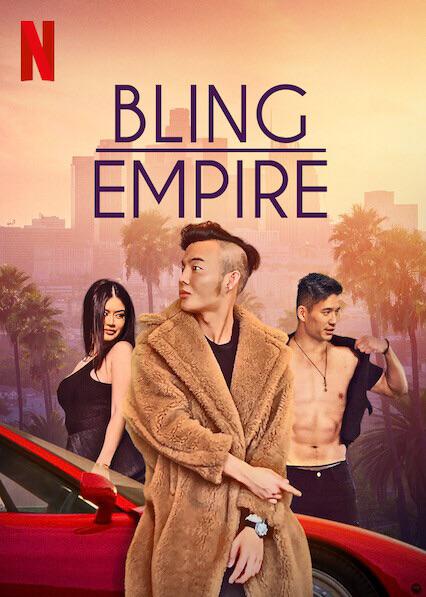

Photo courtesy of Netflix

Netflix has been receiving a lot of criticism lately for its lineup. No less “Bling Empire,” which premiered Jan. 15. An Asian version of the Kardashians, this reality television series has been slammed for being racist and thrown in with the movie, “Crazy Rich Asians,” as an unfortunate trend of Hollywood depicting Asians and Asian Americans only as rich people behaving badly. The question out there is if this is the type of celebrity AAPIs wanted? I argue there are a lot of types of shows out there and this is just one of them. It’s the price of fame.

Yes, from advertising, the trailer, and even if you stuck to the first episode, you might surmise “Bling Empire” consists of stereotypes, racism, and rampant fakeness. The premise of the show is that “crazy rich Asians” are real (didn’t Kevin Kwan tell us that?) and that a few of these crazy rich Asians live in Los Angeles. It’s set up as a tribal thing right away. A tribe of richness and Asian-ness. They all know each other. They don’t fight, fibs Kane Lim, child of an oil and shopping mall dynasty, living in the U.S. to escape responsibility across the pond. They are party animals that use money as one way to buy happiness, suggests Christine Chiu, who is not shy to tell us her husband is descended from a Song emperor. There are all the accoutrements in the show you would expect—limousines, rollicking nightlife, and plastic surgery. There is bling.

But once you get deeper into the show, not only is it difficult to find anything riotously offensive, but it’s also difficult to say there aren’t redeemable qualities.

Weapons heiress Anna Shay (left) attends Christine Chiu’s Chinese New Year celebration on Rodeo Drive. (Photo courtesy of Netflix)

True, there’s a lot of gratuitous showing off of beautiful bodies and beautiful clothes. There are way too many tiaras. There are occasional tacky comments peppered in, mainly by Kane, such as, “Are you calling me fat? Prosperous. That’s what we call it in Mandarin,” or that Chinese people are good at math—possibly the most un-PC statement in the entire first season and even he sounds uninvested in it.

Kane Lim in front of his shoe collection. (Photo courtesy of Netflix)

There are also true explanations, such as that people from Asian countries like to remove their shoes at the door and wear house slippers. Or that Asian societies pressure women to bear male children. If anyone is stereotyped, it’s rich people.

Kelly Mi Li and her “Latin lover”, Andrew, have a tumultuous relationship. (Photo courtesy of Netflix)

Or Kelly’s “passionate Latin lover,” Andrew. Saying things like Chinese New Year is better than “white new year” because you get money seems like what an Asian might really say. Maybe the problem for some is having these inside jokes exposed. For the most part, the cast of “Bling Empire” is pretty normal, and I assert most of them are not even crazy rich. They shop for themselves. They have immigration stories, non-traditional families, and working mothers. I’m positive Eleanor Young would not approve.

Early claims have been that “Bling Empire” is unrelatable to most people, yet that’s not really the case. Income-wise, maybe. But the show has a soft side, which might keep audiences coming back. At first, the most awkward member of the tribe is newcomer Kevin Kreider, who professes that he likes being around other Asians, because when he was in Philadelphia, he stood out as one of the only Asians people knew.

But Kreider is not exactly a “regular guy”—he’s a model. And he’s adopted. He’s never been to a Chinese New Year party. He has a hard time being related to by anyone. Yet his quest to be accepted and learn more about himself is endearing and human. So, too, is DJ Kim Lee’s search for her real father, Kelly’s fears about whether or not Andrew really loves her, and Christine’s hesitation about having more children.

The characters divulge vulnerabilities about their pasts and their relationships that provide an endearing counterpoint to the flash and frivolity of the rest of their lives. At first, I suspected that the inclusion of one of the most outrageous characters, Anna Shay, a half-Russian, half-Japanese weapons heiress (yes, that’s a stereotype), could be racist in that she, the part-European with dyed blonde hair, often plays the foil to others when they are acting immature or inconsiderate. But after a while, the tribe coalesces satisfyingly, and they all hold their own.

Some have complained that they can’t tell if the show is real or fake. I would ask how is this new to the genre? It could be the complaints are really about reality TV shows, not this particular reality TV show. Is how the people are portrayed “true”? I don’t know. Are the Kardashians true? Critics have said, too, that they don’t want to see only rich Asians portrayed on the screen. The big question being: Is this the type of Hollywood exposure that AAPIs wanted? Have AAPIs “made it” because they get their own reality show? I would add, “like everyone else?”

For better or for worse, viewers like gawking at rich people. The fact that they want to gawk at Asian rich people is, in a way, a compliment. There are TV shows and movies out there that depict “regular” AAPIs, such as Apple’s effort at diversity with Little America or Kim’s Convenience, about Korean grocers, also on Netflix.

There is Awkwafina visiting her dying grandmother in The Farewell. And Randall Park, playing a guy who works in air conditioning and raps in a neighborhood band in “Always Be My Maybe.” Normal and relatable get an indie award and pulled from the lineup because no one is watching. Sensationalism and extravagance get views.

Tacky comments said by someone who is Asian himself seem to hint at insecurities he might have about his own position in the world, rather than make “Bling Empire” a racist show. People behaving extravagantly, or just being annoying, is not racist, though it could be a stereotype of the LA rich. Yes, it is worrying that the people on the show might be taken as the standard for all AAPIs and spark racism from non-Asians and have-nots because the participants are frivolous and rich.

Those haters are not the people who are going to look deeply anyway. In fact, there is a lot to connect with in “Bling Empire,” and a lot to help make AAPIs relatable to those who, like Kevin, haven’t spent enough time in their company.

There are other shows out there but shows like “Bling Empire” get attention. It is a product of an industry that feeds the market what it wants. What the public can do is urge Hollywood, and everyone, to keep exploring, keep storytelling, and keep including. The release of “Crazy Rich Asians” was celebrated as a good thing. Now “Bling Empire” is being accused of being too much. Asking for equal exposure, yet only wanting to expose the bits you like, is not fair. If AAPIs want to go mainstream, it’s going to include reality TV—and that could be a good thing, too.

Kai can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.