By Mahlon Meyer

Northwest Asian Weekly

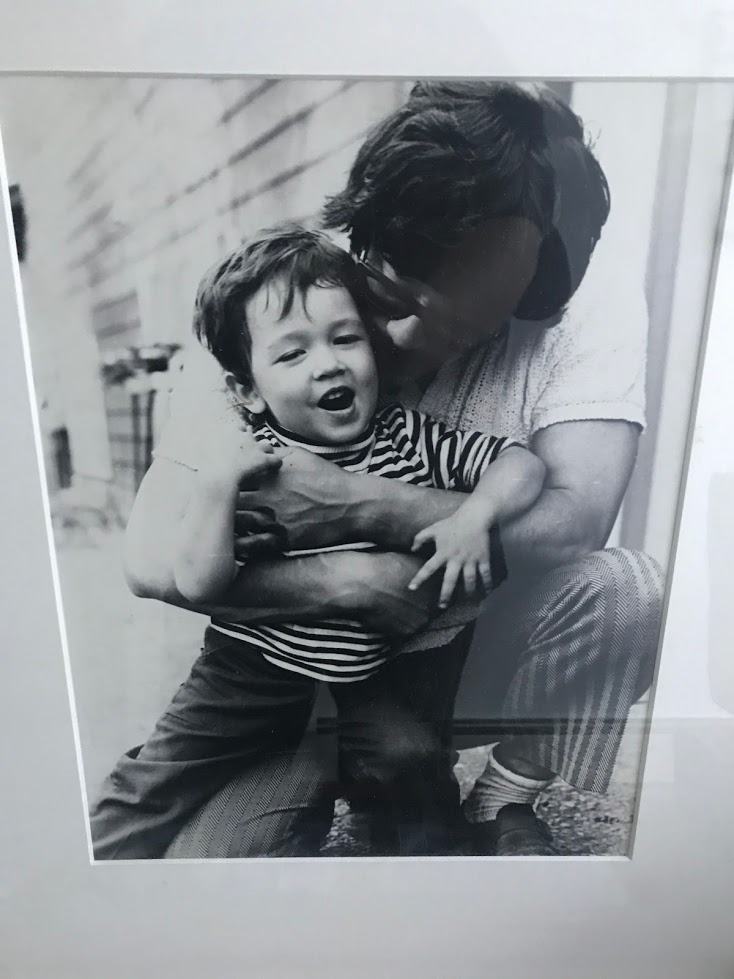

Taky Kimura with his young son, Andy

Giving a speech in 1994, Taky Kimura looked at his son. His son had just reached across the table for a pitcher of water. Kimura, the most prominent disciple of Bruce Lee, stared at his son sternly as if he had just launched a punch. But when his son poured a glass full of water and handed it to Kimura, he went on with his speech.

It was a small gesture, but it summed up a life of betrayals and vigilance, even by his own people—if he could figure out who they were.

Kimura’s life was spent searching for a tribe of his own, which he found in the martial arts community he fostered and grew. Now 96 and battling with dementia, his son is continuing the journey.

In interviews with Northwest Asian Weekly, Kimura’s students, his son, and others helped piece together a life of searching, devotion, and hard work.

In the video of Kimura’s speech, given in England 26 years ago, he outlined the trajectory of his life.

Kimura was born in 1924 in Clallam Bay. When he was growing up, his family was the only non-white residents of the town.

“I thought I was white until I was 15, but my mother and my father told me we were second-class citizens. They said, don’t make a lot of noise,” he said.

One day before he would have graduated from high school, the Kimura family was sent to one of the many concentration camps for Japanese Americans. He said he was not bitter.

“I tell my son, who is 22 years old now, that any time you come up against something that is a very bad experience for you, you have to muster up enough courage and foresight to remember that there’s something good that comes out of everything you run into,” he said.

After leaving the camp, the family found that all their property was gone. They wandered around Seattle, turned away from hotels and boarding houses.

Taky Kimura at the graves of Bruce Lee and Lee’s son, Brandon

“My dad’s brother tramped the city for weeks, finally there was an old German guy that had a couple of rooms. My uncle sat on the doorstep every day for two weeks,” said Kimura’s son, Andy.

The landlord said people would “hate him” if he rented rooms to Japanese Americans.

“But my uncle promised we’d keep it clean and wouldn’t cause any problems,” said Andy Kimura.

The family was eventually able to purchase a small grocery store from an older Greek woman, to start again.

But Taky Kimura, at 38, described himself as a “beaten man.”

He described going into restaurants or barbershops and being ignored for hours until he got up the courage to walk out. He couldn’t get a job.

And he saw friends who fared much worse.

Kimura started studying judo, to help with his confidence, and through a friend met Bruce Lee.

Lifting another up

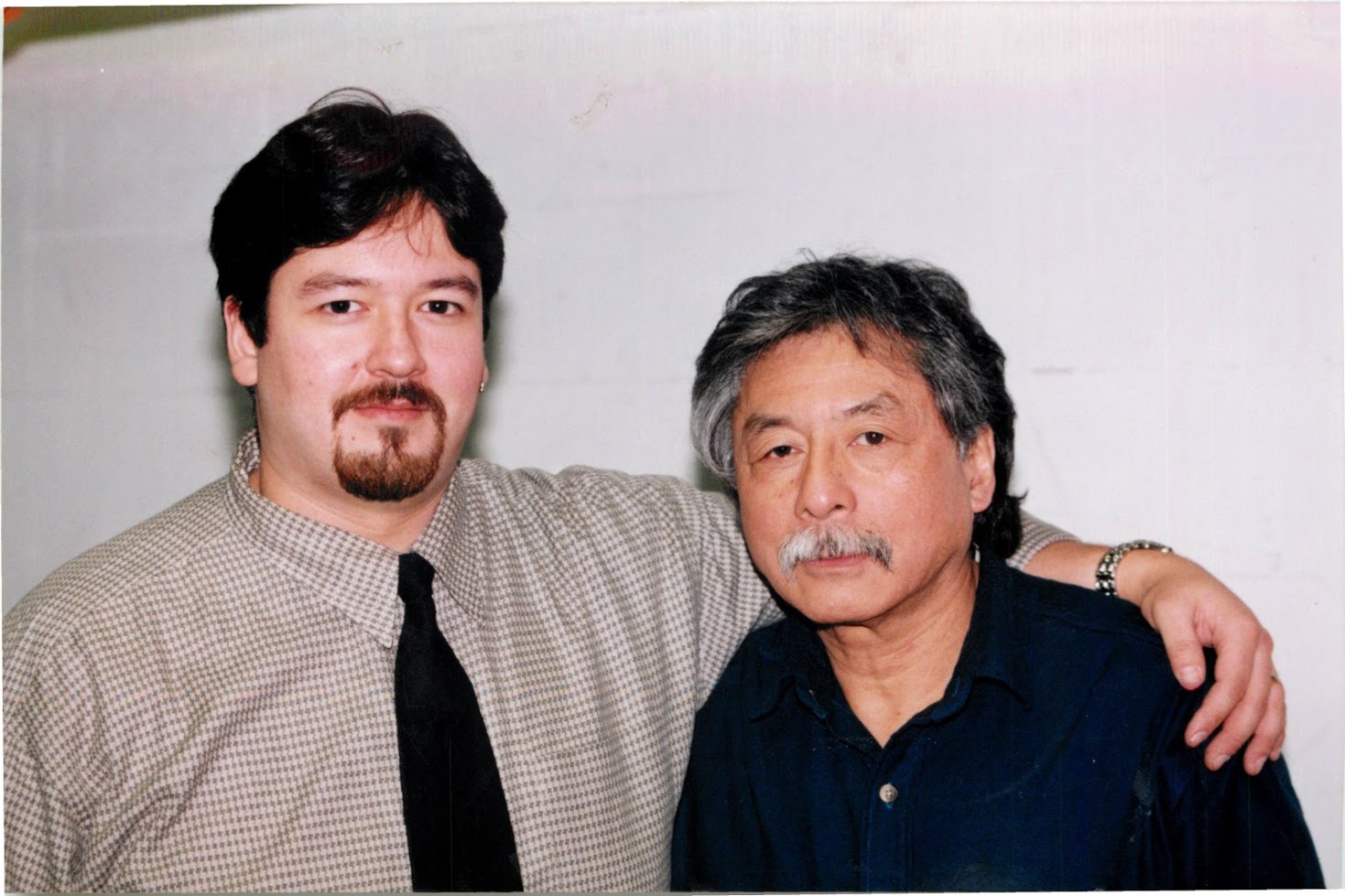

Andy Kimura and Taky Kimura

Kimura was much older than the other students Lee was teaching. But he played a pivotal role: he listened, he encouraged, and he was vulnerable.

Letters written by Lee throughout his life, as collected in the book, “Letters of the Dragon,” show that he opened up about his dreams, his glories in Hollywood, and his disappointments, to only one person.

“It was to Taky Kimura that Bruce Lee opened himself up more as a human being,” wrote David Tadman, author of another book of Lee’s letters, “Regards from the Dragon,” in an email. “He taught me how to listen.”

Kimura had a knack for supporting Lee, both emotionally and financially. Describing one instance in which Lee hit him in the face by mistake in front of the whole class, Kimura explained that he accepted blame for it.

“The doctor admonished me and said, ‘You should be wearing a mask for such a dangerous thing,’” he said.

“And Bruce said, ‘You moved,’ and I didn’t think I moved and I wasn’t going to tell him I didn’t move so I said,

‘Well, I guess I did.’”

Lee had hit him in his glasses, shattering them.

At the same time, Kimura kept the school that he had encouraged Lee to start, going when Lee went to California to break into the movie business.

“Some of my friends, they thought I was crazy doing all this work and not keeping a penny for myself, but I just felt that here’s a man who came along and helped me to revive confidence in myself and make me feel I’m as good as anyone else, that I’m able to reach the potential I’m capable of, so I felt that I owed him something and Bruce did a lot of things for a lot of people,” said Kimura.

But in the end, it was not clear who had done more for whom, who was the one who had actually lifted the other up.

Resistance and acceptance

Kimura’s son saw this spirit of self-sacrifice growing up and he resented it.

His dad had always been there for him, he said. He would have night terrors when he was young, “like a waking dream.” His father, after a long day at the grocery store and then teaching classes at night, would carry him up the hills to the hospital in the middle of the night.

But Kimura’s devotion to his mission, which often meant helping strangers, was galling to Andy Kimura—it made him rebel against the whole world of martial arts.

“There was a time when I didn’t want to have anything to do with it, because it took my dad away from me,” he said.

“He forgot me at school so many times.”

For anyone else, however, Kimura was a godsend.

“No matter how busy he was, he always made the time for anyone who needed his attention and guidance,” said Tadman.

Things changed for Andy Kimura when he was 15 years old. He got into a fight at Nathan Hale High School.

It was part of a major race riot that had been set off by several students telling lies. In trying to defend his friends, he suddenly faced a mob of students.

Growing up around his father, and in his father’s studio, he had always thought of the techniques as “play.”

But suddenly they became serious.

He waded through the crowd, repelling attackers. He became the center of a circle of students pummeling him. He fought back, throwing off dozens. But he ended up in a ditch after being hit in the temple with a brick. The next day, he stayed out of school, and a friend told him that about 30 students showed up with guns to kill him.

However, the reaction that had the greatest impact came from his father.

“I told him when I came home what had happened. His first question was, ‘Are you okay?’ Then he asked, ‘Did you win?’”

He would eventually go on to become his father’s top pupil and finally take over the Jun Fan Gung Fu Institute, founded by Bruce Lee.

A legacy

Kimura was a father figure to many.

Matt Emery, who met him relatively late in his career, teared up when talking about Kimura.

Emery, who now runs his own martial arts studio in Los Angeles, teaches hundreds of children. He explains to them that each move, each punch, each style of combat, is a tribute to a teacher from the past, particularly Kimura.

As he demonstrated a series of whipping punches over a Zoom class to a dozen small children recently, he stressed that these were taught by Kimura and embodied his particular character and mission.

“It is very important in life to have a mentor,” he said. “Sigung Taky Kimura will hold your hand with both of his hands, look you in the eye, and communicate with you as if you have been friends forever,” he said using a title of veneration.

Sue Kay, 75, a former student, said she remembered his “solid, muscular, and strong forearms” as he sparred with her personally.

“He taught me self defense before there were self defense classes for women!” she said in an email.

Bill Seng, a former student from Germany, talked about Kimura and his son taking the time to watch the Bruce Lee movie, “Enter the Dragon,” with him at his home.

Kimura, he said, “created an atmosphere of family and friendship and genuine humbleness,” he said.

Kimura always promoted Bruce Lee. But it was sometimes with a wry, sardonic humor that perhaps explains why Lee liked him so much.

During one exhibition in California, Lee arranged for Kimura to join him as a sparring partner. A video shows Lee wearing a black blindfold and knocking down Kimura several times, whether by design or accident.

But Kimura was always appreciative.

“I’d get a free ticket,” he said. “So I’d get to go down to California for free—and get beaten up in the process.”

Mahlon can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.