By Mahlon Meyer

Northwest Asian Weekly

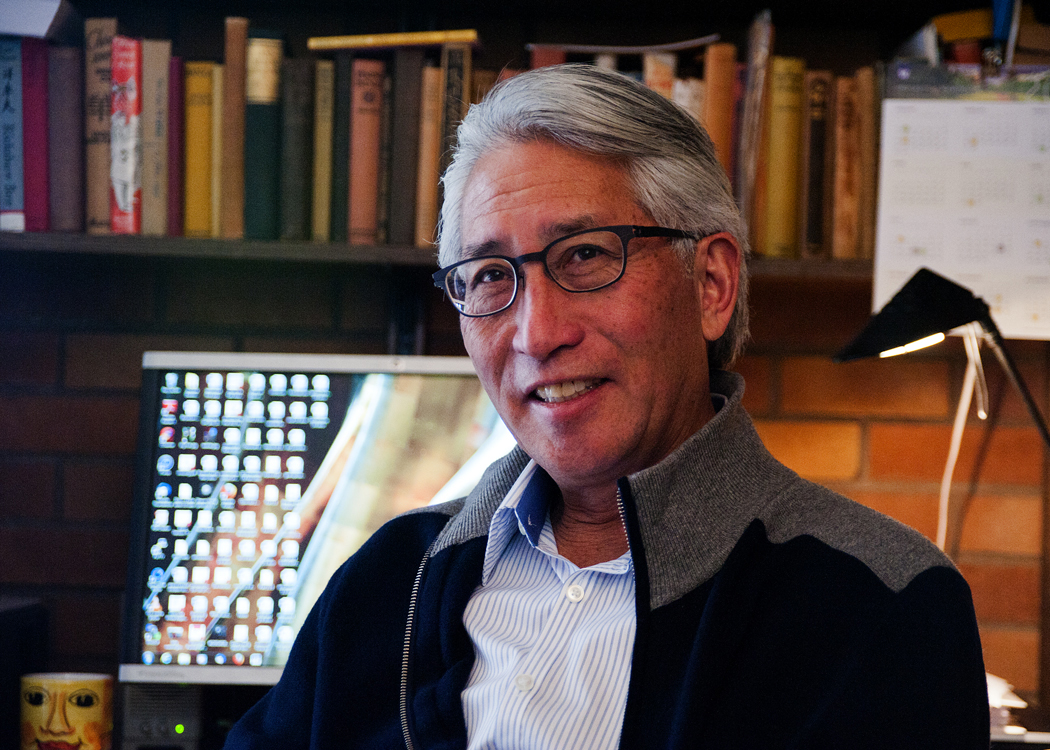

Shawn Wong (Photo from shawnwongwrites.com)

University of Washington (UW) professor and novelist Shawn Wong last week said his battle with Penguin Random House over the copyright of “No-No Boy,” the first Japanese American novel, was coming to a positive close, although he could not provide details.

The victory was part of Wong’s life-long mission as a writer and educator to rescue Asian American voices from oblivion.

“It just got sorted out,” Wong said in an interview with Northwest Asian Weekly. “We’re just waiting for the other shoe to drop.”

“We’re waiting for the good news,” he added.

“No-No Boy” was written by Japanese American author John Okada in the late 1950s about a Japanese American man who refuses to serve in the American army during World War II and, despite his convictions, watches his family, friends, and cultural world implode after the war ends.

“No-No Boy” was written by Japanese American author John Okada in the late 1950s about a Japanese American man who refuses to serve in the American army during World War II and, despite his convictions, watches his family, friends, and cultural world implode after the war ends.

The novel ends after the protagonist’s best friend dies of a war injury, his mother commits suicide, another friend is killed in a bar fight, and he compounds his despair by turning down several job offers believing he can never set right his “mistake.”

Okada died of a heart attack in 1971, after failing to get the novel published in the United States (it was printed in Japan with 1,500 copies).

Wong, an upcoming Chinese American writer at the time, discovered the novel with several writer friends and joined resources to get it published soon after.

Later, he transferred the rights to UW Press.

But in May, Penguin issued its own version, claiming that the copyright was in the public domain.

Wong went on a campaign to save it, not realizing how far it would go.

He first posted a message on Facebook calling Penguin’s action a “moral outrage.”

A colleague forwarded his post to a New York Times writer he knew.

“The New York Times story was big trouble for Penguin,” said Wong.

According to Wong, Penguin had apparently hoped to use the Penguin Classics version of the best-selling book in university classrooms, undermining the UW Press—and the Okada family, which receives royalties.

Penguin, in turn, issued a statement saying it had hoped to “continue important conversations around ‘No-No Boy’ through its inclusion in the Penguin Classics series.”

Half a dozen major media outlets followed with articles and interviews of Wong, who shared his original copyright of the novel on his Facebook page.

The media attention culminated in a statement on June 25 by the American Studies Association (ASA).

“In recent weeks, Penguin Classics’ decision to publish an edition of John Okada’s 1957 novel No-No Boy has been sharply criticized,” said the statement. “In our view, that criticism is warranted. It appears that Penguin Classics proceeded without consultation of the Okada estate or commitments to the distribution of royalties to it.”

Wong was not authorized to go into details, but said the UW Press’ lawyer had just concluded negotiations with Penguin and reached a positive outcome.

As of press time, both UW Press and Penguin Random House had not responded to inquiries.

Wong’s fight against Penguin was part of his life’s mission: to rescue the identities and rights of Asian American voices threatened by mainstream forces.

In his breakout novel, “Homebase,” published in 1979, Wong chronicled multiple generations of his family, each displaced in different ways, starting with his grandfather who endured cruelty and hardship while working on the transcontinental railroad.

In the novel, he creates imagined lives for his forebears, using historical research, poetic prose, and an almost incandescent trance—like conjuring of experiences he seems to channel from long-dead ghosts. This includes creating imagined lives for his parents, who died when he was young.

“I’m always trying to define absence,” he said. “My own absence from other people’s lives, people’s absence from my life.”

Championing “No-No Boy” was another act of rescuing an absent voice—that to some extent is still absent.

The title of the novel refers to Japanese Americans who checked “No” to two questions on a form they were given after being interned. The first asked if they would serve in the U.S. military. The second asked if they would renounce allegiance to Japan.

Those that checked “No” were sent to prison, like the main character in the novel, who checked “No” to both questions, thus earning the disparaging title, “No-No Boy.”

In the novel, the main character, Ichiro Yamada, upon emerging from prison and returning to Seattle, is tormented and attacked by Japanese American veterans for his refusal to join up.

Until this day, according to Wong, many Japanese American veterans still find that an unpardonable sin.

“My own father-in-law was Nisei,” he said, referring to the second-generation of Japanese American immigrants. “He never forgave those that refused.”

But the controversy over “No-No Boy” has drawn attention to other histories of displacement.

“We are reminded of the histories of removal, confinement, and dispossession of indigenous peoples; we are reminded of the differential citizenship assigned to Black people; we are reminded of the camps proliferating on the U.S. nation’s southwestern border; we are reminded of the separation of family members from each other; we are, in short, reminded of the violence that has always and continues to proceed in the name of national security,” said the ASA statement.

Going forward, Wong is finishing another novel that involves an “ivory tower” scholar of dead languages seeking to rescue himself from isolation by becoming a businessman in women’s fashion.

Unlike his recent, real-life victory, however, the protagonist of the novel ends up in failure.

“He learns that he is more alone than ever,” he said.

Mahlon can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.