By Mahlon Meyer

Northwest Asian Weekly

Stanley H. Barer (Photo by Assunta Ng)

Under the speckled shadows outside a coffee shop, Stanley H. Barer held up a finger to make a point. Such quiet force seemed to repose in that finger, that the very air seemed to hold its breath.

It was the same finger, after all, that 40 years earlier had pointed out a new interpretation of U.S. law, which in turn had helped remake the modern world by reopening U.S.-China shipping after 30 years.

His new opinion of U.S. law went into effect in 1979.

Before that, any Chinese ship could be seized by the U.S. government, or by any corporation or individual to regain assets lost when the Chinese Communists came to power in 1949 and froze $200 million in U.S. property in their country.

No Chinese ship had dared to sail openly to America since then.

But at the time, the United States was seeking to bring its law in accord with international law. International law stated that so long as the ship was used only for commercial purposes, it could not be “attached.”

So Barer, a young and handsome lawyer with a perpetual swarthy grin on his face, waited for the law to pass through Congress.

When the law passed, he wrote up his opinion, applying the law to the United States and China, and shared it with bigwigs in government, including Brock Adams, Secretary of Transportation. Adams then shared it with the attorney general, the State Department, and the White House. And they all agreed it would work.

“It was a 180-degree turnabout in American policy,” said Barer, during an interview a few days after the 40th anniversary of the arrival of the first Chinese ship.

Liu Lin Hai, the first Chinese ship to arrive at the Port of Seattle on April 18, 1979. (Photo provided by Port of Seattle)

Shortly thereafter, that first Chinese ship did arrive — the Liu Lin Hai — with a beaming, broad-faced captain leading dozens of Chinese sailors down a ramp and into the Port of Seattle.

Although the Chinese later expanded their voyages to California, eventually preferring Oakland while continuing to use Seattle for trade, the first voyage was significant because it showed that trade between the two countries that had been technically not speaking to each other for 30 years could commence.

Captain and crew of the Liu Lin Hai (Photo provided by Port of Seattle)

“That first ship was symbolic of the possibility of trade as a major anchor of U.S.-China relations,” said David Bachman, Henry M. Jackson Professor of International Studies at the University of Washington (UW).

But there is still no clear consensus about the value of the trade.

Added Bachman, “Trade has increased prosperity for both countries, but the benefits of that trade have been unevenly distributed. Arguably, many in the state of Washington have benefited from that trade. But Chinese competition, in some cases with unfair advantages, has harmed firms and individuals as well.”

Challenging authority

In helping to open up U.S.-China trade, Barer was drawing upon a childhood in which he had learned to challenge authority.

As a young man of Jewish ancestry in rural Walla Walla, Barer had, in fact, learned of the necessity of doing so. Despite high grades, he was passed over for the National Honor Society and later learned it was because he was Jewish.

That experience and other similar experiences propelled him into a practice of standing up for himself — and others.

His first experience came when he was driving a vehicle with loud exhaust pipes that were “rumbling,” he said. He was eventually arrested.

“I went before the judge and he said, ‘You’ve been stopped several times,’ and he said, ‘You’re going to end up on the wrong side of the Walla Walla State Penitentiary.’ I said, ‘No, you’re wrong judge, I’m going to go to university and end up a judge like you.’”

His mother, who was in the courtroom that day, lowered her face into her hands. His father was furious.

Years later, however, Barer came back to his hometown and was visiting the law library. The same judge, apprised of this, asked to see him.

Barer immediately apologized to the judge for his impertinence.

But the judge had seen his picture in the paper with Senator Warren G. Magnuson and he said, “You don’t have to apologize — you were right!”

Helping to remake the world

When shipping commenced in 1979, both the United States and China were excited to take part in it, on a voluntary and reciprocal basis.

That did not mean, however, that both sides had reasonable expectations.

The U.S. side, as it had done throughout modern history, saw China as a bonanza for marketing new products.

The Chinese, on the other hand, had little understanding of the U.S market. Their first shipment of goods, according to media reports at the time, included pigs’ feet, sausages, and canned jellyfish.

Much has changed in 40 years. Today, the United States is China’s largest trading partner. In 2018, the United States exported $120.3 billion worth of goods to China and imported $539.5 billion worth of products, according to the Office of the United States Trade Representative.

Last year, Washington state maintained a somewhat more equal ratio, importing $16 billion worth of goods and exporting roughly the same amount to China, according to the United States Census Bureau.

While trade with China has come under fire in recent years, some economists argue that healthy trade prevents war.

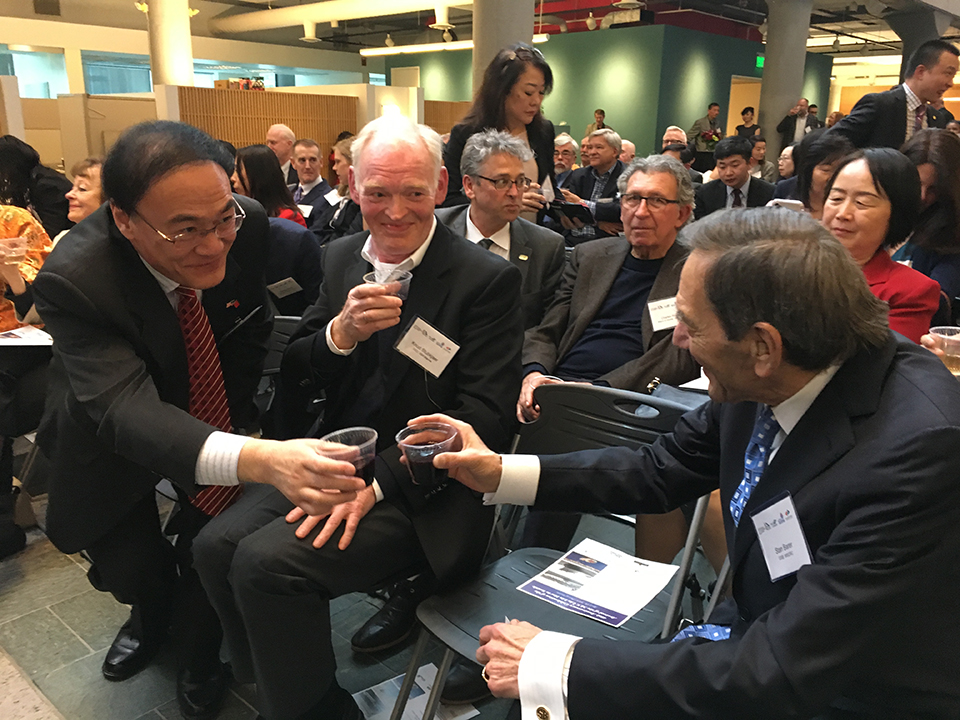

Chinese Consul General Wang Donghua toasted Stan Barer (right) at the Port of Seattle celebration of the 40th anniversary of the first Chinese ship coming to Seattle. Barer was honored at this event. (Photo by Assunta Ng)

Matthew O. Jackson, a Stanford University economist, in his new book, “The Human Network,” argues that trade is “vital” in preventing conflict.

“It is obvious from the data that countries that have substantial trading relationships with each other simply don’t go to war with each other, regardless of their politics,” said Jackson, in an email. “The costs of such conflict become too high. Essentially, all of the remaining major conflicts in the world are between countries that have relatively low amounts of trade with each other.”

Still, decreasing trade with China would not necessarily bring about an increasing chance of war.

That would happen for other reasons, according to Bachman, the UW professor.

“When that first ship came to Seattle, there was little prospect for direct war between China and the U.S.,” he said. “Arguably, the chances of war have increased in recent years, but that is for reasons related to geopolitica and Taiwan.”

Mahlon can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.