By TAD VEZNER

St. Paul Pioneer Press

ST. PAUL, Minn. (AP) — It’s 17 minutes till the battle at the butterfly house.

Car after car rolls up at the Minnesota State Fairgrounds on a chilly weekend. No events are scheduled. Nothing is going on that anybody can see, the St. Paul Pioneer Press reported.

“Five minutes,’’ says Chris Debban, 36, of Roseville.

“I gotta warm up before it starts,’’ replies his mother, Tammie Debban, 55, after a quick cigarette. The area around the butterfly house is getting packed, with barely anywhere to park for two blocks. “Should I change my — ”

“No, I’m sticking with these,’’ her son replies, gesturing at his phone.

Everyone’s looking at their phones. People get out of cars, come stand by the butterfly house and look at their phones some more. A few look up to introduce themselves.

“Two minutes,’’ Chris Debban says.

And then it’s time: The dozens of strangers begin furiously punching their screens, in unison.

Across the country, servers have separated the crowd into 20-person teams, each fighting a giant monster with virtual Pokemon. There’s no way they could beat that beast on their own.

Over the past year, the “Pokemon Go’’ craze has dipped, shifted and amped up again. With a major, notable twist: What seemed like a craze for kids, teens and parents has shifted to mostly just parents. Or, simply, adults.

Of the more than 100 random people who assembled to fight a virtual monster on the Fairgrounds recently, two were children. The vast majority stretched from their 20s to their 60s.

And with a new feature—“raiding’’—they’re practically required to gather in large groups.

“Man, it’s addicting. I stopped playing other stuff and started playing this, because there’s people. I’ve never seen so many people actually get out to actually interact,’’ Chris Debban said.

“Sometimes I’ll stop by (the Fairgrounds) on my way home because it’s on my way,’’ said Nell Wirth, 35, Roseville. “I just want to unwind.’’

Over the past year, the game has encouraged group play, in a not-so-subtle way. There are some fights players can’t possibly win on their own—they need others in close physical, not virtual, proximity. On top of that, fights are coded to be easier with friends, or at least with other people, standing a few meters away.

“The real mechanic isn’t really the battle. It’s people grouping together in the real world. And that requires work,’’ said Matt Slemon, product manager for San Francisco-based Niantic Inc., the creator of “Pokemon Go.’’

Slemon goes on to describe Niantic’s governing philosophy—one it’s banking on to make its games stand apart, even as it encourages its users not to.

“As digital worlds become more interesting, that shouldn’t make the real world less interesting,’’ he said.

Some city officials have taken notice in recent months—with “raid’’ groups crowding parks and municipal parking lots, often at odd hours.

“We got calls everywhere (about ‘Pokemon Go’), with parks. Officers would pop in and talk to people,’’ said Roseville police Lt. Erika Scheider. “That just became a normal thing.’’

“Once you know what it is, you start noticing it everywhere,’’ said St. Paul City Council President Amy Brendmoen.

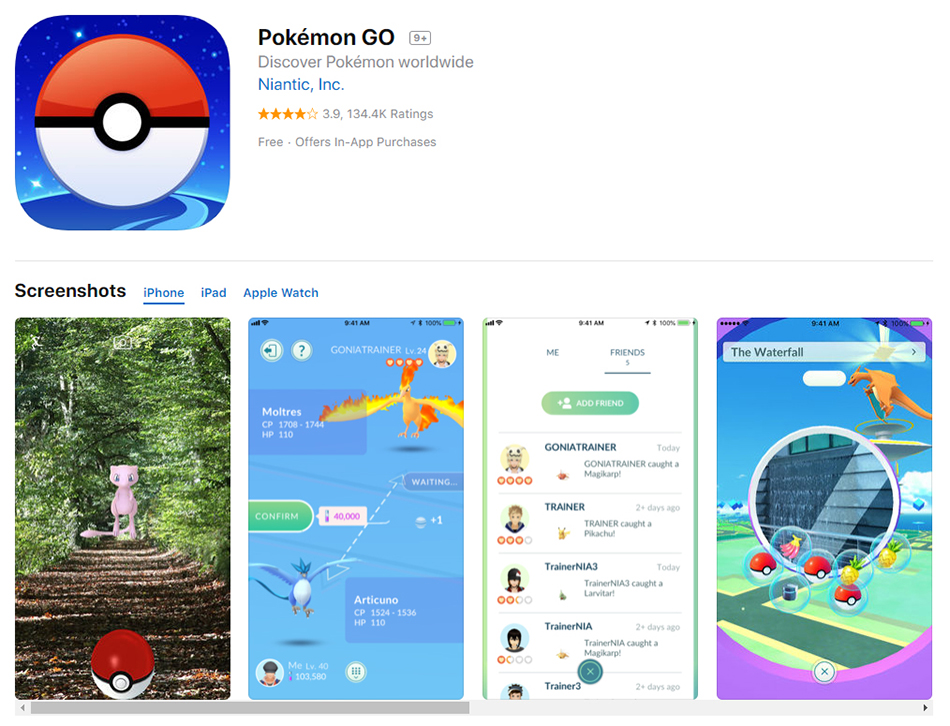

When “Pokemon Go’’ was introduced as a smartphone app a couple of years ago, it became an instant phenomenon. Also, the prime demographic appeared to trend younger.

But the game’s creators pointed out the older users were always there. The initial release in 2016 was timed to coincide with the 20-year anniversary of “Pokemon’’—short for “pocket monsters’’—which was first released for the Nintendo Game Boy in 1996 and quickly became a popular anime series.

The same people who were fans then are fans now, the creators believe.

Still, “Over time as kids’ attention kind of wanders off, the grandparents and parents (they were playing with) might find that they were actually enjoying the game,’’ Slemon said. “At this time, rather than kids getting their grandparents to play, it’s adults getting each other to play.’’

The latest iteration really started in 2014, when a couple of developers at Google Maps programmed an April Fools’ Day prank—allowing people to see and easily catch Pokemon monsters while using the service.

The success of the single-day event planted the seed for the eventual creation of the game.

But developers see “Pokemon Go’’ as different from other apps in a big way: what they call the “getting-off-the-couch effect.’’

By dropping virtual “eggs’’—hatchable monsters that players can see only on their phone, with a timer showing when they will hatch and start fighting—in common gathering places, the game’s creators got strangers in the same place. From there, game mechanics encourage them to actually talk to each other.

“They are set up to reward people for having friendships,’’ Slemon said.

For instance, there are gifts in the world that players can’t open themselves—their only purpose is to be given to somebody else.

And there’s an in-game currency called Stardust. It can’t be bought with money, only earned through actions in the game. One of its purposes is to allow players to trade monsters with each other.

“Stardust cost is dramatically reduced if you’re trading with a higher-level friend,’’ Slemon said.

Level? There are “basic’’ friends, who’ve just met, and “best’’ friends, who’ve known each other for at least three months and regularly play together.

The model appears to have paid off. The company says it’s seen a 35 percent increase in active usage since May.

“It is a lot more older people (now),’’ Chris Debban said. “I find it crazy. Como Park’s crazy, too. Rice Park — oh my God. I can’t get in.’’ In the south metro, the Mall of America is big, noted frequent player Wirth.

“In summer, people bring music and hand out food. It can get kicking,’’ Debban said, looking around at the dozens of people standing around him on the chilly day, a few of whom approached and talked to him.

“Even more than this.’’