By LAURIE KELLMAN

Associated Press

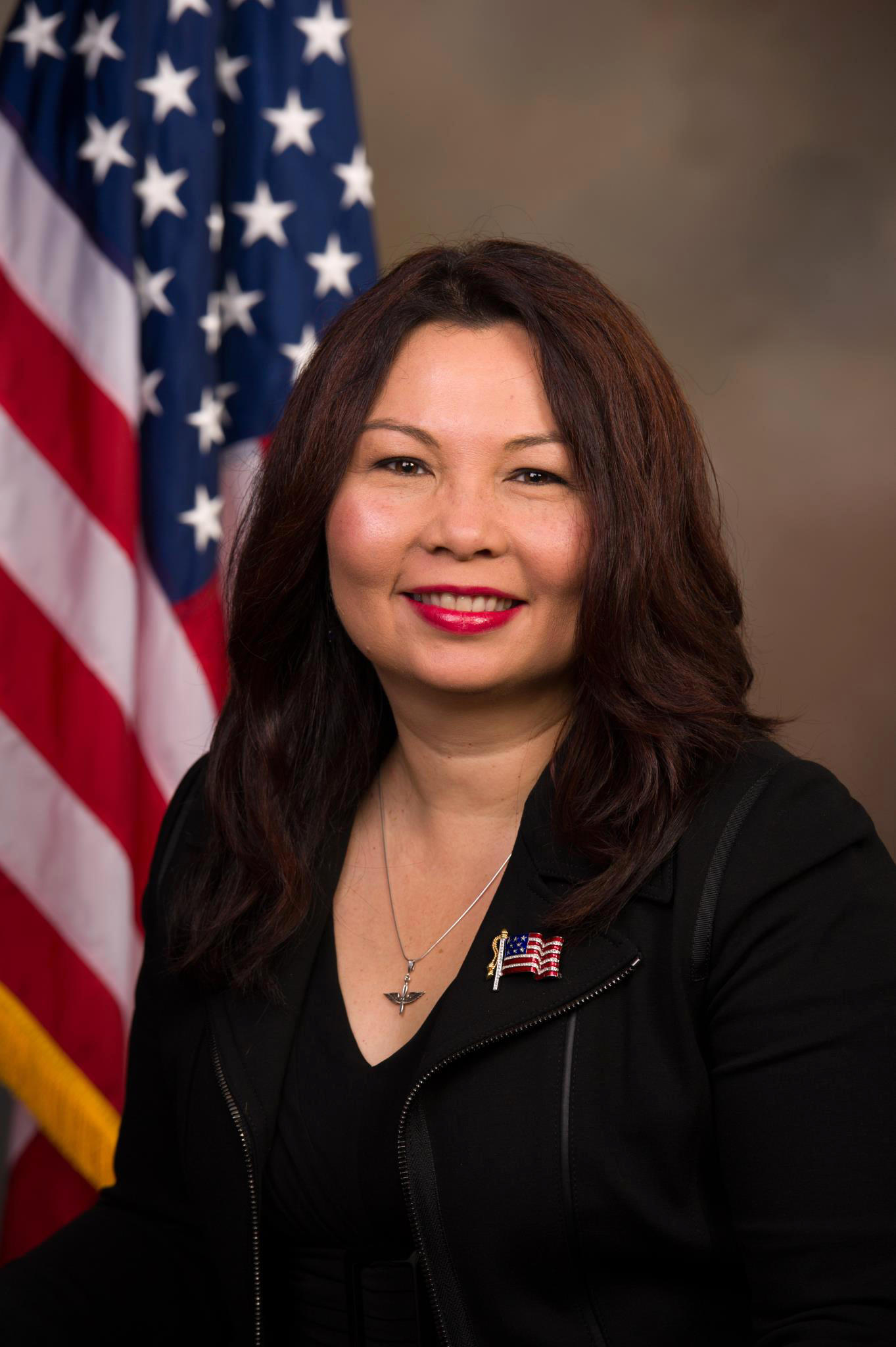

Sen. Tammy Duckworth

WASHINGTON (AP) — Breaking down barriers is nothing new for Sen. Tammy Duckworth, and that’s the way she likes it.

The decorated Iraq War veteran who lost both legs when her helicopter was shot down is an Asian-American woman in the mostly white, mostly male and very fusty Senate. And now, with a baby due in April, she’ll be the first senator to give birth while in office.

And so, along with her legislative and political goals, the Illinois Democrat is adding a new one: educating the tradition-bound Senate on creating a workplace that makes room for new moms.

“She’s been through things that you and I will probably never understand. So I’m sure for her (having a baby) is in no way daunting,” said Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler, R-Wash., who had two children while serving in Congress. “She’s also someone who’s had a whole career in a male-dominated world.”

Duckworth, who turns 50 in March, says she appreciates the historic nature of her baby’s birth, as well as the fact that she represents working mothers and women having babies later in life. She fully expects to have to find a place to nurse in some quiet parlor off the Senate floor.

But she says having a baby, a second daughter, is just one of many stops on the trail ahead.

“This is the last job that I want,” Duckworth said of the Illinois Senate seat once held by Barack Obama.

The former president is one of several men she ticks off as mentors and role models. They include Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., former Sen. Bob Dole, R-Kan., and the late Democratic Sens. Daniel Inouye of Hawaii and Edward Kennedy — all backers of the Americans with Disabilities Act, which made the nation’s landscape a little easier to navigate.

But she’s sees both problems with compliance and efforts to undermine the law.

She points to flaws in Chicago’s mass transit system, for example, and in a ladies’ room at a U.S. embassy overseas. And floating through Congress now is a bill designed to curb frivolous lawsuits under the ADA that Duckworth and others say weakens it.

Duckworth is already in the history books. She’s the first female amputee elected to Congress, the first Asian-American to represent Illinois in Washington and the first member of Congress born in Thailand.

Her story of resilience and grit set her in the rare company of grievously injured veterans who later served in the Senate — Dole, a World War II veteran, and John McCain, who was kept prisoner for more than five years in Vietnam.

“If you take gender out of it, it’s not that new,” said Duckworth, a year into her own Senate term.

But gender can’t be ignored as the nation reckons with sexual misconduct at home and in the workplace, especially since Congress is not exactly known for being on the leading edge of equality. The first area specifically set up for lactation opened in the Capitol only a dozen years ago. The House installed its first lavatory for women lawmakers in 2011. The Senate has had its own women’s restroom for 25 years.

Duckworth, one of 22 women in the Senate, has the experience to give her policy advice and criticisms of President Donald Trump an especially authoritative edge.

His demand for a military parade? “Our troops in danger overseas don’t need a show of bravado, they need steady leadership,” she said.

His complaint that Democrats didn’t sufficiently applaud his State of the Union address?

“I will not be lectured about what our military needs by a five-deferment draft dodger,” reads the Tweet pinned atop her page, referring to Trump’s deferment from Vietnam due to a foot ailment. She refuses to “mindlessly cater to the whims of Cadet Bone Spurs and clap when he demands I clap.”

CBS’ “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” gave Duckworth full credit for the nickname. In a gag ad earlier this month, a new G.I. Joe doll resembling Trump, named “Cadet Bonespurs,” lolls in a hammock while his comrades march off to war.

When Trump tweets that Democrats don’t care about the military, “she takes that personally. She answered personally,” said Durbin.

Politics and the military were not Duckworth’s original goals.

As she worked on a master’s degree in international affairs in the early 1990s at George Washington University, Duckworth was aiming to become an ambassador. She signed up for ROTC to learn more about the military. She fell in love with the challenge — and with a cadet named Bryan Bowlsbey. They married in 1993. Duckworth has said she applied to fly helicopters because she wanted the same power as men — and because it was one of the few combat jobs open to women.

She was the senior officer co-piloting a Black Hawk on Nov. 12, 2004, when a grenade fired by an Iraqi insurgent exploded in a fireball at Duckworth’s feet. She lost both legs and partial use of her arm and faced a grueling recovery.

As she recovered, Duckworth befriended some important members of the Senate. Durbin invited Duckworth to be his guest at President George W. Bush’s 2005 State of the Union address. And Dole, who had lost much of the use of one arm to war, dedicated his 2005 book to her. Duckworth, he wrote, “represents all those with their own battles ahead of them.”

But for all of her powerful patrons, achievements and drive, the Senate terrain can still seem bumpy.

One day in December as Duckworth wheeled around a corner in the Capitol toward the Senate’s historic vote on tax cuts, a young police officer stopped her. The elevators, he said, were reserved “for members only.”

Duckworth looked up and, all business, informed him that she’s the junior senator from Illinois.

The officer let Duckworth through — with apologies.