By Andrew Hamlin

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

I tried to call Ishiro Honda, once. I was about 10, and I loved reading about his Godzilla stories and watching them on KSTW-11’s “Sci-Fi Theater.” (I wanted to stay up late and catch more good ones, like Honda’s classic “King Kong vs. Godzilla,” but my bedtime was nine o’clock.)

I tried to call Ishiro Honda, once. I was about 10, and I loved reading about his Godzilla stories and watching them on KSTW-11’s “Sci-Fi Theater.” (I wanted to stay up late and catch more good ones, like Honda’s classic “King Kong vs. Godzilla,” but my bedtime was nine o’clock.)

I didn’t get very far, partly because I didn’t understand that Information couldn’t give me numbers outside the United States; partly because I was still calling him “Inoshiro Honda,” a mistake that crept into Western versions of his films, used by fans, and even by critics, including the widely-respected Susan Sontag, one of the first American pundits to take Honda’s films seriously.

Being taken seriously was a big problem for Honda, who worked on films and television between 1934 and 1993 (though he gave up directing films in 1975), and counted the legendary Akira Kurosawa amongst his best friends. Honda made a diligent and humble worker bee for, most of the time, Toho Studios. He turned out documentaries, dramas, comedies, coming-of-age stories, and even a yakuza crime picture, 1961’s “A Man in Red.” He worked under Kurosawa after both men had grown old, effectively becoming a second director on such epics as “Kagemusha” and “Ran.”

Still, all anybody remembers is the giant rubber monsters, Godzilla leading the pack.

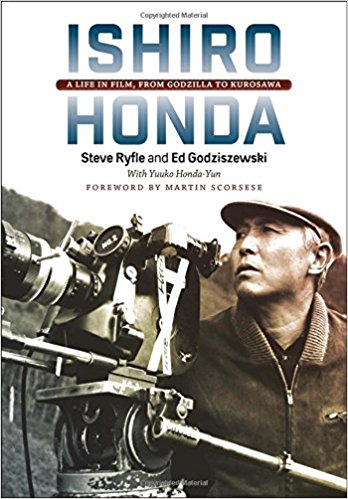

The new book “Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa,” by Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski with Yuuko Honda-Yun (the director’s granddaughter), compiles a life, a life’s work, and even throws in relevant Japanese history, relating to Honda’s original film visions. Honda did not make personal films, or autobiographical films, as we generally understand those terms. He did not shoot political films or social justice polemics. But even with the rubber monsters thrown in, he could comment astutely on Japanese society, and even insert personal concerns.

It didn’t seem like a life meant for film, at first. Honda’s father and grandfather were Buddhist monks, in a tiny town that’s since absorbed into a larger hamlet. He loved science and would always love science, but scientific school studies flummoxed him. He couldn’t seem to master equations. He was drafted into the Japanese army three times, and he avoided seemingly-certain death at least twice. His marriage to Kimi Yamasaki was not an arranged marriage, and her father retaliated by cutting both of them off. (Over the years, pressure to conform to an arranged marriage would turn up again and again in Honda’s plots.)

Kurosawa, a year older than Honda and far more blustering, got into the director’s chair first. But that wasn’t at all fair. Honda ended World War II as a prisoner of war in China, while Kurosawa skipped service thanks to, ironically, family military connections. Honda’s early films mixed documentary approaches, getting up close on rituals and processes, with fictional characters and stories. That stood him well when the time came to tell stories of huge monsters, usually radioactive, stomping Tokyo and everything else they could find to stomp. The very idea was ludicrous, always. But the director didn’t go for lurid, or, at first, for lampooning. He rendered terrors viable.

And yes, Godzilla (originally “Gojira,” a smushing together of the English “gorilla” and the Japanese “kujira,” which means “whale”) was meant to comment on the radioactive age, although Honda, at first, did not point fingers right at the United States for its use of the atomic bomb against Japan. Time after time, in monster films, science fiction films, and films “limited” to the everyday Earthbound, Honda quietly asked questions.

In 1969’s “All Monsters Attack,” aka “Godzilla’s Revenge,” he gave us a small, lonely, bullied little boy who travels to Monster Island and meets Godzilla, through flights of hallucinogenic fancy. That’s contrasted with the ugly industrial blight just outside the boy’s door.

Honda says in effect, we pushed ourselves into heavy industry, and galvanizing the economy. And it’s working. But we pay a price for doing it this way. Pollution threatens physical, mental, and spiritual health, even as it corrodes the natural beauty Japan supposedly prides itself on. And all of these latch-key children, coming home to empty houses, both parents working. No supervision, and no encouragement. What effects will this have? What will become of them when they grow up?

Honda’s films were often chopped, panned, scanned, badly dubbed, and/or badly narrated, in America. His original visions meant nothing to U.S. distributors, who often left in all the monster fights, masterminded often by the magnificent Eiji Tsuburaya, and made mincemeat of what Honda was trying to say underneath. Honda put up with this. His films, even the American reworkings, played matinees, drive-ins, and American television slots morning, afternoon, and night.

He never plotted for a spot in history, but he ended up introducing Japanese cinema to the West, far further than his friend, the more widely-praised Kurosawa. The Kurosawa dramas and epics boasted higher production values and far better reputations with critics. But you couldn’t sit down to one of them on late-morning Saturday TV, with a big bowl of heavily-sugared cereal.

In the end, Honda was probably too modest and self-effacing for his own good. He let studios tell him what to do. After he accidentally invented the “kaiju” (monster) genre in Japan, the studio heads kept him busy filming those at the expense of anything else. And when he found he could no longer keep doing more work on ever-smaller budgets, he got out of the pool.

The Hondas had to sell their huge house, where they’d held huge parties for their famous friends. But they settled into a smaller house in a Tokyo district called Seijo. Honda, between TV work and Kurosawa work, lived there until his death in 1993. According to the book, “He continued to welcome admirers arriving at his door, or he’d accept their phone calls, even the occasional collect call from overseas.”

If I’d only dialed two more numbers—Japan information, and then a Seijo number—I might have heard his voice.

Andrew can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.