By The Associated Press

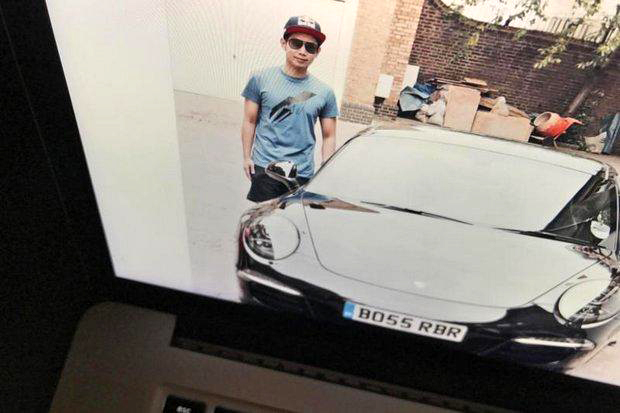

This Instagram photo dated July 2, 2015, shows Vorayudh in London with a black Porsche and customized license plate. (Social media photo via AP)

BANGKOK (AP) — The Ferrari driver who allegedly slammed into a motorcycle cop, dragged him along the road and then sped away from the mangled body took just hours to find, as investigators followed a drip, drip, drip trail of brake fluid up a street, down an alley, and into the gated estate of one of Thailand’s richest families.

The prosecution of Red Bull heir Vorayuth “Boss” Yoovidhya, however, has been delayed for close to five years. The times when Vorayuth has been called in on charges, he hasn’t shown up, claiming through his attorney that he was sick or out of the country on business. And while statutes of limitations run out on key charges this year, it’s been widely assumed that he’s hiding, possibly abroad, or living a quiet local life, only going out in disguise.

He isn’t.

Within weeks of the accident, The Associated Press has found, Vorayuth, then 27, was back to enjoying his family’s jet-set life, largely associated with the Red Bull brand, an energy drink company co-founded by his grandfather. He flies around the world on private Red Bull jets, cheers their Formula One racing team from Red Bull’s VIP seats and keeps a black Porsche Carrera in London with custom license plates: B055 RBR. Boss Red Bull Racing.

Vorayudh and his mother Daranee attended last year’s Formula 1 Grand Prix in Abu Dhabi.

Nor is he all that hard to find. Just last month, social media clues led AP reporters to Vorayuth and his family vacationing in the ancient, sacred city of Luang Prabang, Laos. The group stayed at a $1,000-a-night resort, dined in the finest restaurant, visited temples, and lounged by the pool before flying home to Bangkok.

Critics say the inertia in the Red Bull heir’s case is just another example of longstanding privilege for the wealthy class in Thailand, a politically tumultuous country that has struggled with rule of law for decades. The military general who came to power in a 2014 coup declared war on corruption, pledging to make Thailand an equal and fair society. But car accidents are frequently cited as an example that injustice persists, with “Bangkok’s deadly rich kids,” as one Thai newspaper described it, often receiving far more lenient sentences than ordinary Thais.

The Yoovidhya family attorney did not respond to AP’s request to interview Vorayuth.

British historian Chris Baker, who with his Thai wife, Pasuk Phongpaichit, has written extensively about inequality, wealth and power in Thailand, said he wasn’t surprised Vorayuth hasn’t been prosecuted.

“There is most certainly a culture of impunity here that big people, which means roughly people with power and money, expect to be able to get away with a certain amount of wrongdoing,” said Baker. “This happens so often, so constantly, it is very clearly part of the working culture.”

Meanwhile, Vorayuth has been summoned again. He was due at the prosecutors’ office on March 30.

Vorayuth and his siblings came of age in a private, extended family whose fortune expanded from millions to billions as they grew up. His brother is nicknamed Porsche, his sister Champagne.

Vorayuth received a British education at Bradfield College, a pastoral brick-and-stone boarding school in the Berkshire countryside. Boys wear suits and ties, and it costs $40,000 a year. Some of Thailand’s wealthiest families send children there.

Back in rural Thailand, police Sgt. Maj. Wichean Glanprasert didn’t have many opportunities, but he was ambitious and determined. The youngest of five, he was the first in the family to leave their coconut and palm farm for the city, the first to get a government job, to graduate from college. He paid for his parents’ care as they died, and supported a sister through cancer. He had no children, but planned to put his brother’s kids through college, and teased a favorite nephew he’d have to care for him in old age.

Their lives literally collided just before dawn on Sept. 3, 2012, when Vorayuth’s Ferrari roared down Sukhumvit Road, one of Bangkok’s main drags. The bloody accident scene made national headlines for days.

The dead policeman’s brother, Pornanan Glanprasert, didn’t so much hear the news as feel it. His beloved younger sibling Wichean was dead, said the caller. His crushed body was in the street.

Over the next few hours, police traced their way to the Red Bull compound. Initially investigators said a chauffeur had been behind the wheel of the car, windshield now shattered, bumper dangling. But after senior officers arrived, Vorayuth turned himself in, his cap pulled low, his father holding his arm. Later that day, the Yoovidhyas put up $15,000 bail at the police station and went home.

For Pornanan and his sisters, here was tragedy beyond belief. In the days after the death, they attended funeral rites at the temple, where Buddhist monks chanted and incense burned.

One day Vorayuth and his mother made a surprise, private visit. Dressed in black, they pressed their palms together and bowed to Sgt. Maj. Wichean’s portrait.

The policeman’s family painfully grieved, but they figured at least there would be justice. Wichean was a police officer. Certainly the criminal justice system would hold his killer responsible.

“At first I thought they’d follow a legal process,” said Pornanan.

Now he’s not so sure.

Over days and months, the case unfolded. The Yoovidhya family attorney said Vorayuth left the scene not to flee, but because he was going home to tell his father. As for blood tests showing Vorayuth was well over the legal alcohol limit, his attorney said his client was rattled by the crash and so drank “to relieve his tenseness.”

Facing a flurry of public skepticism about whether affluence and influence would let Vorayuth off the hook, Bangkok’s Police Commissioner Comronwit Toopgrajank promised integrity.

“We will not let this police officer die without justice. Believe me,” Comronwit said. “The truth will prevail in this case. I can guarantee it.”

But when he retired in 2014, the case was still unresolved. “I am disappointed,” he says now.

Vorayuth’s attorney met with Wichean’s family, who accepted a settlement of about $100,000. In turn, they were required to sign a document promising not to press criminal charges, eliminating Thailand’s legal option for victims to take suspects to court if police and prosecutors don’t take action.

Pornanan says his portion of the settlement sits in the bank. Blood money, he calls it.

Since then, Vorayuth has missed several prosecutor orders to report to court on charges of speeding, hit-and-run, and reckless driving that caused death. Police said Vorayuth admitted he was driving, but not recklessly — the officer swerved in front of him, he said. The speeding charge expired after a year. The more serious charge of deadly hit-and-run, which police say carries a maximum six-month sentence, expires in September. Reckless driving charges expire in another 10 years if they go unchallenged.

Often when people don’t show up for court, police or prosecutors collaborate to ask the court for an arrest warrant. That hasn’t happened.

Complicating matters, Yoovidhya’s attorney has repeatedly filed petitions claiming his client is being treated unfairly in the investigation.

Police spokesman Col. Krissana Pattanacharoen said his agency has done everything in its power to charge Vorayuth, and that they’ve informed his attorneys of yet another date that he must show up at the prosecutor’s office to hear the charges: March 30, 2017.

“I am not saying it is a case where the rich guy will get away with it,” said Krissana. “I can’t answer that question. But what I can answer is, if you look at the timeline here, what we did, by far there is nothing wrong with the inquiry officers who are carrying out the case.”

Prayuth Petchkhun, a spokesman for the prosecutor’s office, said the case is under review because extra investigation was needed. He would not specify what that extra investigation involved.

Thammasat University law professor Pokpong Srisanit said the situation is “not normal” but does appear legal. He noted that with enough bureaucratic maneuvering, some suspects manage to let time run out on charges and have the slate wiped clean.

“There is a problem with Thai law,” he said.

Meanwhile, the Thai media, which has followed the case closely, figured he was laying low.

Last year the Bangkok Post said that after paying the settlement in 2012, Vorayuth “has been out of the country or otherwise unable to answer the criminal case against him in the years since.”

A few weeks after the article appeared, a photo of Vorayuth was posted online. He was on the beach at a seaside resort south of Bangkok.

While Vorayuth’s legal case has been on hold since 2012, his carefree, expensive life has not.

Three months after the accident, Vorayuth was at the Red Bull Singha Race of Champions, staged for the first time in his hometown Bangkok. Smiling in his Red Bull cap at the stadium, surrounded by cousins and friends, a VIP pass dangled from his neck.

More than 120 photos posted on Facebook and Instagram since then, as well as some racing blogs, show Vorayuth visited at least nine countries since Sgt. Maj. Wichean’s death. Stops include the Wizarding World of Harry Potter in Osaka, where he posed wearing robes from Hogwarts School’s darkest dorm, Slytherin House. He’s cruised Monaco’s harbor, snowboarded Japan’s fresh powder, and celebrated his birthday at Restaurant Gordon Ramsay in London. His friends and cousins posting about him have hundreds of thousands of online followers.

Although his own social media accounts are mostly private, he was tagged (at)bossrbr more than 60 times, sometimes responding with emojis or comments. Last summer in Japan he posted a 10-second video of sausage and eggs decorated with seaweed eyes, tagging a young relative. His parents responded with a thumbs-up.

His lifestyle — soaking in an Abu Dhabi pool, dining in Nice, France, holding a $10,000 bicycle in Bangkok — is supported by his family’s billions.

Vorayuth’s grandfather, Chaleo Yoovidhya, grew up in poverty, the son of a duck seller. He was known as a modest, humble man who insisted on privacy. He founded T.C. Pharma in 1956 to import European medicines, but over the decades developed more products, especially drinks sold by the bottle or can.

A few years before Vorayuth was born, Chaleo partnered with an Austrian entrepreneur, Dietrich Mateschitz. They put in $500,000 each to carbonate and globally market T.C. Pharma’s caffeine-powered syrupy energy drink popular in Thailand among laborers, taxi drivers and jet-lagged tourists. In 1987, when Vorayuth turned 1, Red Bull Energy Drink went international and his family’s fortune boomed.

Red Bull sold more than 6 billion of its iconic slim cans in 2016 in more than 170 countries. It has its own media company, a professional soccer team, race cars and jets. The company sponsors concerts, events and athletes worldwide, all ostensibly pumped up with the sweet drink.

Mateschitz owns 49 percent of the company, the Yoovidhya family 49 percent in a complex licensing agreement with T.C. Pharma. Vorayuth’s father Chalerm Yoovidhya, the oldest of 11 siblings, holds the final 2 percent. Red Bull reported more than $6 billion in sales last year. Forbes estimates Chalerm’s net worth at $9.7 billion.

As the family’s wealth has grown, many of the younger generation have become glamorous socialites, traveling the world to shop, dine and play. The family co-owns the only Ferrari dealership in town, as well as a winery. Three generations gathered regularly for birthdays and anniversaries, and the younger family members also dance and drink in Bangkok’s nightclubs.

Vorayuth’s legal situation is far from unique.

Last year, the son of a wealthy Thai businessman slammed his Mercedes Benz at high speed into a smaller car, killing two graduate students. His case is still pending in court. In 2010, a 16-year-old unlicensed daughter of a former military officer crashed her sedan into a van, killing nine people. The teen, from an affluent family, was given a two-year suspended sentence and didn’t complete community service until last year.

Those cases are markedly different than most deadly car crashes, in which Thais are routinely arrested, prosecuted and sentenced to jail.

In a country where intimate ties between money, power and politics have toppled governments and sparked violent attacks, impunity can be a lightning rod. A billionaire prime minister deposed in 2006 was convicted of corruption, but stays out of the country to avoid going to jail. His sister, who came to power in 2011, was thrown out by a military coup backed by other wealthy elites.

Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, a former commander of the Thai Army, says he’s committed to rooting out corruption and crime. But the cases of Vorayuth and other elites have bred skepticism.

“It is no wonder people with money and influence think they can avoid facing the legal consequences for causing carnage on the streets,” said the Bangkok Post in an editorial last year. “History shows they can.”

Today in their small apartment, Pornanan keeps a few photo albums of his brother. In a glass cabinet there’s a larger framed portrait.

At first he was angry. Now he’s just deeply sad. About his brother. And about a criminal justice system he says runs on a “double standard,” one for most people who face their crimes, and one for the elites who don’t have to pay the price.

He tries not to think about where the man he calls “Boss” might be, assuming he’s out of the country: “I think he does not want to tarnish his reputation.”

It remains unclear whether police and prosecutors will do anything.

Last month on Instagram, a friend posted a group shot, guys taking a snowboarding break in the sunshine at Japan’s majestic Annapuri ski resort.

“ran into little bull (at)bossrbr lets catch up tonite dude” says one friend.

“Snow snow snow” chimes in another.

And then Bossrbr: “Wof wof.”