By Andrew Hamlin

Northwest Asian Weekly

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

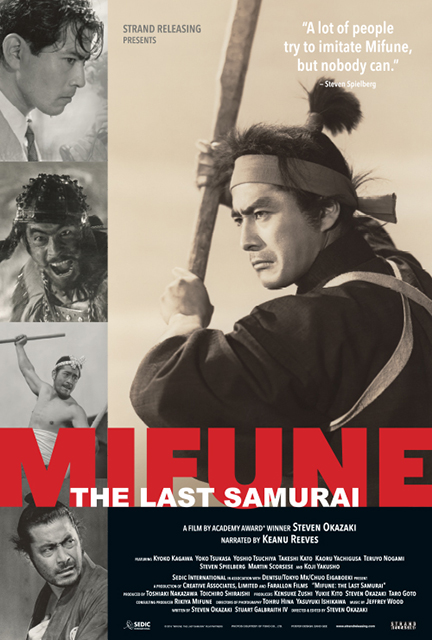

This documentary about Japan’s greatest film actor doesn’t start off with a flourish of praise and clips from the life and work of Toshiro Mifune (1920-1997), legendary for his portrayals of samurai and other madmen. He is known for his incredible collaborations with Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998). It first focuses on a small, old man directing swordfights. Swordfights which seem entirely of the samurai period — costumes, swords, facial hair, ferocity. Until a voice yells in English, “CUT!” and we’re reminded that we’re watching a movie. And for the moment at least, a movie showing the making of a movie.

The old man takes a break and a screen title identifies him as Kanzo Uni, an actor, stunt coordinator, and swordfighter. He was killed by Mifune more than 100 times on-screen.

Uni often works with real swords, and a bandage on one arm silently testifies to the risks of his profession. But he’s hearty, hale, and passionate about the past and present. He has plenty of Mifune stories to share, although most of them involved being slashed, mock-slashed, and/or dumped on the ground.

The mighty Mifune’s been dead for almost 20 years now, and finding people who remember him is becoming harder. Director Steven Okazaki finds some of the crucial players, ranging from Mifune’s co-stars (Yoko Tsukasa, Yosuke Natsuki); to Westerners eager to sing Mifune’s praises (Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, who cast the Japanese star in his own farcical “1941”); Mifune’s own son, Shiro; and a few more colorful, lesser-known folks, notably Haruo Nakajima, who appeared in two of the most important Japanese films of all time, in 1954 — one with Mifune, one without. The one without Mifune was the original “Godzilla,” for which he wore the dragon-lizard’s rubber suit. The one with Mifune was Kurosawa’s “Seven Samurai,” where he appears as a villager.

And for anyone out there who doesn’t already know the movies, I beg of you to go out and watch them.

You’ll find your lives much enriched. “Seven Samurai” stands as the finest band-of-samurai film of all time, near-perfection, and constant exhilaration over more than three hours. “Yojimbo,” from 1961, finds two warring clans in a small town pitted against Mifune, the one-man army. This, then, was the epitome of the lone ronin — a masterless samurai with nothing but his sword, his mind, and his code. Samurai films, called chanbara, had existed since the dawn of Japanese film, and the documentary does its due diligence including film excerpts from the silent era.

Kurosawa kept one foot in the past, but stepped boldly forward with the other one. He had the audacity to conceive of fresh approaches, and the talent to realize them. He drew ideas from the West, and in turn influenced the West. And he had Mifune — gruff, grunting, wild-eyed, and primal — to embody that concept.

The documentary sadly spends little time with Mifune’s non-Kurosawa roles, although he amazed in some of those. It spends even less time on the non-samurai Kurosawa collaborations, although Mifune could burn up the screen as an executive caught up in a kidnapping (“High And Low”), an avarice-loving yakuza (“Drunken Angel”), a detective chasing down his stolen weapon (“Stray Dog”), or even in “Record of a Living Being,” a man consumed with fear and anxiety. A powerless, terror-stricken soul, the very opposite of the Mifune stereotype. But the man displayed many facets.

Family, friends, and co-workers all agree that Mifune could be generous and warm, but he drank heavily, found solace in driving cars very fast, and generally kept a part of himself hidden.

He once said that no one would understand the true Mifune. Because whatever he said, no one would listen. And we’re not even sure what he meant by that. He was the ronin, in his own head. A lone wolf. One can appreciate, even admire, the wolf. But we may never know the wolf.

“Mifune: The Last Samurai” opens Friday, Jan. 6, at the Grand Illusion Cinema, 1403 N.E. 50th Street, Seattle. For prices and showtimes, visitgrandillusioncinema.org.

Andrew can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.