By David B. Williams

The Lake Washington Ship Canal and Hiram M. Chittenden Locks will officially be 100 years old on July 4, 2017. But their story begins on another July 4 in 1854. On that day, Thomas Mercer spoke to a crowd of early Seattle settlers and suggested the name Lake Union for the lake where everyone had gathered. He chose the name because of the possibility “of this little body of water sometime providing a connecting link uniting the larger lake and Puget Sound.”

The Lake Washington Ship Canal and Hiram M. Chittenden Locks will officially be 100 years old on July 4, 2017. But their story begins on another July 4 in 1854. On that day, Thomas Mercer spoke to a crowd of early Seattle settlers and suggested the name Lake Union for the lake where everyone had gathered. He chose the name because of the possibility “of this little body of water sometime providing a connecting link uniting the larger lake and Puget Sound.”

Little was done to make Mercer’s dream a reality until March 1883 when a group of investors led by Thomas Burke and David Denny formed the Lake Washington Improvement Company. On June 6, the Seattle P-I reported that J.J. Cummings and Co. had won the bid to dig the canals. They would employ a hundred men and many teams of horses. Reflecting the growing racism among some in Seattle, Cummings promised that he would not hire any Chinese laborers.

Cummings began work on June 16 and kept a rapid pace by adding more men and teams throughout the summer. In July, his crews removed 14,000 cubic yards of material for a canal connecting the two lakes at the location of the modern SR-520. But then the men ran into hardpan, firmly compacted sediment deposited during the last ice age. When Cummings asked for more money than he had initially bid for sediment removal, the Improvement Company rejected his demand. In October, they abrogated his contract and hired Chinese labor contracting firm Wa Chong.

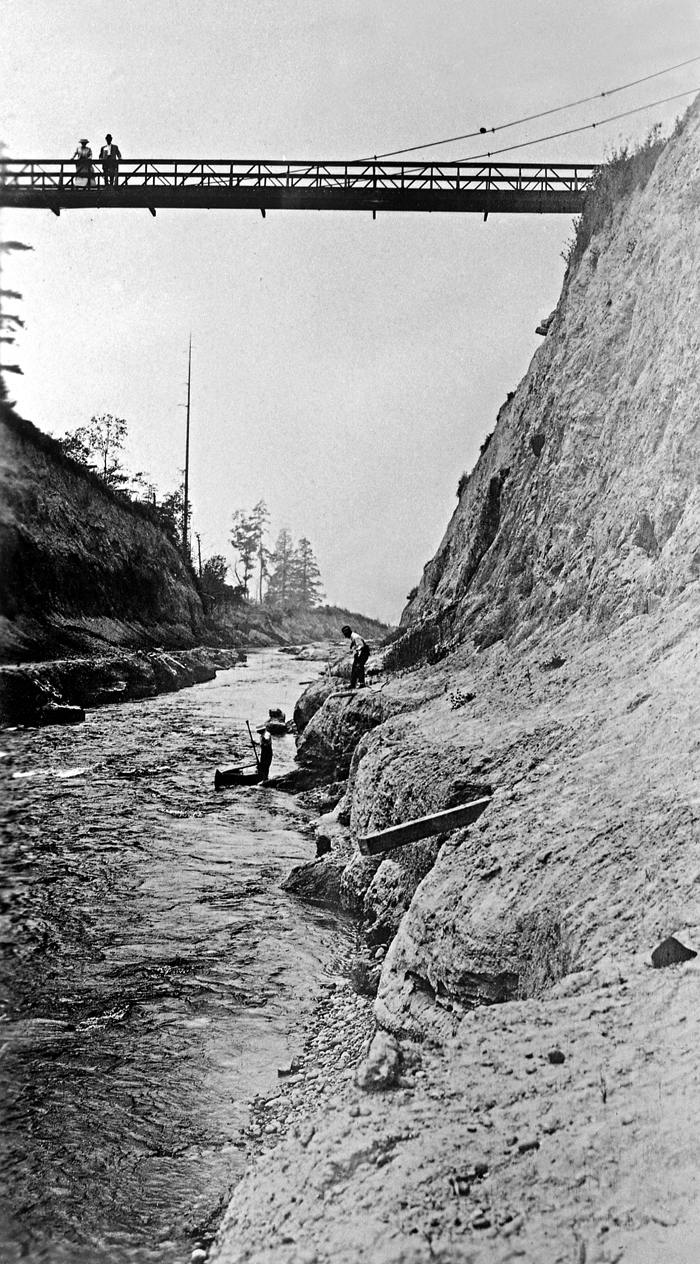

Run by Seattle’s first Chinese resident Chun Ching Hock, the Wa Chong Company provided work crews for numerous manual labor contracts around Seattle. For the canal, they would open a cut three-fourths of a mile long, 10 feet deep, and 20 to 30 feet wide between Lake Union and Salmon Bay.

By March 1884, Wa Chong’s men had advanced from Salmon Bay to within 50 yards of the lake, but were forced to stop work by a court case brought by David Denny’s mill company. He worried that the canal would lower the lake and make the mill inoperable. The only way Wa Chong’s crew could complete the job was to follow the court’s restraining order to build “sufficient locks, gates, or dams” to keep the lake at its “ordinary natural level.”

Beyond these details, what Wa Chong’s men did and when is not clear. All the information that exists comes from later sources. The crews either finished digging in 1885 or 1886. Contemporary accounts describe their work on the canal from Salmon Bay to Lake Union, but there is no first hand evidence as to whether they worked on the Portage between the lakes, even though it makes sense to assume that they did complete the job started by Cummings. The one clue that points to this outcome is a letter written in 1903 by Army Corps Assistant Engineer Eugene Rinsecker, who noted that he remembered seeing Chinese workers using picks and wheelbarrows at the cut, which was wide enough for logs and small vessels.

Although Wa Chong’s canal was eventually supplanted, it was an essential first step in the development of the modern ship canal and locks.

Author David B. Williams is working on a book for HistoryLink.org about the history of the Ship Canal and Locks. He needs help connecting with descendants of the men who worked for Wa Chong on the canal still living in Seattle. David can be reached at wingate@seanet.com.