By Stacy Nguyen

Northwest Asian Weekly

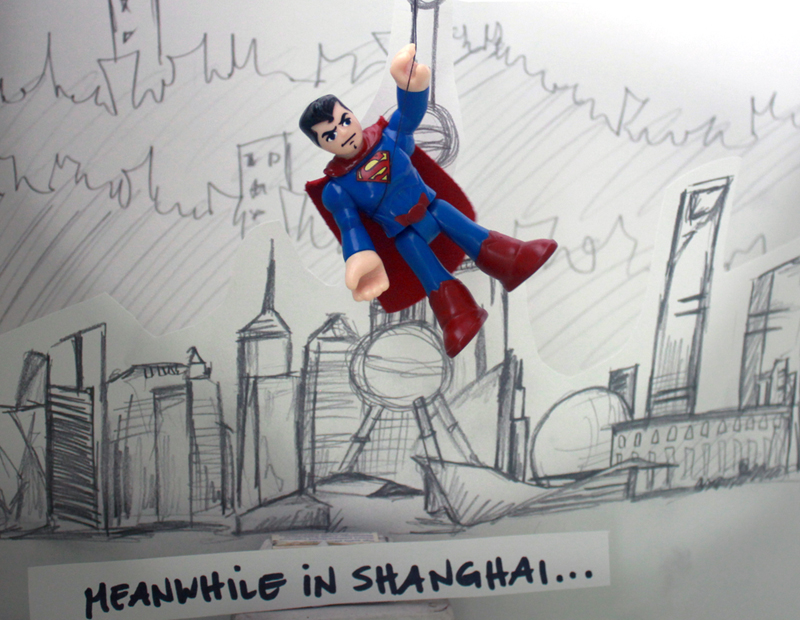

Image by Stacy Nguyen/NWAW

“Superheroes aren’t people,” said Daniel Nguyen, an account manager. “The comics medium makes it very difficult to show them as anything other than a faceless list of attributes. Flight. Strength. Laser eyes. Whatever. And I specifically use the word ‘faceless’ because who knows what Superman looks like? What are Batman’s distinctive facial features? We don’t really know. And every artist has a different interpretation. Plus — most of them wear masks all the time. …”

“This makes the issue of race a slightly tricky one to handle when stories involve giant monsters and alien invasions and whatever,” added Nguyen. “And why is Superman white? He’s supposed to be a goddamn alien.”

A new (non-white) superhero

At WonderCon in Los Angeles during the last weekend in March, DC Comics announced a new addition to its Superman canon. Titled New Super-Man, the series will follow Kenji Kong, a teen who will be infused with super strength, super speed — the things associated with the most famous Clark Kent incarnation — but this Super-Man is Asian and will fight evil-doers in Shanghai.

New Super-Man is being penned by Gene Luen Yang (art is by Victor Bogdanovic). Yang is Chinese American with parents from Taiwan and Hong Kong.

In a 2008 interview at Penn State University on graphic novels, Yang revealed that his mother purchased his first comic book for him when he was in fifth grade. That title was “DC Comics Presents Superman #57.”

Yang graduated from the University of California, Berkeley in 1995 with a degree in computer science. The following year, he self-published his first comic. From the start, his work featured Asian Americans and dealt with issues of race and ethnicity. Notably, in 2007, Yang’s “American Born Chinese” graphic novel won the Michael L. Printz Award for Best Graphic Album: New.

Details on the upcoming New Super-Man title are still sparse — it’s unclear why the character has a Japanese first name and how he fits into the at-times convoluted Superman continuity — but expect some answers on July 13, when “New Super-Man #1” appears on stands.

The birth of an American icon

In 1933, while still in high school, classmates Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster wrote and illustrated a short story starring a villain with psychic powers — a character that had the underpinnings of what would eventually become an icon.

“Superman always felt a bit like he was supposed to be a symbol of American might and goodness,” said Andrea Squires, who is a teacher. “Even if he wasn’t originally created in that vein, he could be and probably has been used that way during wartime.”

In 1938, Superman debuted in “Action Comics #1,” and the response to the series was overwhelmingly positive. At the time, the United States was nearly a decade deep in the Great Depression (Black Tuesday occurred Oct. 29, 1929). In 1939, the world was on the brink of another global war and, in the coming years, the United States would starkly increase its military spending and draft its millions of unemployed young men into war.

Siegel and Shuster have admitted that Superman was derived from wish fulfillment. Superman’s alter-ego Clark Kent is a seemingly normal everyman — who possesses extraordinary powers and uses those powers for the greater good. This kind of optimism touched the imaginations of a generation of young Americans.

Persisting influence

Nguyen’s parents divorced when he was young. His mother worked long hours and Nguyen retreated into the world of superheroes. “They helped inform my ideas of masculinity and manhood,” said Nguyen.

Nguyen watched “Batman: The Animated Series” on Fox (1992), helmed by Bruce Timm and Eric Radomski, written by Paul Dini and others. In 1997, this Batman series was retooled as “The New Batman Adventures” and packaged with “Superman: The Animated Series,” airing as a block on the WB.

“[That] Superman looks vaguely Asian,” said Nguyen. “Bruce Wayne also looks vaguely Asian. Now, I’m not saying that the creators intended for these characters to be Asian. I’m just saying it’s vague enough for young Daniel to be really confused about who these heroes were. Did they represent me? Did they speak for me? Could I just — blur their race and ignore their civilian names? Could they be heroes for me?”

“Well, yes. Of course they could,” said Nguyen. “Because I didn’t have any other options. There were no Asian superheroes. I had no role models who looked like me. This was the closest thing. So I was hooked. I watched every episode. I bought all the toys. I was a weak kid who got picked on. I wasn’t as tall as the other boys. But every day after school, I could hangout with Batman and Superman and Spiderman and the X-Men. They were strong. They beat up the bad guys. The appeal is really that simple. They were powerful. … Only once I grew older and gained some perspective on race did I really become disillusioned about the whiteness of my idols.”

An immigrant story

Just as Superman has been politicized in the past — he was once used to sell war bonds to children — he continues to be used as an allegorical device to this day. It’s been pointed out by many that Clark Kent is the quintessential illegal immigrant — a foundling with no documentation, who has to live a double life hiding his true identity.

Of course, this notion of having dual identities resonates in all immigrants and people of color. Cultural historian Aldo Regalado wrote in his book, “Modernity, Race, and the American Superhero,” that the Superman character pushed the boundaries of immigration acceptance in the United States at the time of his conception, challenging the notion that Anglo-Saxon ancestry was the source of all might.

However, Regalado also has asserted that these stories and characters both affirm and subvert “conventional notions of race, class, gender, and nationalism.”

That is, despite technically being an immigrant, Superman is still a superhuman, white, blue-eyed American male.

Race, gender, ethnicity, sexuality — things that deviate from the traditional white heterosexual male homebase in comic books — can be areas fraught with stereotypes or fetishized.

“[There’s] Shang-Chi (Marvel),” said Nguyen, “who is a minor Asian superhero who took a backseat to Iron Fist — this is stupid because they essentially have the same powers, but Iron Fist is white.”

Nguyen also pointed out that the Mandarin, a major villain for Iron Man, was played by Ben Kingsley, who is of British and Indian descent, in the films. “The Mandarin is essentially Fu Manchu, the ‘Yellow threat’ embodied in a person,” said Nguyen.

“[I’m] a little nervous about how DC will represent Chinese power structures [in New Super-Man] and how it will want to position [Kenji Kong] vis-a-vis those power structures,” said Squires. “And [whether] the U.S. [will] appear as a counterpoint to China — which could be problematic.”

China versus …?

“Well, this [New Super-Man book] sounds interesting, and I’ll definitely check it out,” said Rob Veatch, an artist.

“Don’t know if this will grab enough readers to continue for more than a year or so, but we’ll see. I think the setting being in China gives you more unique cultural territory to explore than you would have if this was a Chinese American dude.”

According to Bloomberg, China is set to overtake the United States in box-office receipts by 2020. In 2014, Chinese movie theaters reportedly brought in $4.8 billion.

With China as a huge customer, Hollywood — and similar media such as comics — have moved away from casting the Chinese as villains. Because it just doesn’t make financial sense to alienate such a significant customer base — one-fifth of the planet.

The 2012 “Red Dawn” remake originally pitted the United States against a Chinese enemy — but thought better of it and changed the threat to North Koreans in post-production.

This light treading is a clear deviation from the anti-Asian rhetoric in popular media mid-century, when racist anti-Japanese and anti-Chinese propaganda was widely used during World War II.

“[Gene Luen Yang] is obviously a bombass Asian American writer, and I’m sure he will do baller things with this [New Super-Man] book,” said Nguyen. “His previous work always handled Asian American identities in interesting, tangible, and relevant ways. I wonder how much creative freedom DC will give him though. … [But] having an Asian writer write an Asian character is obviously the right choice — one that Marvel hasn’t always made in the past.”

“To echo what Daniel [Nguyen] said, who knows how much freedom DC will give [Yang]?” said Squires. “Also I might be reading more into what past Superman iterations mean for this one than I need to, I don’t know. I just have little trust in big American publications when it comes to representing Asian countries with nuance. Hopefully the choice of author will counter this tendency in this case. I do think that broadening canons to make them more reflective of the reality of racial diversity is a good thing — obviously.”

*Daniel Nguyen is not related to Stacy Nguyen, this story’s reporter.

Stacy Nguyen can be reached at stacy@nwasianweekly.com.