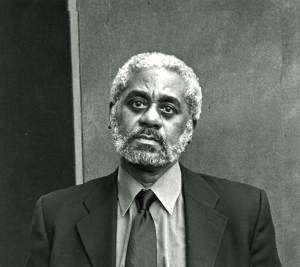

Charles Johnson

By Judy Lightfoot

Crosscut

In an ancient Buddhist parable, an ox runs away from a young herder. Traditionally, a series of ten drawings shows the boy searching everywhere for the beast, eventually finding it and taking charge, then climbing onto its back to ride it home.

Award-winning Seattle author and retired University of Washington professor Charles Johnson told me that story over a pot of tea as we talked about his recently published collection, Taming the Ox: Buddhist Stories and Reflections on Politics, Race, Culture, and Spiritual Practice (Shambhala: 2014). In the parable, he explained, finding and taming one’s ox means working to learn that the separate self is a fiction, a false self.

Between the true self and the world, as between the true self and other persons, no separateness and no boundaries exist. All is One. Which is why the tenth panel shows the boy returning to his village, full of compassion, to help alleviate the suffering of all living beings.

What insight can this Buddhist lesson, and other traditional teachings collectively called the Dharma, bring to racial conflicts currently roiling American society? Does Buddhist practice offer something of value to black people born into the era of what Johnson calls “Jim Crow lite”? Can such practice benefit whites as well?

“Riding Home” is one of the traditional series of ox taming pictures. This one is by 15th century Rinzai Zen monk Shubun of Japan, who is said to have copied 12th century works by a Chinese Zen master. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

According to Johnson’s book, “the historical and present-day suffering experienced by black Americans creates a natural doorway into the Dharma.” It’s just one reason why he believes that Buddhist teachings should be part of conversations about ethics in every community today. Among other things, the author advocates teaching meditation in school, so kids can begin to understand not only math and history but how their minds work. He cites a study of boys in the United Kingdom who learned to use meditation to increase their self-control and their ability to greet experiences, including schoolwork, with calm attention and curiosity. Lifers in an Alabama prison have learned to use meditation to quiet their minds and behave more peacefully, writes Johnson, pointing to the documentary film The Dhamma Brothers.

Racism today may be more subtle than in the past, but it still damages the human spirit and seems to be fueling the deaths of unarmed black males at the hands of police. In a brief, heartbreaking New York Times video, A Conversation about Growing Up Black, boys and young men describe how racism affects them daily in ways large and small. One boy observes that no matter how upright and civil he tries to be, “The way people perceive you, it’s not up to you.” As a result, says another youngster, “We don’t know what freedom is.”

That is, if you’re black, others have you nailed down in their minds the minute you come into view. They think they know about you even though you merely passed them on the street. What would it be like to feel imprisoned for life in a public image of yourself as somehow lacking, inferior, wrong, a threat?

Johnson’s essays in Taming the Ox present Buddhist practice as a path to freedom that is “a matter of life and death to black Americans.” He reminds us of the Dharma teaching that though pain is inevitable, suffering is not: We can choose how to respond to pain, and Buddhist practices help us respond wisely. So although black Americans today aren’t responsible for having formed an unjust society, they’re responsible for how they react to injustice, and developing a felt sense of oneness with others can lead to a peaceable, constructive, even compassionate response.

Whites need liberating, too, writes Johnson. White Americans can use the Dharma to free themselves from the centuries of racial indoctrination that have limited them, closed them off in a blind and false sense of superiority, barred them from knowing black people and treating them with due respect.

Further, Americans from all backgrounds can use the Dharma to stay mindful and at peace amid what Johnson describes as the poisonous divisiveness of our nation’s politics and the shameless blandishments of the marketplace. Instead of battling for power, instead of dealing with feelings of separateness and isolation by shopping, gourmandizing, boozing and mindlessly turning “winners” into heroes, one can use Dharma wisdom to ease suffering in others’ lives and our own.

Our Sponsors

Johnson reminded me that the East has no monopoly on wisdom. “You can find Dharma wisdom in Ben Franklin,” he said, and noted that it was a Baptist leader, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who called our supposedly individual selves “networks of mutuality.”

Indeed, interest in the benefits of meditation is rising in the Western world, as reflected for instance in recent programs broadcast on NPR.

Following the essays collected in the volume are six stories. These mix elements of parable and fabliau with conventions of realistic short fiction; one narrative is recognizably set in Seattle’s Wedgwood neighborhood. The tone is exuberant, and comic even about the practice of Buddhism, as when practitioners get caught in certain situations (a flirtation; professional jealousy) that challenge their spiritual discipline. In one story, “Guinea Pig,” the narrator gains insight into his human self by experiencing it as the self of a dog.

For six years Johnson has been free to prioritize his writing, ever since retiring as Pollock Professor of English from the University of Washington. “When you’re teaching, students have to come first, always,” he said. But even during his busy academic career, major literary prizes, a MacArthur Fellowship and tightly planned days gave him space to write 16 books, including The Oxherding Tale, Dreamer and the National Book Award-winning Middle Passage. This year has already ushered in The Words and Wisdom of Charles Johnson (a year of interviews conducted by E. Ethelbert Miller) and the second in a series of children’s books, The Adventures of Emery Jones, Boy Science Wonder, that Johnson illustrates and co-authors with his daughter Elisheba.

Johnson also continues to practice Buddhism. Still this man, who has steeped himself in the subject and practiced meditation for nearly half a century, told me, “I don’t call myself a Buddhist.” (It’s only logical: how can a person who has no self call himself anything?) “It’s truer to say I’ve done some Dharma” — that he’s studied and tried to live in the light of the teachings.

How does Johnson feel about the future in America for his 3-year-old grandson? “I do think about what awaits him as a young black male here,” he replied. But, “Buddhism teaches that we can’t live in the future and can’t know the future. We have to be present fully in the here-and-now, and I do know right here, right now, I and my wife and daughter can give him all he needs.”

As regards racism in general, progress in reducing it may be slow, said Johnson, but “there is less racism in America today than in my father’s time, and he saw less in the ’60s than in the ’30s.” Still, racism won’t end soon. “It might take us a century or two, and that doesn’t mean it’s going to happen all over the world — between Hutu and Tutsi and rival groups everywhere.”

Meanwhile, he said, “We need to use the tools we have to decrease the separate sense of ego.” (end)

Judy Lightfoot can be reached at judy.lightfoot@crosscut.com.