By Nina Huang

Northwest Asian Weeky

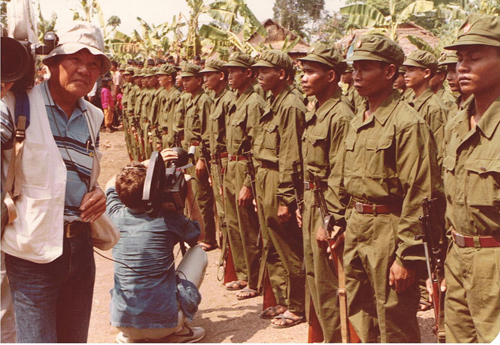

Courtesy movdata.net

Khmer Rouge Takeover

Forty years ago on April 17, Pol Pot led the Khmer Rouge into Phnom Penh and took over with the goal of creating a purely agrarian-based Communist society.

Over a span of four years, the Khmer Rouge government arrested, tortured and eventually executed anyone suspected of being an “enemy.” These included the educated, anyone with connections to the former government, those who were not pure Cambodian and city dwellers who were not deemed fit to perform farming duties.

As a result, the Khmer Rouge takeover remains one of the worst genocides in history. Nearly two million Cambodian lives were lost, and several hundred thousand Cambodians fled their country and became refugees.

40th anniversary

Some of these refugees now live in Washington. According to the 2013 Census Bureau, about 320,000 Cambodians live in the state.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the Khmer Rouge Takeover. Although people may want to forget the genocide and atrocities that took place, several community leaders discuss how important it is to never forget.

Along with 16 Cambodian organizations across the state, Mell is coordinating an all-day commemorative event on August 29 at North Seattle College. The objective of the event is to create a space where Cambodian Americans can embark on a journey of intergenerational and community healing. There will be monks at the event to share blessings at the beginning of the ceremony. Mell hopes that at least 500 Cambodians will attend.

“Not a lot of people want to talk about April 17, it brings up really bad emotions and feelings,” Sameth Mell, minister of culture and information of Rajana Society, said.

Mell said that the Khmer Rouge takeover influenced him generationally. His mother’s side of the family were all executed in front of her.

“The Khmer community has been hyper marginalized within the socioeconomic brackets, we’ve been depoliticized, criminalized, disfranchised, and not only are we traumatized as a country, it was only supposed to be a three-day takeover when they evacuated the country, instead it took four years, there was a whole lot of devastation,” he said.

Mell explained that being an immigrant and refugee was difficult in the U.S. It was hard to find social services back in the 1980s. His family scrambled for resources; and that affected him growing up. That experience made him realize how important it is to reach back to his roots and understand where he comes from.

“I moved to the U.S. when I was 3. I’m a child of that dark period. April 17 is a journey of re-traumatization that the U.S. is continuing to push forth on Cambodia and Khmer political and psychological bodies,” he said.

As a matter of fact, Mell was one out of 30 Khmer Americans who were selected from a pool of 150 applicants to embark on “A Cambodia Journey,” a YMCA-sponsored program that bridges the Cambodian Americans across the nation by taking them on an once in a lifetime trip to Cambodia. The Cambodian Americans will be immersed in the culture with the local communities and work with street kids for two weeks beginning Aug. 23.

Although it’s still a sensitive topic for many, Mell explained that some older folks are starting to step up and talk about the exodus and suffering. They’re starting to share stories of why they left Cambodia as they bridge the gap with the younger generations who are entering the leadership realm in the community.

“We can work together to continue keeping the historical facts alive and not have them become diluted and washed away,” he said.

As a child, Pharin Kong witnessed some of the torture at the camps as well as family members getting sick and dying.

He also moved from camp to camp during the tumultuous times. Kong moved to the U.S. in August 1984 when he was 10 years old.

Kong echoed Mell’s thoughts on the importance of keeping the Cambodian culture alive, and educating the younger generations by bridging the gap and increasing cultural awareness in the communities.

As a community activist and representative of the Cambodian Cultural Alliance of Washington, Kong often works with the older generations to teach them new things as well as make sure they’re caught up to the mainstream culture.

He said that it’s important to remember what happened 40 years ago so that history would not repeat itself. He hopes that the older generations will share their experiences so that the younger people can understand why the takeover happened.

“It’s a story from us (older generation) to tell the next generation that this is what happened, and be able to look forward to the future so the same bad things won’t happen again,” he said.

Kong has been helping with the Cambodian New Year Street Festival taking place on April 25 in White Center.

He hopes the event will bring cultural awareness to other communities so that people understand that there is more to the Cambodian culture and history than the negative aspects like the genocide and Khmer Rouge.

Future generations

Charles Nguyen is a second generation Cambodian-Vietnamese American. His mother spent time living in the camps. She lost five out of 10 people to the genocide.

“Growing up, they didn’t talk much about the events. It’s painful for them to think about, and they don’t want to talk about difficult issues; they just want to move on,” Nguyen said.

As a consequence of the takeover, Nguyen’s family grew up poor and it was difficult.

“I didn’t have positive role models growing up, and I’m the first generation in my family to attend college and medical school,” he said.

Nguyen thinks it’s important for people to commemorate the event and bring it to the attention of the public.

He feels that a lot of Cambodians today don’t recognize what their families went through, and hopefully it’ll motivate others to want to dig deeper. He also hopes it’ll raise issues about the U.S. involvement in Cambodia during the Vietnam War that led to the events that happened afterwards.

Nguyen also said that even though people may not recognize the immediate effects of the genocide, there are a lot of economic consequences today. There is a large percentage of Cambodians that live in lower income neighborhoods where they don’t have access to resources or a good education. He added that Cambodian Americans are often “invisible minorities” because people don’t really talk about them.

“With the educational disparity in Washington, it’s important to recognize the minorities within the minorities. Education is the key to getting out of poverty and creating a better life, not only for you but for your family, it’s important to recognize the value that education can bring,” he said.

Mell, Kong and Nguyen all hope that remembering the takeover will help motivate the younger generations to learn about prevent the horrible past experiences from happening in the future.

“Civic engagement is the umbrella onto everything. We can utilize civic engagement as a tool to bridge these cultural divides,” Mell emphasized. (end)

Nina Huang can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.